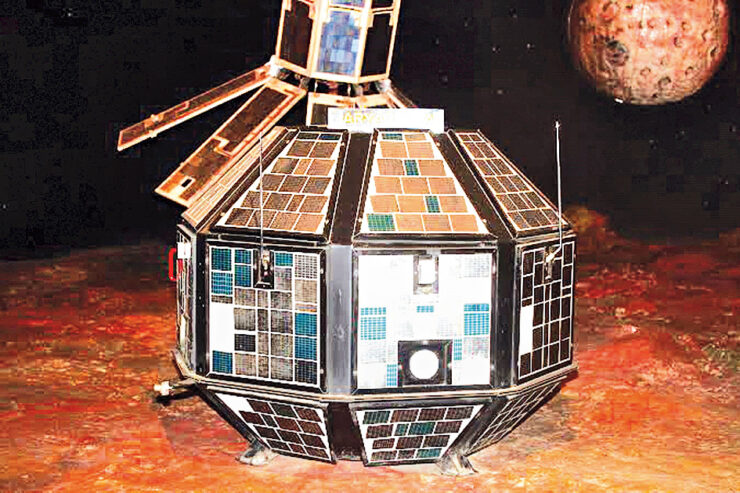

India has carved a place for itself not just in the emerging new world order, much to the angst and annoyance of many established world powers, but also occupies an enviable position in the world space order. The Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), established in 1962, has been exploring space for scientific research, cartography, earth observation, communications and a host of other uses. The initial satellites, Aryabhata and the Rohini series, were considered to be experimental satellites; Aryabhata was the first satellite, launched in April 1975, by the erstwhile USSR, while Rohini was placed in orbit by an indigenous launch vehicle, SLV-3.

The initial Aryabhata and the Rohini series, were followed by the Indian National Satellite System (INSAT) series of multipurpose geo-stationary satellites, built and launched by ISRO. The Indian Remote Sensing (IRS) satellites and Radar Imaging Satellites (RIS) came next. There have been many others, launched for meteorology, ocean monitoring, communication for SAARC region, and for navigation, as an indigenous GPS. ISRO is also working towards manned flight in space, Mission Gaganyaan, (delayed beyond 2022 due to the pandemic) and has plans for building its own space station too. ISRO has not looked back since, and barring a few hiccups, has taken some decisive steps to strengthen its global position, while retaining its lead in South Asia.

These space-based assets are all dual-usage assets. An Integrated Space Cell, under the Headquarters Integrated Defence Staff (IDS), was set up to utilise the country’s space assets for military purposes more effectively, to assess threats to these assets, and plan counter-measures accordingly. Even as the significance of space in national security was understood and acknowledged, India continues to maintain a policy of non-militarisation of outer space, persistently arguing against it in domestic and international forums. The potential use of space assets for enhancing national security, including technology dominance, was always understood by the political leadership, however, the objective was not given any importance, and hence, remained on low priority. Indian space forays, therefore, remained predominantly as a civil space programme, even though IRS satellites did provide inputs to the military. India’s security requirements, hence, were not fulfilled, leading to a gap between India’s space programme and the capabilities of other space-faring nations.

China is a globally-acknowledged space-faring nation, and it is difficult to match its capabilities in the near future; nevertheless, India has made a beginning. Regional and global geo-political situations have steered a change in policy of military use of space by India; the launch of the GSAT-7, also known as INSAT-4F/Rukmini, in 2013, was India’s first dedicated military satellite. Even while maintaining its stance of non-militarisation of space, India appreciated the increasing military role in space-based assets by other space-faring nations. Consequent to this, it showed an increasing partiality to the use of space in other military activities, such as, surveillance or communications, but continued to raise the issue of differentiation between militarisation and weaponisation.

A change in India’s reconsideration of its vehement opposition to space militarisation became visible with the turn of the century; it was first perceptible in India’s reaction to US President George W. Bush’s National Missile Defence (NMD) speech in May 2001, and thereafter in India’s own interest in a Ballistic Missile Defence (BMD) system. India’s strong opposition to non-weaponisation of outer space eased since then, and particularly after the Chinese ASAT test in 2007.

The fast-changing geopolitics, in the region as well as in the world at large, with a display of hard-power, even in space, compelled India to, slowly but surely, modify its stance. Referring to the growing threat to India’s space assets, more so after the Chinese anti-satellite (ASAT) test, and the US destroying its own satellite the following year, the then Defence Minister, A K Antony, announced, on June 10, 2010, the formation of the Integrated Space Cell, under the aegis of HQ IDS, for an effective utilisation of national space assets, as the first step towards an Integrated Space Command! India’s troubled relations with its neighbours, Pakistan and China, could be considered as the main contributory factors that influenced its decision to pursue a military space programme. On March 27, 2019, the government announced that a modified version of the Prithvi Defence Vehicle (PDV), officially named PDVMkII, had been tested against a small satellite; India had joined the elite club of the “Big-3”!

Today, satellites are an essential component for a well-coordinated and synchronised tactical capability, integrating weapons systems and platforms, missiles, radars and sensors, unmanned vehicles, electronics and communications networks, aerial capabilities, logistics and support systems, and defence forces spread across a vast geographical area. With the Revolution in Military Affairs (RMA), advancement in space capability has, thus, become an integral aspect of national security. With the aspirations and development of assets, however, also come challenges and threats.

Satellites and other space systems are extremely technologically-intensive, and hence susceptible to a variety of threats – natural as well as deliberate. While protection against natural phenomena can be minimised through space situational awareness (SSA), deliberate acts, which would include various types of ASAT weapons, co-orbital satellites, directed energy weapons (DEWs), non-kinetic threats, such as jamming, and cyber-attacks, require pre-planned actions through matching technology. The vulnerability of ground systems is being addressed through a variety of steps, especially strict cyber-security measures, it is the threat to the space assets that are a worry, more so after China’s ASAT test and the “satellite-grabbing” demonstration early this year in January.

A military threat is the sum total of capability, capacity and intent. While the capabilities of China, India’s ‘friendly’ neighbour in the North, are well known, Pakistan survives on China’s assistance in space-based surveillance, and communications. Considering the present geopolitical situation in the area, China can, at best, be expected to use its capabilities in the cyber domain, and/or interference in ground-satellite communications; Pakistan, on the other hand, has neither the capacity nor the capability to be of any consequence to India.

India has well-demonstrated its acumen through a fairly successful military space journey, despite a late start and budgetary constraints. Challenges, however, continue to exist, and grow, as the country seeks to increase its presence in space, not just in the military domain, but also for civil uses. The capacities and capabilities are, however, insufficient, to meet the emerging needs.

China continues to show its prowess in space through ASAT weapons and counter-space technologies. The balance-of-power equation is tilted against India, resulting in the odds against it, in the event of a conflict. The immediate need is, hence, to enhance capabilities and capacities.

A renewed and pro-active national space policy is, therefore, the need of the hour. This has to be followed by a much greater involvement, than the present, by the Armed Forces, which should also include the para-military. Conventional and nuclear deterrence can be greatly complemented through the enhanced use of space power. As India has realised, albeit a little late, the importance of utilisation of space in both the civil and military domains, it needs to work towards a clearer and definite space programme. A distinction between the civil and military needs, should be made and prioritised and converted into firm policy structures, as the next step.

Outer Space is no longer just for lullabies for children; it has changed, and so should our efforts!

–The writer is an IAF veteran. The views expressed are personal and do not necessarily reflect the views of Raksha Anirveda