The global powerplay and geopolitical flux are creating strategic security fragility at an unprecedented scale, from the Indo-Pacific to the trans-Atlantic. For India, China’s Himalayan forays and the Russia-Ukraine war have brought their fallouts and lessons. India’s inclusive growth faces challenges of balancing the trio of US-Russia-China; turbulence of the immediate neighbourhood, which has its strategic security dynamics. Both on the western and northern fronts, we face adversaries who have a revisionist and expansionist orientation and a history of backstabbing. The internal security front too continues to have its fault lines challenged and exploited by forces inimical to the national interest.

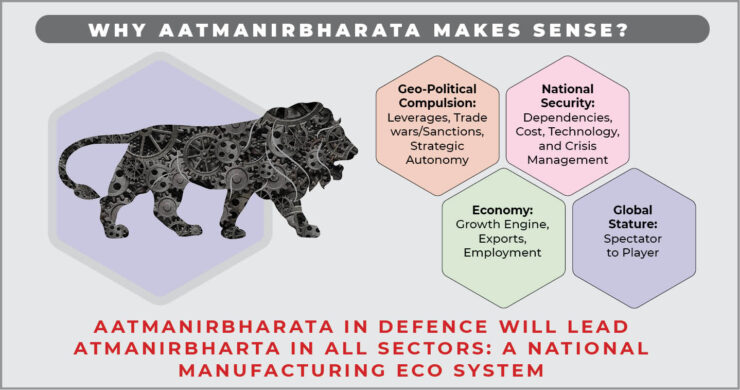

These multi-domain threats have highlighted three key challenges to national security – one the nation will have to fight its battles alone, two, the imperative of indigenous solutions to warfighting, and three, the need to pay heed to Chanakya’s four threat model to a nation – external threat externally abetted, external threat internally abetted, internal threat externally abetted, and the internal threat internally abetted. Thus, a modern military must be based on the foundation of self-reliance and self-sufficiency. Aatmanirbharta is not only a strategic necessity to prevent being a victim of leverage, dependencies, trade wars, and sanctions but also an economic engine of growth, employment, and a symbol of strategic autonomy for the global stature of a nation.

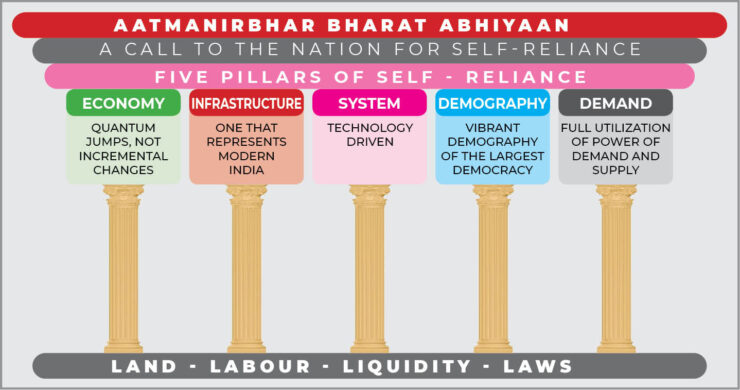

The five pillars of self-reliance remain – an economy which creates quantum change, state-of-the-art infrastructure, a technology-driven system, vibrant human capital (demography), and optimisation of demand-supply potential. The focus accordingly must remain on land, labour, liquidity, and laws. The transformation to be sustainable must address all three critical components; transformed integrated culture, transformed planning process and policies, and transformed planning and execution structures.

Reality Check

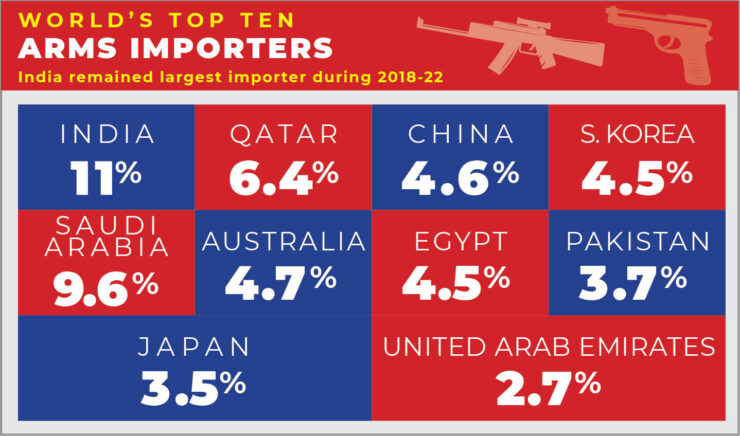

As a nation with the fastest-growing economy, rich human capital, one of the largest defence forces, rich mineral resources, and evolving private defence industry, India possesses the potential of not only being Aatmanirbhar but also a global export powerhouse. However, the glaring gap between “potential and performance” exists and needs to be bridged with a rejuvenated pace both qualitatively and quantitatively for the realisation of its true capabilities. Ironically, India has remained still the world’s top importer of weaponry in 2022, despite a sizeable decline in import burden over the last five years and dispersed dependency.

India’s defence exports have peaked at an all-time high of Rs 15,918 crore in the current financial year, over a 10-times increase since 2016-17 and exporting now to over 85 countries. Yet according to the SIPRI March 2023 report, India was not among the top 25 countries in arms exports, as the year-on-year change (%) fell from 52% to 24%, over the preceding year. This poses challenges to the country’s aim to achieve an annual export target of Rs 35,000 crore by 2025.

The value of India’s defence production has crossed the Rs 1 lakh crore mark in the financial year 2022–23, as compared to Rs 95,000 crore in 2021–22. Domestic procurement climbed to 68% in FY22. The FY24 target is 75%. Yet there are no Indian defence manufacturing companies figuring in the top forty global defence companies, which figures companies of several smaller nations. Ironically despite the number of steps to encourage local manufacturing, procurement, and private sector participation in the defence sector, public-sector enterprises continue to dominate the defence landscape.

India is ranked 40th position out of 132 in the Global Innovation Index 2022 rankings as against 81st in 2015. India has rejoined Kearney’s foreign direct investment (FDI) confidence index list in the 16th position, and the 2nd position in emerging markets signalling a renewed interest from foreign investors in the Indian markets. Despite the global slowdown in overall FDI investments, India remains an attractive and investor-friendly destination that has resulted in the increasing trend of Defence FDI inflows into the country over the last eight years. The government has initiated several policy reforms in the past few years to encourage indigenous design, development, and manufacture of defence equipment, thereby promoting self-reliance in defence manufacturing & technology in the country. Yet the Indian defence industry’s import-export ratio remains inferior to countries with a much smaller defence industrial base.

The Window of Opportunity

Every global security crisis creates opportunities and provides lessons. The US defence industry became the world’s number one during World War II, creating an industry that was worth several trillion dollars in a few decades. Russia-Ukraine war, recent challenges on borders and the desire to indigenise have created a similar opportunity for India.

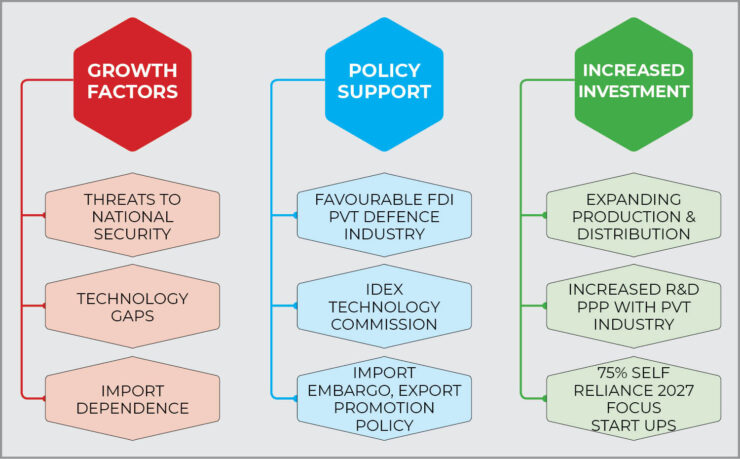

The global defence market has grown at 8.2% CAGR over the preceding year providing an opportunity for Indian exports. Already, 12,000 MSMEs operate in India’s defence sector; they are now being handheld by the bigger defence houses. Ironically, despite a technology development fund and iDEX platforms, India spends less than 1% of its GDP on R&D and a meagre 7% of its overall defence budget, which is way below the global average. The focus must be towards private sector R&D and building a more competitive R&D ecosystem by focusing on emerging technologies to achieve self-reliance in defence. The figure below defines the macro issues of being self-reliant.

Over the past few years, India has initiated several policy reforms to promote defence self-reliance. Make in India, the new flagship program of the Government of India has put a renewed emphasis on creating a conducive policy environment for improving domestic defence manufacturing. These initiatives present opportunities for foreign companies to enter India and local companies to collaborate, design, develop, and showcase their engineering strength. This will also promote India’s objective to create jobs, catalyze technology development, and transform India into a self-reliant nation with export capabilities in the defence sector. India’s existing wealth of talent, technology, and cost advantages together can help make defence products globally competitive.

Bridging the Potential-Performance Gap

The reality remains after every security crisis, there is an emergency procurement impetus for meeting operational deficiencies through off-the-shelf foreign procurements. Thus, the strategic gap between desirability and reality to building Aatmanirbhar defence capabilities though certainly narrowing remains a strategic challenge that requires a pragmatic and holistic, dispassionate introspection at the national level. Operational effectiveness, which is a major outcome of modernization strategy, is based on empowering the warfighter with the best possible means for victory at least cost to lives and in minimum time – Swadeshi (indigenous) or Videshi (imported) in the order of preference. The desirability certainly remains winning Indian wars with Indian equipment, which remains the hallmark of a self-reliant nation.

Some areas require a pragmatic review and thus need to be addressed.

Budgetary Support and Concept of Reservation: A progressive budgetary enhancement to 2-2.5% of GDP is the driver along with the capacity to efficiently utilize it. Reforms for a Capital Revolving Non-Lapsable Fund for new schemes are mandated. Separate budget provision for ‘domestic capital procurement’ needs to be followed up by a roll-on appendage.

Risk Sharing Gain Sharing: A risk-sharing gain-sharing product financing formulation between the government and the defence industry is desirable. “Make 1” in the Defence Procurement Procedure (DPP) was a good example but did not see the light of the day in terms of outcome and financial support by the government. No industry will invest heavily in joint ventures (JVs) or R&D for ‘big-ticket procurements’ unless there are some assurances of it evolving into reality. The Strategic Partnership model also requires impetus to ensure effective collaboration and sharing of risks and rewards between the private sector and the government.

Homegrown R&D: The primary driver must be indigenous R&D. It must be encouraged and, if required, enforced in terms of hardware, software, skinware, and financial allocation in critical areas like raw grade metallurgy, strategic critical electronics, system design, and manufacturing technologies. Augmenting and institutionalizing Defence R&D from the present 7% of the Defence Budget to 10-15% will strengthen India’s capabilities to develop cutting-edge technologies domestically.

Indigenisation and Indigenous Production: Indigenisation must foster indigenous production, and indigenous products must have a very high indigenous content, including all identified critical technologies with Intellectual Property Rights (IPR). Addressing the current lack of a clear mechanism and neutral agency for quantified objective calculation of indigenous content and costing is crucial to incentivize domestic production and ensure transparency.

Import Substitution and Indigenous Content: While encouraging Indian Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) to produce defence items is vital, it is essential to recognise that some import content may still be present in these items initially. However, this import substitution must be followed up by a progressive reduction of the import component. It is essential to clearly define and verify the level of indigenous content (cost, subassemblies, design, and raw material) by an independent verification agency, including IPR holding (both foreground and background), to ensure authenticity.

Collaborative Approach: The need is for an integrated defence ecosystem and a vibrant defence industrial base. Encouraging the integration of Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs), particularly new start-ups, is critical to building a robust and competitive industry. The private sector must be provided a level playing field to promote innovation and competitiveness. When feasible, Transfer of Technology (Tots) available with Public Sector Undertakings (PSUs) should be transferred free of cost to private sector manufacturers, fostering knowledge-sharing and growth. Handholding by the Government, especially for MSMEs, is imperative to nurture their growth and sustainability.

Pragmatic Business Model: Proposals for defence procurement must make good business sense in terms of minimum assured quality and continuity of orders for future requirements to establish a sustainable business model. The unpredictability and uncertainty of commitments, policy changes, and frequent proposal revisions act as inhibitors and must be addressed for a smoother procurement process.

Technology Mapping and Price Indexing: Institutionalisation of technology mapping and price indexing is crucial to ensure coherence and transparency in the Quality-cum-Cost Based Selection (QCBS) model. This will aid in making informed decisions about technology choices and pricing in defence acquisitions.

Encourage Export to International Markets: Success in exports enables the scaling up of production and achieves economies of scale for the entire defence manufacturing ecosystem. Additionally, defence exports provide military and diplomatic leverage and serve as an essential source of revenue generation to support internal requirements. This leverage is vital for an emerging power like India to retain its edge in its strategic sphere of influence and establish itself as a significant player in the global defence market.

Final Thoughts

India faces numerous challenges in transforming its defence industry from Videshi (foreign-dependent) to Swadeshi (self-reliant). The normal rules of market economics do not fully apply in the defence sector, and the existing budgetary constraints and complexities make achieving ideal objectives of quality, quantity, cost, and timeframes a formidable task. Balancing the three key aspects of R&D, technological absorption, and quality control remains a challenge. India cannot afford to be among the top importers of weapon systems when the capability and expertise exist within its vibrant private sector. Addressing these challenges requires pragmatic and focused stimuli, as well as assurances, to bridge the confidence and trust deficit gap. With concerted efforts, strategic partnerships, and a sustained focus on indigenous development, India can move towards a self-reliant defence sector, capable of fulfilling its national security needs and competing globally as a significant player in the defence industry.

-The writer is a defence veteran, a recipient of PVSM, AVSM, and VSM. The views expressed are of the writer and do not necessarily reflect the views of Raksha Anirveda