It is often said that force level requirements projected by the armed forces reflect a mindset of preparing for the last war rather than the next. However, such an assumption has rarely been borne out by fact and emanates, more often than not, from armchair strategists unfamiliar with the realities of warfare or those with an inadequate knowledge of military matters.

The nature of warfare is constantly evolving because of technological advances and the dynamics of the security environment with neither being mutually exclusive of the other. However, this change is incremental and transitional rather than transformational. Nowhere is this more evident than in the maritime domain.

Naval warfare has evolved over three millennia and from an era when wooden Men-of-War made their way through water with oar-power, we now have submarines and ships being driven by nuclear power. Ironically, in both cases, it is human endurance that is the limiting factor. There have of course been transformational events that have accelerated this change. The Industrial Revolution of the 19th century was one such; the rapid development of technologies during the two world wars was another. The discovery of the power of the atom and its successful harnessing for military applications, which defined the four-decade long Cold War, was another such event and the present-day era of disruptive technologies often referred to as the Industrial Revolution 4.0 may be yet another.

Navies are constantly seeking to optimise their combat capability and are already working towards adapting and integrating autonomous technologies, artificial intelligence, predictive analysis, virtualisation, etc in their existing force structure. However, while these technologies are revolutionising the corporate workspace, their adaptation into military applications and successful deployment in the battlespace requires a more calibrated approach to ensure a seamless integration with existing technologies and an equally seamless transition into the future as legacy equipment and platforms give way to newer ones.

Nature of Maritime Threat

The nature of the maritime threat is also constantly evolving and navies have to adapt themselves to the external as well as internal dynamics shaping the environment. In the last three decades or so, the maritime battlespace has shifted from the open ocean to the littoral and geographically from the Atlantic to the strategic space referred to as the Indo-Pacific. This shift has also led navies to re-think their force structures.

Navies are expensive to build, operate and maintain. Therefore, modern platforms have to be flexible, agile and adaptable to respond to different scenarios. Specialised platforms are now being replaced by multi-role platforms with the flexibility to deploy different specialised payloads for the task at hand. This has been enabled by technology – an example is the increasing use of autonomous solutions to counter the mine threat. Navies are now deploying containerised Mine Counter Measure (MCM) equipment with ROVs and unmanned surface platforms while phasing out traditional minesweepers.

The changing nature of the maritime battlespace is also reflected in the recent trend of disruptive and intimidatory tactics like swarming that are posing a fresh challenge to naval forces. Akin to a person being buzzed by hundreds of bees, it can become extremely difficult for a platform at sea to deliver a well-calibrated response. Similarly, shaping a suitable response to the increase in grey-zone operations, also aimed at intimidating smaller navies and conventional forces, would require a robust command and control network to clear the ambiguity in the mind of a commander at sea faced with such a threat.

While the traditional war fighting role in defence of the nation remains the raison d’etre of navies the world over, maritime forces are also being increasingly called upon to respond to a range of security challenges stretching to the sub-conventional, the non-traditional, the transnational and the hybrid. Each of these requires a different response strategy and it is technology that will provide the flexibility for naval forces to address these multiple challenges without compromising on their core warfighting ability.

The flip side of this availability of cheap and widely available technologies is the narrowing of the asymmetric gap between traditional naval forces and the sub-conventional threat, whether territorial or transnational. Globalisation and an interconnected world have led to trade dependencies that underline the criticality of resilient supply chains. With more than 90% of global commerce transiting over the sea, ensuring the safe and secure passage of over 50,000 ships carrying this trade across the wide global commons requires a coordinated and cooperative approach.

The anti-piracy operations off the coast of Somalia was a good example of a coordinated multinational approach with various task forces operating under different command structures and also some countries choosing to operate independently but part of the overall effort. Such a coordinated approach would enable an economy of effort and optimisation of the resources that navies would expend in countering these challenges.

This would require an inclusive and cooperative regional capacity building for creating suitable security architecture and developing a coordinated response mechanism anchored in comprehensive maritime domain awareness and effective information sharing. The availability of advanced surveillance and communication technologies has enabled wide swaths of the ocean to be monitored through a multidimensional capability from space, the air, the sea (surface and below) and increasingly from the cyberspace domain. When fed into a robust institutionalised information sharing mechanism, many a developing threat can be pre-empted and neutralised. The Indian Ocean Region Information Sharing Centre (IOR –IFC) based near the national capital is a successful example.

Naval Force Structuring

The size and shape of naval force structures is determined equally by the environment and the availability of technology. Discussions at international maritime technology conferences are increasingly focussing their attention on emerging technologies and their frustration at navies not embracing these adequately. These include discussions on the inevitable shift to unmanned and autonomous technologies, artificial intelligence, robotics, taking the man out of the loop etc. Navies on the other hand are adopting a far more cautious and perhaps a conservative approach and are wary about venturing down this path in a hurry.

The case of the aircraft carrier is one such. The successful harnessing of nuclear power for military applications after the Second World War and the advent of nuclear powered submarines led to the perception that aircraft carriers, which had been the standard-bearers of navies in World War 2, were a thing of the past. It was assumed that these ungainly leviathans would not stand a chance against the emerging surveillance technologies, the precision and lethality of modern anti-ship missiles and the proliferation of well-armed submarines lurking beneath the depths, thus making them easy targets in war.

This led to the epitaph of the aircraft carrier being written several times over and continues to be written to this day. However, even seven decades later, the aircraft carrier continues to be the most visible and potent instrument for projecting a nation’s power anywhere in the world in pursuit of a country’s foreign and security policy objectives. The US Navy’s overwhelming supremacy is underpinned by its 11 nuclear powered aircraft carriers, a force that dwarfs the capacity of the rest of the world combined.

As recently as the early 20th century, the PLA Navy, seeking to end the US Navy’s domination of the western Pacific focussed on developing its A2/AD strategy to mitigate its asymmetric disadvantage and deny the sea to its adversary. This included, amongst other things, the deployment of a range of anti-ship missiles with impressive ranges to keep large naval forces at bay. These include the DF-21D and perhaps the DF 26 anti-ship IRBM, euphemistically termed the ‘carrier-killers’, to thwart the US aircraft carrier presence in the South China Sea and off Taiwan.

This re-ignited the simmering debate about the efficacy of aircraft carriers with the so-called pundits wasting little time in sounding its death-knell as a platform totally unsuited for the contemporary maritime battlespace. But lo and behold – soon it was China itself that commenced on an impressive aircraft carrier building programme with an intention of building a 10 aircraft carrier navy (subsequent estimates suggest that it could settle for five within this decade) incorporating the latest technologies, including nuclear power and EMALS.

It is not only the USA and China which continue to invest in aircraft carriers but also the other major maritime powers across the globe. The UK, after a deliberate and prolonged debate over many years finally went ahead with building two 65,000 ton aircraft carriers, the Queen Elizabeth and the Prince of Wales in the last decade. The QE has recently set course for an Indo-Pacific deployment accompanied by its escorts in the UK’s bid to remain relevant in the global power game, which has now shifted east.

In the early 2000s, the UK had been one of the countries to dispense with its modest aircraft carrier fleet in typical political naiveté despite advice to the contrary from the Royal Navy. However, the folly of that soon became evident and should be a call to other navies harbouring similar thoughts. France too continues to deploy its nuclear powered carrier the Charles de Gaulle in the Indo-Pacific to ensure that its flag is prominently visible in an area thousands of miles away from its mainland but where its future sustenance lies with 90% of its EEZ in the waters of the Indo-Pacific. In December 2020, President Emmanuel Macron approved a replacement to be commissioned by the mid-2030s.

Officially, there are currently 21 aircraft carriers operating globally and if one includes helicopter carriers and large LHDs/LPDs that have a sizable aviation component and are equally ‘vulnerable’, the number is an impressive 44. Replacement programmes for ageing carriers as well as new inductions are under discussion in various countries.

The debate about aircraft carriers is alive and well in India too with many of those saying ‘nay’ never having seen one in their lives. Regrettably, even the highest military office in the land has waded into this debate and exhibited a woeful lack of ‘maritime domain awareness’ while ignoring the advice of those who have spent a lifetime there.

This article is not about aircraft carriers but the global carrier acquisition programme is illustrative of the approach to the future maritime battlespace. The current capital being invested in aircraft carriers and large surface combatants, including LHDs, LPDs, destroyers, etc including their future build programmes is proof enough that countries across the world are committed to operating large surface vessels including aircraft carriers for at least the next 50 years. Success in the future maritime battlespace will therefore depend on the ability of navies to seamlessly embrace modern technologies and integrate these into the existing force architecture thus optimising their combat capability and shaping the maritime battlespace to advantage.

In reality, naval platforms of the future, including aircraft carriers, will adapt to the changing milieu in terms of technology and the prevailing environment and accordingly adapt their operational profile while retaining their core capabilities that make them a formidable force at sea.

Do Numbers Matter?

Navies are expensive to build, operate and maintain. Hence the debate about lean force structures with technology being utilised effectively to optimise capability is not unfounded and has merit. However, on the other hand, navies are also about presence and hence quantity too has its own quality. Both China and the US offer good examples. The USA, despite being the undisputed leader in military technology and innovation, is concerned about its depleting naval force levels in view of the impending security challenges. Enhancing its force levels from the existing 285-odd ships to a 355-ship navy is under discussion at the highest levels of government.

China, which has invested heavily in developing cutting-edge technologies in its attempt to narrow the gap with the US, is also building new ships and submarines at an astonishing pace despite already being the largest navy in the world in numerical terms. It is commissioning more than 20-odd major war vessels every year and even surpassed itself when on 24 April 2021 President Xi Jinping commissioned a Type 055 destroyer, a Type 075 LHD and a Type 094 SSBN at Sanya in Hainan on the same day. Never before in post-World War 2 history has any navy added almost 60,000 tons of cutting-edge inventory in a single day!

China is building its navy with a well-defined strategy of achieving global maritime dominance with distinct time-bound milestones. The US Navy too has understood its future force requirement but its programme is dictated by the pulls and pressures of democratic debate though on the issue of China there is broad bi-partisan consensus. Recent war gaming in the Pentagon and other agencies paints a grim picture of the US ability to emerge victorious in a confrontation with China in the western Pacific. Hence, numbers continue to be important. Perhaps there are lessons for India where political indifference and bureaucratic apathy is forcing the Indian Navy to revise its projected numbers downwards every year while it should be doing just the opposite.

The Technology Dimension

While the instruments of naval warfighting may not change much in the years to come, the maritime battlespace of the future will look very different from the present and will be unrecognisable from the past. Ships and submarines are being armed with increasingly lethal anti-ship and land attack missiles that can be fired with pinpoint accuracy on targets deep inside land or far at sea from hundreds of miles away. From subsonic missiles being fired from just beyond visual range, some of which are still in service, naval weaponry has graduated to supersonic and now hypersonic ballistic missiles being fired from halfway across the globe, impervious to any counter-measures and allowing barely any time for a response.

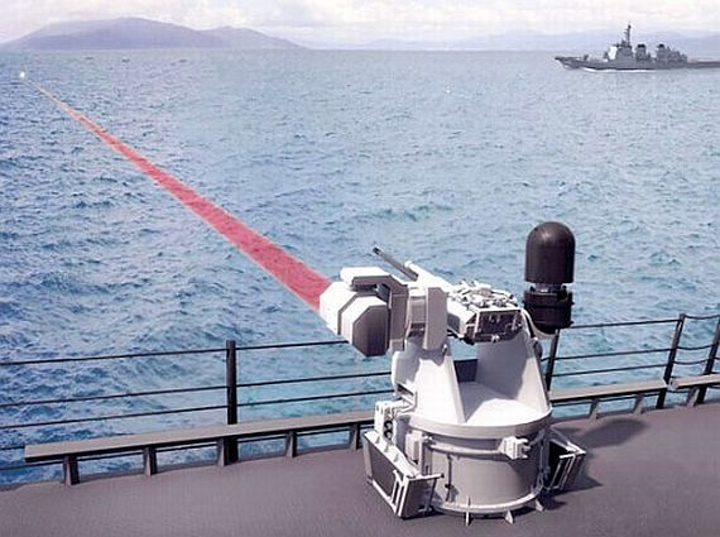

Autonomous technologies in the form of unmanned armed platforms are being increasingly used for ISR as well as delivering effects both from the air, the surface and from below the sea. The militarisation of space and the use of Directed Energy Weapons will also impact the maritime domain. Virtualisation in developing integrated fire control solutions based on the power of computing, use of AI and even innovative technologies like blockchain and 3D printing are being increasingly used to enhance the efficiency of ships and their support organisations leading to a paradigm shift in the way crews think and act on board.

Networked Environment

Navies are operating in an increasingly networked battlespace that goes beyond the maritime dimension and is part of an integrated joint warfighting organisation. No longer are navies operating in isolation on the high seas or submarines operating as lone wolves in fixed patrol areas lying in wait for the enemy. Communications through satellites, the introduction of quantum technologies, improved cyber connectivity and enhanced computing is enabling maritime platforms to share real-time information with each other and the shore through tactical data links and multistatic sensors amongst others and thereby optimising their capabilities towards delivering maximum effect.

The changing nature of the maritime battlespace goes much beyond just numbers, technology or the environment. Navies will find it difficult to cope with the pace of technology and the exponential increase in the speed and capacity of computing because of the complex nature of the maritime battlespace, the wide dispersion of resources and the competing demands within. Navies will also have to contend with obsolescence and support of legacy equipment.

Another challenge will be the ability to successfully adapt and exploit new technology to its full potential in the battlefield before it is superseded by a newer more powerful technology. Navies will therefore have to adapt to the demands of a technologically driven constantly evolving maritime battlespace while adapting modern and innovative technology to the core essentials of naval warfighting and the multiple emerging maritime security challenges in the future.

-The writer is a veteran submariner with over three decades service in the Indian Navy. He is now the Vice President of the Indian Maritime Foundation. The views expressed are personal and do not necessarily reflect the views of Raksha Anirveda