Air Vice Marshal (Retd.) Arjun Subramaniam in his Full Spectrum (India’s Wars : 1972-2020) points out the ‘significant attrition on the Indians’ caused by the 105mm guns and howitzers used by the infiltrators during the 1999 Kargil conflict. He further opines (p 286) that ‘Artillery had a big role to play in the Kargil conflict.’ With the enemy perched atop strategic locations, artillery assault was a pre-requisite to dent the physical and psychological morale of the infiltrators.

Similar argument was posited by historian Kaushik Roy in his ‘From Hydaspes to Kargil’ (p 190):

“….Kargil was also a gunners’ war. The Indian infantry took the aid of heavy artillery firestorms before making assaults, just as the British infantry had asked for the support of heavy artillery…during the First World War.”

However, this module of the need and efficacy of artillery was perhaps for the first time taught in the sub-continent in the Battle of Adyar in 1746. And the lecture was not delivered by the British. It was the French who sermonised.

The Prologue

Seeing the successful business ventures in India of their European counterparts, the French followed suit. In 1664, the French established a company that could trade seriously with India. Jean-Baptiste Colbert, finance minister to Louis XIV, sponsored the establishment of Compagnie des Indes. It was granted exclusive rights to trade with the east for 50 years.

Any losses incurred during the first 10 years of operations would be reimbursed by the government. The state bought 20 per cent of its initial share offering. In 1668, the company set up the first French trading post in India. The first director general of French commerce in India was Francis Caron. He was assisted by an Armenian from Persia – Marcara Avanchinz. Conflict erupted between the two. Such destructive conflicts, writes Roy Moxham (in ‘The Theft of India’) between leading personalities turned out to be a regular feature of the French Indian Company (FIC). Next important development was the construction of the settlement of Pondicherry in 1674 led by Francois Martin.

Pierrre Benolt Dumas, French Governor General at Pondicherry developed good relations with Dost Ali Khan, Nawab Subahdar (Mughal governor) of Carnatic (Karnataka region). In 1739 when Delhi was pillaged by Nader Shah of Persia (Iran), Carnatic was invaded by the Marathas and Dost Ali was killed in battle. Dost Ali’s widow and her entourage were granted shelter by Dumas in Pondicherry fort. Wife and son of Chanda Sahib – Dost Ali’s son-in-law, were also given protection.

The Marathas lay siege on Pondicherry and demanded the handing over of Dost Ali’s family and relatives. Dumas refused. However, instead of taking on the French, the Marathas supposedly backed out. Moxham writes that the Marathas were impressed by the French fortifications of Pondicherry. Moreover, they were gifted 30 bottles of liquor.

In1746, in the backdrop of the Austrian War of Succession in Europe, the French monarch sent a fleet into Indian waters. Already a British fleet had been sent to India in order to exterminate the French trade. The French fleet was commanded by La Bourdonnais. As a counter move, Dupleix and Bourdonnais planned to attack the English at Madras.

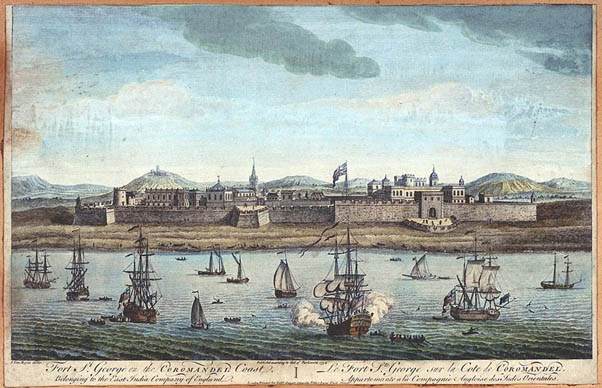

After initial vacillation and argumentation, Bourdonnais attacked Madras with 2,500 men. On May 21, 1746, the British capitulated. Bourdonnais wanted money from the British in lieu of Madras, whereas Dupleix was desirous of permanent ouster of the English company from India. Dupleix prevailed. He intimated the Nawab of Carnatic that the Fort St George (Madras) has been taken by the French on behalf of the Nawab – so the Nawab (Mughal governor) does not get antagonised.

Battle of Madras

However, as Dupleix delayed in handing over Madras to the Nawab, the latter grew suspicious of Dupleix’s intentions. Accordingly, Nawab Anwar-ud-din sent 10,000 soldiers, under the command of his son Mahfuz Khan, to retake Madras from the French. On October 26, 1746, Mahfuz Khan reached at the gates of Madras. He cut-off the water supply to the city. Then, French governor of Madras, Duval d’Espremesnil (son-in-law of Dupleix) felt it necessary to abandon his passive approach of defence, writes Malleson (The Decisive Battles of India).

On November 2, 1746, with 400 soldiers and merely two pieces of field-artillery, the French attacked that portion of Khan’s force, which obstructed the water supply. The rate of fire of the field guns was 5 or 6 times per minute. This outstanding rate of fire bamboozled Mahfuz Khan’s forces. They were accustomed to a single fire in 15 minutes. So, Khan’s forces turned and fled in disorder.

Battle of Adyar

Khan however was not convinced of the military might of the French and wanted to test the volleys of fire himself. He marched to the nearby town of St Thome, in order to intercept the French reinforcement from Pondicherry of 230 Europeans and 700 sepoys being commanded by Louis Paradis.

On the evening of November 3, Khan took up a strong position on the northern bank of the river Adyar, at the very point where the French were supposed to cross the river, and lined up his guns along the bank of the river. But Paradis, who was an engineer by training, and his men started crossing the river undaunted and kept on volley firing at Khan’s forces while crossing.

The Nawab’s forces again got frightened because they were unaccustomed to such a charge from the enemy. They fled and took defensive positions in the fortifications of the town of St Thome. Paradis’ troops kept on firing repeated volleys at Khan’s troops in the narrow street of St Thome. The French soldiers of Madras also joined Paradis’ forces. This time, Mahfuz Khan too, fled. His army followed suit in great confusion.

Eyewitness Ananda Ranga Pillai – dubashi (interpretor) and Dupleix’s secretary – wrote :

“Paradis formed the soldiers and the sepoys into 4 divisions. He ordered each division to engage a separate body of the enemy. He placed himself at the head of the foremost party. Three rockets and four cannons were fired by the Muhammadans. Their contents fell into the river and caused no damage. The French then opened a volley of musketry on the enemy, killing numbers of them.

The Muhammadans threw down their arms and fled, with dishevelled hair and dress. Some fell dead in the act of flight. Mahfuz Khan also ran on foot, until he reached his elephant and then escaped.”

Considering the fact that Pillai worked for Dupleix, his version of the event could very well be coloured. The court historian of Nawab Anwar-ud-din wrote that the French attacked at night and since Khan’s army was not expecting a night attack, they were not ready and hence got confused in the darkness. The court historian’s version too appears biased and as if frantically searching for alibis to defend the cause of ignominious defeat by Mahfuz Khan’s forces.

In this fiasco, barely two French sepoys were killed whereas 300 soldiers of Khan’s army perished. William Dalrymple in his Anarchy writes:

“for the first time, techniques of 18th century European warfare, developed in Prussia had been tried out in India. It was immediately clear that nothing in the Mughal armoury could match their force.

Europeans had long suspected they were superior to the Mughals in tactical prowess, but they had not appreciated how great this advantage had become due to military developments in the half-century since 1687 when the pike-wielding troops of Josiah Child were quickly overwhelmed by Aurangzeb’s Mughal troops….”

“…..widespread introduction of flintlock muskets and socket bayonets which replaced pikes, organisation of infantry into battalions, regiments and brigades made continuous firing by the infantry a possibility.

The standard infantry tactic was a bayonet charge after devastating volley firing supported by mobile and accurate field artillery. The invention of screws for elevating the guns gave artillery greater precision and increased the firepower of the infantry, giving them an edge in battle against the cavalry.”

In this context, it is worthwhile to note that European mercenaries had long been coming to India, because of potential employment as artillery experts. However, many Indian rulers, writes Moxham, especially those who had originated from Persia, had an ambivalent attitude to artillery. They considered it necessary, but unchivalrous – not an occupation for gentlemen. In fact, such an attitude was also prevalent in Europe when small arms and cannons were developed but the Knights would not easily accept them as suitable instruments in battle. Similar conservative approach was seen even during the First World War, when tanks were being introduced to break the deadlock of position warfare, but the then commanders were more prone to clinging to vermin-ridden trenches and lose men, material and time instead.

The Portuguese in India too had this sort of reservation regarding artillery. Hence, though they manufactured artillery, yet their effectivity and accuracy were under the scanner. In fact, the Portuguese employed German gunners and recruited experts from other European nations to manufacture cannons. In 1503, two of Portuguese gun-founders from Milan defected to the Zamorin of Calicut (p 202, ‘The Theft of India’ -Moxham) where they cast artillery and trained gunners.

The Indians on the other hand, were making artillery from before the arrival of the Portuguese, but the quality was below par. Moreover, they lacked the expertise in its effective use. Many Eurasians entered the service of the Mughals. Rumi Khan from Turkey modernised the artillery of Bahadur Shah of Gujarat. He was aided by European mercenaries. Niccolo Manucci was an artillery officer for both Aurangzeb and his brother. Senior artillery officer of Nasir Jung was an Irishman. By the end of the 18th century, European artillery and infantry officers were attached to most Indian armies.

Kaushik Roy writes that ‘Indian armies after the Mughal collapse in the 1740s experienced frequent treacheries’ since the ‘soldiers were more loyal to the jagirdars/mansabdars (feudal lords/Mughal officials) rather than to the crown.’ These private armies of the jagirdars lacked regular sub-divisions and did not have a hierarchical command structure.

Moreover, Roy states that long-term sustained campaigning by the Indian armies was impossible because Indian princes rarely paid their soldiers regularly. For instance, in 1789, the cavalry army of Maratha sardar (leader) Mahadaji Scindia had not been paid for three years. So they refused to fight.

Balasubramanian and Brown inform that:

“The Mughal commander of Ausa (in Maharashtra, India) fort sent a report in 1671 to Aurangzeb requesting him to purchase iron cannon shots using the already sanctioned amount for purchase of stone balls, because he understood the effectiveness of metallic cannon shots.

It may be relevant to point out that the development of cast iron technology in Europe in 16th century permitted large-scale production of cheap cast iron cannon balls…..Unfortunately, Indian rulers did not pay much heed to developing this technology.”

Historian Amar Farooqui in ‘A People’s History of India’ elaborates the role of military technology in European success in colonising the sub-continent. He very correctly mentions the following factors in broad terms for the 17th – 18th century military transformation in Europe:

First, the European armies had gone completely over to fire-arms. Only European cavalry used sabres (swords). Indian horsemen however still continued using bows and arrows.

Second, European horsemen had begun to use pistols in the 17th century itself. For infantry, musket became the main arm in Western Europe by the 16th century. By 1700, the flint-lock had replaced the match-lock for firing the musket.

In the match-lock, the burning end of a rope was made to hit the hole in the priming pan, which in fired the gunpowder charge previously rammed down the barrel. This action then provided momentum to the pellet to come out of the barrel. In the flint-lock on the other hand, writes Farooqui, the trigger made the flint at the end of the arm strike the steel in the pan to let off sparks; thereby igniting the initial explosion within the pan. The flint-lock could work even in wet weather.

Third, at the beginning of the 18th century, the European musket also added the bayonet to it, making it a dangerous weapon for close combat battle as well. The cartridge in European muskets in the 18th century contained the gunpowder charge and the bullet in one packet, which enhanced the frequency of the musket.

Fourth, spread of blast furnaces in Western Europe in the 16th century made possible the manufacture of guns of cast-iron. Whereas in India, the inability to cast iron led to the use of wrought iron, with cannon barrels made of barrel segments joined by thick broad rings – as a result of which cannon pieces were very heavy and difficult to manouvre. Also, Indian cannons took unusually long time to cool and to get reloaded.

Fifth, volley firing by European forces was a tactical improvement in battlefield, due to a well-drilled and properly trained disciplined infantry. Moreover, European armies were regularly paid institutionalised groups, whereas Indian armies were feudal levies.

Military historian Jeremy Black in his ‘War: A Short History’ refers to Michael Roberts’ argument that the innovations in tactics, drill and doctrine by the Dutch and the Swedes (in the 16th century) led to the requirement of more permanent state military forces. In fact, Black mentions Parker’s supposition that the introduction of ‘volley fire’ (one row of soldiers of firing, then reloading whereas the second row then fired to keep the continuity) in the Dutch Army in the 1590s was to transform Western warfare, ensuring that firepower and not manpower would decide the fate of battles.

Everything though was not hunky-dory for the European forces of the mid-18th century. In the words of Jeremy Black (p 18, Introduction to Global Military History, Routledge):

“The problems caused by short-range muskets, which had a low rate of fire and had to re-sighted for each individual shot, were exacerbated by the cumulative impact of poor sights, eccentric bullets, recoil, overheating and misfiring in wet weather. Also, due to lack of grooves in the barrel, the direction of the bullets was uncertain.”

Even with these limitations, European artillery and infantry in mid-18th century wreaked havoc in the military circles in India. Adyar was the finest example and a writing on the wall for future conflicts in India.

-The writer is a PhD specializes on Left Wing Extremism [LWE], insurgency and counterinsurgency, since 2008 and in that capacity has contributed chapters in edited volumes and also been a television commentator. In February 2021, he was invited by the Overseas Security Advisory Council of the US Department of State and the American Chamber of Commerce in Manila to speak on LWE in India and Philippines. In 2020, the New Delhi based think-tank Vivekananda International Foundation inducted him in the nine-member Task Force on LWE. Any opinion expressed is author’s own.