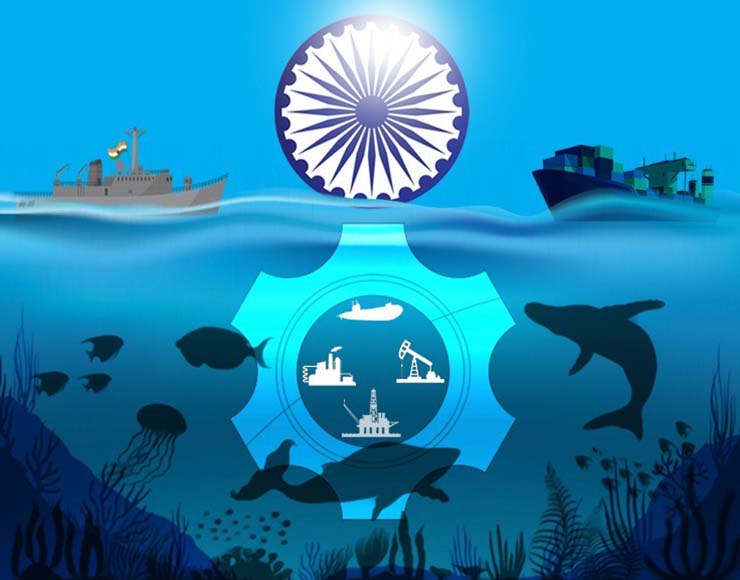

“To me the Blue Chakra or wheel in India’s national flag represents the potential of the Blue Revolution or Ocean Economy. That is how central the ocean economy is to us”

Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Mauritius 2015

As India celebrates 75 years of its independence from the yoke of colonial rule with the Azadi ka Amrit Mahotsav, it finds itself at an inflexion point. Poised on the cusp of transforming into a mature 21st century nation seeking its legitimate position on the global stage, India must fulfil its tryst with its destiny now. That destiny is inextricably linked to the sea in a predominantly maritime emerging world order. It was during his visit to Mauritius in 2015, that the Prime Minister outlined his vision of SAGAR (Security and Growth for All in the Region). SAGAR is an inclusive regional capacity-building doctrine that is now shaping India’s engagement through numerous formal and informal mechanisms with other countries in the region. The building of an effective Blue Economy framework will be central to this.

India, with its peninsular conformation and its strategic location straddling the Indian Ocean almost at its centre, is essentially, a maritime nation. It has a coastline extending 7516 kilometres and depends on the sea for its energy requirements (over 80% of which is seaborne) and its economic well-being (more than 90% of its trade by volume and 74% by value transits over the sea). The future of the nation is firmly anchored in the maritime domain. Over 200 million Indians residing in the nine coastal states and four coastal Union territories are dependent on the sea, directly or indirectly, for their lives and livelihood.

The Andaman and Nicobar Islands on the country’s eastern seaboard, and the Lakshadweep group of islands on the western seaboard, are two strategically located island territories. In addition to being invaluable strategic security outposts, they also nurture a delicate marine ecosystem that is a valuable economic resource. This dependence on the sea is not restricted only to India. It is likely to be the single largest resource sustaining mankind in the future.

The ocean economy is now being increasingly referred to as the Blue Economy. Gunther Pauli coined this term in 2010 when he titled his book “Blue Economy: 10 Years, 100 Innovations, 100 Million Jobs”. However, it was not specifically related to the maritime dimension of developing a sustainable development model. Over the years, the word blue came to be associated with water and led to the Blue Economy becoming synonymous with the maritime environment. The Blue Economy has been defined in various ways, but perhaps the most widely used one currently is the World Bank definition of 2017. According to the definition, it is “the sustainable use of ocean resources for economic growth, improved livelihoods and jobs, while preserving the health of the ocean ecosystem”.

In India, a 2020 draft policy document drafted by the Prime Minister’s Economic Advisory Council titled “India’s Blue Economy: A Draft Policy Framework” gave its own definition of the Blue Economy. “A subset of the national economy comprising of the entire system of ocean resources and man-made economic infrastructure in marine, maritime and the onshore coastal zones within India’s legal jurisdiction, which aid in the production of goods and services and have clear linkages with economic growth, environmental sustainability and national sovereignty.” Developing a Blue Economy has been identified as the sixth of the ten core dimensions of growth outlined in the Government of India’s ‘Vision of New India by 2030’.

In 2014, soon after coming to office, the present government focussed its attention on the maritime sector. In 2015, it launched the ‘Sagarmala’ programme. This is a 9 lakh crore rupee port development-led initiative to transform India’s maritime sector and enhance its contribution to national growth over 20 years (2015-2035). Sagarmala includes a total of 577 projects related to port modernisation (245 projects), connectivity enhancement (210), port-linked industrialisation (57), and coastal community development (65). The programme is regularly monitored and is a work in progress. In 2021, the Prime Minister also released the ‘Maritime Vision 2030’. It is an ambitious plan that includes part of the Sagarmala initiatives and highlights other aspects of harnessing the country’s maritime potential in a sustainable manner.

The aforementioned Draft Policy document promulgated in September 2020, which is likely to be finalised soon, includes the following seven priority areas:-

(a) National Accounting Framework for Blue Economy and Ocean Governance

(b) Coastal Marine Spatial Planning and Tourism

(c) Marine Fisheries, Aquaculture and Fish Processing.

(d) Manufacturing, Emerging industries, Trade, Technology, Services and Skill Development

(e) Logistics, Infrastructure and Shipping (including trans-shipment)

(f) Coastal and Deep-Sea Mining and Offshore Energy

(g) Security, Strategic Dimension and International Engagement

All these initiatives notwithstanding, India still lacks a cohesive all-of-government approach to its maritime sector. A plethora of ministries and departments are associated with this sector, be it fisheries, energy, security, earth sciences, shipbuilding and ship repair, defence etc., with each having different priorities. Hence, there is no single centralised and adequately empowered authority in the country tasked with coordinating the activities in the maritime sector towards a coherent whole. Perhaps, the recent appointment of a National Maritime Security Coordinator (NMSC) may address this shortcoming to some extent. In fact, the NMSC should be given this mandate since the changing nature of the maritime threat with traditional and non-traditional challenges directly impacts the Blue Economy. In India’s case, the Blue Economy is essential to our maritime strategy. It is also a significant determinant in the country’s maritime security architecture. India’s food security, energy security, diplomatic outreach, geopolitical influence and trade and economic strength will be dependent on its ability to harness the seas.

However, not only in India but also in other parts of the world, there is a view that the Blue Economy is not getting the attention it deserves. This is because its linkage to climate change puts it under the purview of environmental organisations. These are not necessarily related to the maritime domain. This causes a lack of understanding of the criticality of the Blue Economy. In India too, the forthcoming Blue Economy Policy is being driven by the Ministry of Earth Sciences, which may not be the best idea.

Since climate change is the single greatest existential threat to mankind, perhaps the environmentalists and those dealing with earth sciences have a point. Over the years, its effects have crept up on us to an extent where it is now noticeably manifesting in our daily lives. We are witnessing changes to the weather pattern, rise in global temperatures, increase in greenhouse gases, melting of glaciers at the polar ice cap, increasing frequency of natural disasters etc. The rise in sea levels, acidification of the seas and the migration of fish to cooler climes directly impact livelihoods and human existence.

With the seas covering 70% of the earth and being the absorber of the Earth’s gases, the marine domain will be a critical factor. This means it, therefore, requires specialised marine expertise to address this challenge. The seas cannot escape the ravages of climate change. Yet, it is also the seas that offer hope for the future. This is subject to humankind developing a sustainable development model for utilising the maritime domain. We should also not allow short-term gains to fritter away this asset in its insatiable demand for resources for a better life.

India is a leading Indian Ocean power dependent on the maritime domain for its security and economic well-being. India has been at the forefront of supporting global initiatives to combat climate change. It has led the International Solar Alliance and is firmly committed to achieving the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) that member nations agreed on at the Paris Conference on Climate Change in 2015 (COP 2015). Of these, it is SDG 14 that refers to ‘Life Below Water’. It states: “Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development”. The SDG has listed 10 targets that nations should achieve over various periods. However, alleviating the effects of climate change on the oceans is not restricted to just these targets. Many of the 169 targets set for the 17 SDGs also impact the maritime domain.

Prime Minister Modi’s SAGAR doctrine envisions a leadership role for India in developing a secure maritime neighbourhood. It hopes to take other countries in the region along, with an inclusive and cooperative multi-sectoral capacity-building approach. SAGAR encompasses much more than just military security. The activities related to SAGAR also address the non-traditional challenges that are of concern, which undermine the Blue Economy initiatives in the region.

The challenges of climate change that pose an existential threat to coastal communities all across the Indian Ocean littoral and threaten many small island states with inundation is the unchecked depredation of marine resources by intra-regional and extra-regional agencies that are destroying the marine habitat. The intra-regional challenge emanates from a host of factors – lack of awareness, a governance deficit, lack of a regulatory framework, economic deprivation etc. The external challenge is from countries like China that pay little heed to international norms and conventions in pursuit of their national interests and use intimidation and illegal practices (including dark ship tactics to evade AIS identification) while destroying the delicate marine habitat. China, in fact, has made deep inroads into the Indian Ocean through its Belt and Road Initiative and is developing a marine infrastructure in many countries with little regard for environmental concerns. China is also the worst perpetrator of Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) Fishing with its massive fishing fleets going about their illegal business unchecked. IUU fishing is considered the biggest threat to a sustainable maritime economy with a rapid depletion in global fish stocks.

The Blue Economy presents India with an ocean of opportunities as it is blessed with favourable maritime geography. Its size and location give it a strategic advantage to ensure its pre-eminence as an Indian Ocean power. It has a resource-rich Exclusive Economic Zone of over 2 million sq. km. which remains largely untapped and unexplored. It has exclusive seabed mining rights in the central Indian Ocean region, which is rich in polymetallic nodules. It has taken various initiatives to ensure the security of its maritime interests in the region through various capacity-building initiatives. India is focussing its attention on creating a resilient and cohesive Indian Ocean architecture. It is attempting to direct global attention towards reducing the region’s vulnerability to climate change and its dangers. To achieve these goals, the government has launched various initiatives like the International Solar Alliance and the Indo-Pacific Oceans Initiative (IPOI). It is re-energising regional multilateral mechanisms like the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) and BIMSTEC to holistically address security and connectivity and share best practices toward enhancing the Blue Economy.

India’s diplomatic outreach over the last few years has led to much greater engagement in the maritime domain than ever. However, internal vulnerabilities remain. The lack of a definite national maritime strategy to develop the country as a maritime power (not to be confused with naval power), a distinct lack of understanding of maritime governance, and the inability to translate vision into reality have been impediments so far. Perhaps, the celebration of Azadi ka Amrit Mahotsav will also lead to a renewed effort at harnessing India’s marine potential and effecting a transformation of the country into a robust Blue Economy and fulfilling its tryst with its maritime destiny.

– The writer is Vice-President, Indian Maritime Foundation. The views expressed are personal and do not necessarily reflect the views of Raksha Anirveda