The Strategic Partnership (SP) model has been one of the most pioneering recommendations of the Dhirendra Singh Committee, which aimed to create a vibrant defence industrial base within the country. The most distinguishing feature of the SP model was that it would be steered by the private industry, keeping the Defence Public Sectors (DPSUs) out of the ambit.

After the Committee submitted the report to the government in July 2015, most of the recommendations got incorporated in the new Defence Procurement Procedures (DPP) released in March 2016. However, while Chapter VII of the report was being included, it was left blank with the proviso that the content would be notified later.

Admittedly, keeping the DPSUs out of the critical projects was a tough nut to crack, the consensus rationale of ‘creating capacities over and above the ones at DPSUs’ be dammed.

The much-awaited Chapter VII was finally added to the DPP 2016 in March 2017, and as expected, DPSUs found an entry in the game via a very innocuous insertion: “MoD may consider the role of DPSUs at the appropriate stage(s) keeping in view the order book position, capacity and price competitiveness. Cooperative arrangements including the transfer of technology and teaming arrangements between DPSUs with the SP could be envisaged to enable defence related capacities to be developed in the country or for other reasons as decided by MoD”.

The inclusion has been maintained in the new Defence Acquisition Procedures (DAP) 2020, thereby cementing the inclusion of DPSUs in the SP model.

Project 75 (I), initiated by the Indian Navy, aims to build six conventional submarines plans in the country under the SP model as enunciated under DPP 2016.

The project falls under the 30-year submarine building plan, approved in 1999, under which 24 submarines are to be built within the country (18 conventional and six nuclear).

The Request for Expression of Interest (REoI) for project P 75 (I) was issued in June 2019, which was followed by a Request for Proposal (RFP) in July 2021.

The shortlisted SPs are Mazagon Defence Limited (MDL) and L&T Shipyards, with collaborating OEMs being M/s Naval Group-France, M/s TKMS-Germany, M/s JSC ROE-Russia, M/s Daewoo Shipbuilding and Marine Engineering Co Ltd-South Korea and M/s Navantia-Spain.

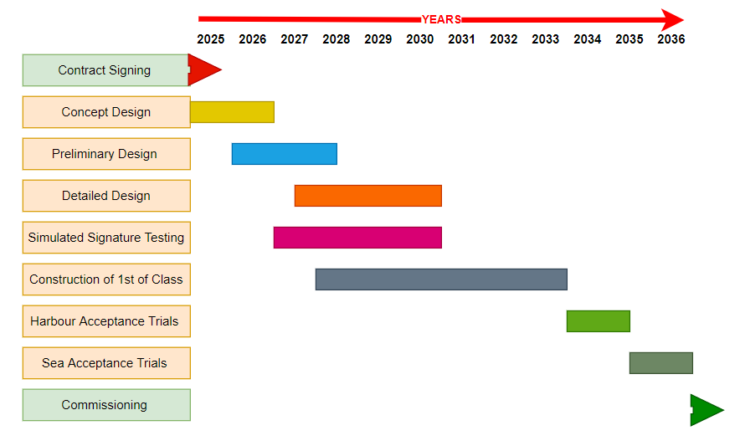

Indian Navy envisages the delivery of the first submarine after eight years from signing the contract and delivery of subsequent submarines at a gap of 12 to 15 months.

So, why is the project going to be a big challenge?

Manufacturing submarines in India with Transfer of Technology (ToT) is not a novel concept. The Indian Navy had attempted projects on similar lines like the Shishumar Class in 1981 and Project 75 or the Scorpene Class in 2005. Both the projects involved ToT and manufacturing in India, albeit with the same shipyard, MDL.

Both the projects got delayed by more than five years. Notwithstanding the multiplicity of causes for the delay, absorption of technology, and the inability to create suitable local manufacturing capabilities were the primary reasons for both the projects. It is apposite that both the projects involved a proven design with almost negligible Buyer Furnished Equipment (BFE) through indigenous sources.

On the other hand, Project 75 (I) calls for OEMs to design a new submarine, based on an existing, proven design, accommodating many BFE via indigenous sources.

While the intentions are welcome, this would require plenitude of hand-holding and know-how, know-why technology and design transfer to Indian partners that will have a direct bearing on the delivery schedule.

Coupled with it is the fact that the political landscape in the country would also churn twice, afflicting the project. A fair assessment of the project factoring various stages and practical issues is depicted in Figure 1. As per the assessment, the earliest the first class (FOC) of P75 (I) will get commissioned is 2036.

The closest example to this project that one can refer to is the French Australian contract (now dropped by Australia, owing to the AUKUS deal) for the Future Submarine Programme.

The agreement envisaged the design and manufacturing of 12 submarines in Australia, with the French DCNS group selected as the partner. Even after taking three years to sign the contract, the project was running behind schedule before it was dropped, with differences in the commercial, engineering and design approaches highlighted as causes of the delay.

The project was almost similar to the SP model enunciated in DPP/DAP. The concern highlighted is that the Australian Navy found it extremely difficult to maintain time and cost deadlines even with a mature Defence Industrial Base (DIB), existing partnership with most defence OEMs and strong project management. With its unpolished and deficient DIB, India would find it extremely challenging to maintain the schedule and indigenous content (IC) commitments.

DPSUs have always remained the holy grail of the Indian defence ecosystem, which few in MoD have dared to tinker with due to the prodigious political and economic ramifications.

Logically speaking, MDL effortlessly fitted into the role of SP for the project. It has the background, project management, design and manufacturing capabilities, adequate space and most of all, a vibrant network of indigenous vendor base; all as a consequence of its earlier submarine projects, one of which (P 75) is still alive.

If L&T wins the bid, it will be a colossal misstep to let all the competencies and expertise go to waste. Therefore, watching how the MoD outmanoeuvres this scenario would be interesting. In addition to the above, since DCNS/NG France has already invested in building capabilities at MDL for the P 75 project, MDL and NG partnership will undoubtedly have a considerable price advantage. To outbid them would require a very competitive bid from L&T, squeezing them further and reducing their manoeuvring space during the project.

REoI stipulates P75 (I) to have Air Independent Propulsion (AIP). AIP is a propulsion technology that allows conventional submarines to operate underwater longer without the need to surface. Since these submarines will be the first to be equipped with this technology in the Indian Navy, it is a critical component of the project and has a direct impact on the design of the submarine.

The REoI also mandates a proven AIP, which going as per media reports, is available with just two of the five OEMs. To muddy the waters further, the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) has been developing an AIP of its own which will be ready for trials shortly. Thus, the AIP for the project presents a unique situation; If SP waits for the DRDO-developed AIP, the design cannot be frozen, and if it factors OEM-provided AIP and freezes the design, going by the past precedence, in most probability, it will be forced to change them to cater for indigenous AIP, whenever the same clear trials.

Whichever way the decision goes, both will have severe impact on the delivery timelines.

Delays in any project are expensive, and in this programme, where many have even questioned the budgeted allocation of INR 42,000 crore, delays would come at a considerable price, almost doubling the initial estimate. An indication of the prudency of the forecast will be available when the commercial bids open, but needless to say, the SP will find it extremely difficult to restrict itself into the allocated budget.

Assessing the project strategically, India would be inducting these submarines from 2036 onwards, more than 16 years after finalising the requirements. 16 years is a massive time gap for any planned capability to be acquired, especially in present times wherein technology development has even defied Moore’s Law.

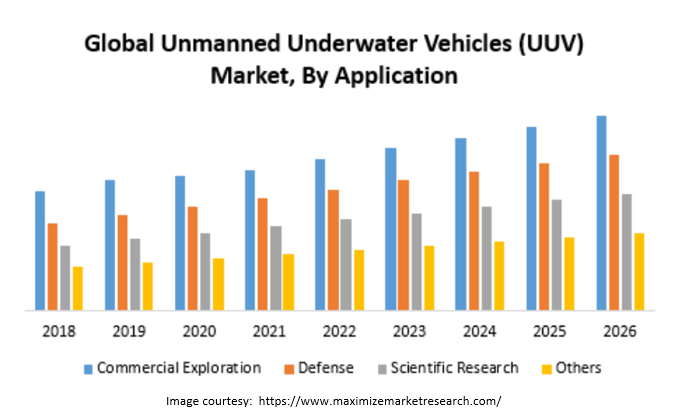

The world’s oceans are getting transparent, and Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs)/Unmanned Underwater Vehicles (UUVs) technology is maturing, impacting submarine operations.

A recent study conducted by the Australian National University, wherein they assessed the impact of future technology on ocean getting transparent, came out with a surprising outcome—Oceans are very likely to become transparent by 2050s.

Towards the study, the technologies (future) assessed included development in system integration, ocean geography, ocean modelling, underwater communication, computer science, new sensors, ocean sensing, autonomous platforms, battery and counter detection.

Almost all modern Navies worldwide are moving ahead on the AUV front, including the Indian Navy. AUVs/UUVs offer is an excellent combination of modularity, flexibility and endurance. In shrinking defence budgets, AUVs offer a way out without compromising operational effectiveness.

While the autonomous component of the UVs, especially the attack-capable, might be a couple of years away, non-attack variants have already started entering service in a few navies, including PLA Navy.

Whether AUVs would replace human-crewed submarines is something yet to be seen, but one thing is for sure, AUVs coupled with future oceans being more or less transparent, will undoubtedly change the way underwater battles are fought, including submarine operations as we know.

P75 (I) project with requirements frozen in 2020, delivered in 2040 and in serve till 2070; how operationally relevant will they be?

If one factors in the above, the SP model itself needs to be re-looked.

Should India invest in the SP model with such long gestation periods? Or should it restrict it to programmes where design to delivery happens in a maximum of five years, like the combat vehicles for the Indian Army?

As one sees, the project path has numerous potholes. Avoiding them and proceeding ahead would be a herculean task for the Indian Navy.

The Empowered Project Committee (EPC) would need to be very careful and establish an effective administration arrangement for the project, ensuring the project goals are met with minimum extensions and within the budget.

The project carries considerable risk, and the EPC has to adopt risk mitigation strategies in advance, at least for issues that it can control. Simultaneously Naval HQ has to be ready to bridge the capability gaps if the project gets delayed incessantly. No matter how the project pans out, one thing is for certain, Indian Navy has a big challenge at hand, most of which it cannot control.

– The writer is voluntarily retired from active service after more than 21 years of commissioned service. He is an alumnus of Naval Academy (first course 10+2 X) and Defense Services Staff College and a specialist in Anti-Submarine Warfare. Presently, he is pursuing PhD in Defense Industrialization and Exports (India) from Indian Institute of Foreign Trade (IIFT). New Delhi. The views expressed are personal and do not necessarily reflect the views of Raksha Anirveda.