Now that the Quad’s Washington Summit is over and Aukus has joined the political lexicon, we can perhaps stop plumbing the media equivalent of the Mariana Trench in Indo-Pacific and let the thought nuclear submarine come to the surface. Once its crew has decompressed, the view is bound to be more prosaic and less Prozac-induced. Indeed, several deep-dived observations would then appear flawed. The following facts need to be kept in mind:

For one, the pack of 8 nuclear submarines, the supposed game-changing opening salvo of Aukus, is unlikely to be operational before 2030.

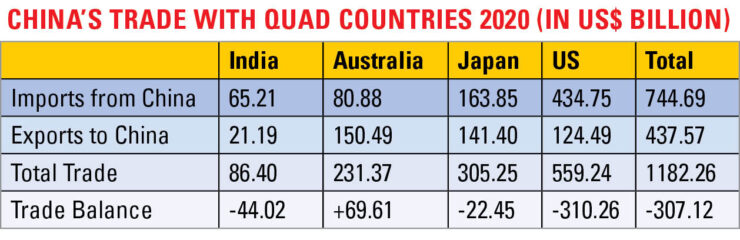

Secondly, the economies of the Quad countries are significantly intertwined with China, making a mutual decoupling between such frenemies is not only going to be difficult but also time-consuming and costly. The table below shows, the total trade between China and the Quad countries is well over 1.18 trillion dollars, with China perhaps being the top trading partner of all the four countries. In addition, the cumulative investments in China by the US, Japan and Australia, three of the Quad countries, stood at (in USD billion) 123.9, 130.3 and 64 respectively. Finally, although most of the 50 million Chinese overseas diaspora is in ASEAN countries, it also has a substantive presence in Quad countries: the US (5.1 million), Australia (1.2 million) and Japan (0.9 million). These People-to-people contacts cannot be ignored.

Thirdly, China has tied up most of its neighbours (notably Russia to ASEAN, Pakistan and Iran) to its apron strings through such devices as BRI, various bilateral and multilateral trade and investment pacts, so isolating it may be impractical.

On other hand, US history is replete with attempts to contain its detractors by universal but unilateral action, from the Monroe Doctrine of 1823 to the ongoing sanctions against Iran. After a protracted Cold War, the dismemberment of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s was seen as the success of its containment policy. However, in this existential pursuit, Washington cosied up to Beijing since 1971 and indulged the latter – from abandoning Taiwan to the UN Security Council’s permanent seat. Beijing’s open and privileged access to the American capital, technology and markets for nearly half a century played no small part in creating a supersized China. This lavishing of China continued for nearly three decades after the Berlin Wall came down. West’s current demonisation of China is blowback on half a century of their fascination with Beijing, often at India’s expense.

A finer point in the US containment strategy is its duality: militarily, a coalition of willing is created, often in tandem with an overlapping regional politico-economic structure to shore up the dominoes. Thus, NATO and the European Community were created almost simultaneously to contain the USSR and Warsaw Pact. Similarly, the Vietnam War led to the ASEAN complementing the ANZUS. Therefore, it is hardly surprising that Aukus and Quad are the latest Avatars of this well-worn strategy to contain China.

However, there are likely to be several systemic complications this time: At the peak of the Cold War, the USSR’s nominal GDP was one-seventh of the US. This time China’s nominal GDP is nearly 60% of the US and China is said to have already overtaken the US GDP in PPP terms. Moreover, the Chinese seem to be preparing for some time for this “mother of all battles” with the US-led coalition. With some conjecture, it is possible to interpret the recent string of geostrategic events – from the Wuhan pandemic to South China Sea territorial grab and from Himalayan scruffle with India last year to the end of term limits for President Xi at the last Party Congress – as pre-emptive actions taken by the Chinese leadership to seize the offensive.

Nevertheless, a new all-out Cold War is not inevitable and the two main protagonists have taken some steps to diffuse the tensions. On September 9, less than a week before Aukus formation, Biden and Xi talked to each other for the first time. Similarly, on the day of the Quad Washington Summit, the US authorised the release of Huawei Technologies owner’s daughter Meng Wanzhou from house arrest in Canada. Moreover, the two sides have also eschewed fire-eating rhetoric at the UN General Assembly’s annual session, even as Chinese leadership has leveraged the growing friction domestically to add a twisted “Wolf-Warrior” narrative to the ongoing centenary celebrations of the Chinese Communist Party.

Semantics apart, a strategic rivalry between China and the US seem to be taking shape, even as its contours are still to emerge. However, in the era of Mutually-Assured Destruction, Supply Chain imperatives and globalisation, it is likely to be differently nuanced. It would be waged less at any killing fields, more at the board rooms, start-ups, trading floors and technical standard-setting sessions. Both sides are prone to miscalculations. The US presumption of technical superiority is as questionable as the Chinese leadership’s overconfidence in their better governance and their belief in the West’s terminal decline.

Where does this escalating drumbeat leave India? We are the only Quad country that shares a land border – over 3000 kms long, non-demarcated and periodically contested – with China. This quasi-adversarial relationship situation is further exacerbated by Beijing’s barely-concealed geopolitical hostility for India, from keeping India away from membership of relevant international organisations to active encouragement to our South Asian neighbours – notably Pakistan, Nepal, Myanmar and Sri Lanka – to move away from us. Lastly, despite recent attempts at correction, our short-to-mid term dependence on China for critical inputs such as APIs, electronics and bulk chemicals, rare earths, etc. weakens our strategic autonomy against that country. All these factors compel us to be more careful as a Quad member.

India faces two specific challenges from China. Firstly, in the military domain, we need to restore greater symmetry to resist Chinese expansionism more effectively. Secondly, our economic growth rate not only needs to catch up with China but overtake it, so as to ensure greater economic convergence with China. While building up our strength, we need to avoid any counterproductive distractions.

The dualism between Quad and Aukus helps us to meet our previously described geo-economic and military challenges. We could leverage our membership of Quad to foster greater eco-technological synergy with the other three members and influence their decision making on other Indo-Pacific issues relevant to us, such as Afghanistan. Cynically speaking, staunching the West’s gravy train to China – and its redirection to us – could make Beijing more reasonable and buy us more time to redress the asymmetry.

Aukus, on the other hand, indicates a growing US resolve to activate its “Pivot to East Asia” strategy. While this is unlikely to be of any direct assistance to us in the Himalayan stand-off with China – it would, nevertheless, raise the cost of military adventurism for Beijing and isolate it regionally. As a “frontline” country, it could also facilitate for India a better access to Western defence technology and intelligence. Moreover, our calibrated pro-activism would also persuade other fence-sitters, such as ASEANs to be more receptive to “a free and open Indo-Pacific, which is also inclusive and resilient.”

The past few weeks witnessed the first Quad Summit and the formation of Aukus, two developments which have redefined India’s region geopolitics. As we dip our toe in the new Indo-Pacific waters, we better bear in mind two ancient prescripts: Chankya’s Mandala Theory and a Chinese saying: “In a crisis, be aware of the danger — but recognize the opportunity.”

–The author is a retired Indian diplomat. He is the President of Eco-Diplomacy and Strategies (www.eco-diplomacy.com), a Delhi-based Consultancy. The views expressed are personal and do not necessarily reflect the views of Raksha Anirveda