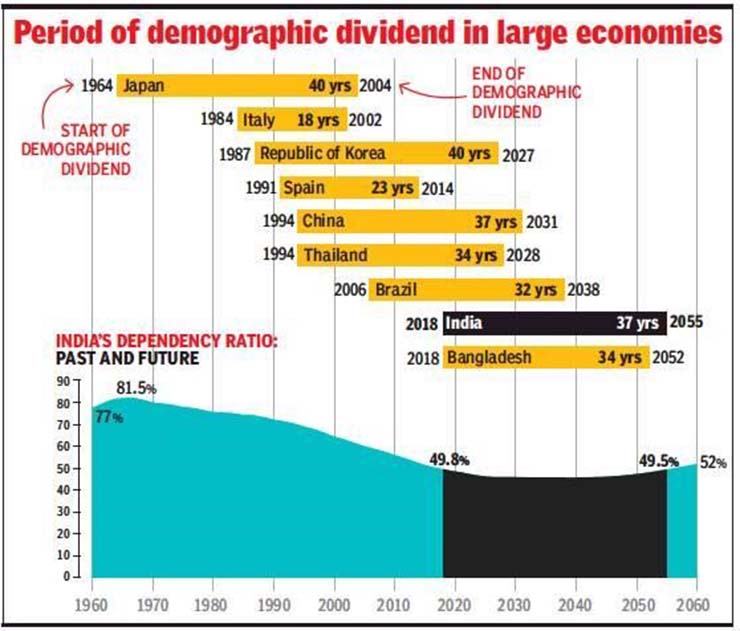

The United Nations Population Fund defines a demographic dividend as the potential for substantial national economic payoff in a period in which the working-age population is healthy, educated, and gainfully employed, with a low proportion of young dependents. India is said to have entered into a 37-year period of demographic dividend, lasting from 2018 to 2055, because of a declining dependency ratio (see Figure 1).

Over two-thirds of India’s population are of working age, with the elderly constituting less than 7 per cent. And while all may appear hunky-dory, the youth unemployment situation paints a grim picture.

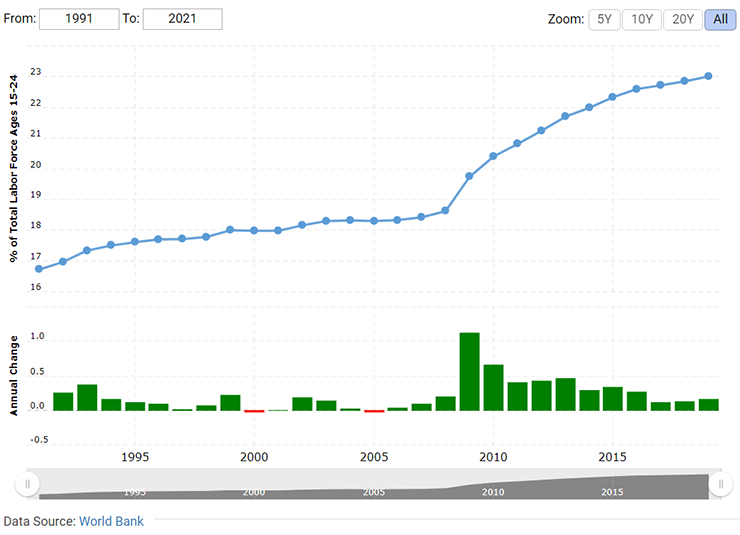

With the youth unemployment rate having increased every year since 2005, all the way from 18% to 23% in 2019 (see Figure 2), India’s population is young and frustrated. It is also worth noting that the youth unemployment rate has been far higher than the overall unemployment rate over the entire period of reference, with the latter spiking above 7% in the COVID-19 pandemic-affected 2020 compared to 5% in 2019, implying that the burden of joblessness is borne disproportionately by the country’s youth.

Governmental efforts towards generating gainful employment are hindered by the prevalence of illiteracy and malnutrition among youth.

Illiteracy creates a vicious circle

A major proportion of the unemployed is illiterate, rendering them poor and unable to earn enough to educate themselves, thereby creating a vicious circle. On the other hand, a 2019 report by UNICEF and NITI Aayog finds over half of Indian adolescents (about 6.3 lakh girls and 8.1 lakh boys) aged 10-19 years as being thin, short, overweight, or obese.

Job creation remains a big challenge

Then there exists the issue of upskilling the nation’s youth, to render them employable. The government’s Skill India programme marks a major step in this direction, with courses targeting employability in sectors including information and communications technology (ICT), electronics, BFSI, and agriculture. In a fillip to the ambitious campaign, which aims to provide job-relevant skills to more than 40 crore youth by the end of this year, a major Noida-based mobile handset manufacturing firm named Lava International has hired 260 ITI Berhampur students last month.

However, the government’s quest to significantly increase manufacturing jobs is likely to encounter immense challenges due to the extent of bureaucratic red tape that prevails in the country. A plethora of large MNCs discontinuing their India operations provides a case in point. German retailer Metro AG, Swiss construction-materials firm Holcim, US automaker Ford, UK’s Royal Bank of Scotland, US bikemaker Harley-Davidson and US banking giant Citibank have all curbed or downsized their operations in India in recent years, with regulatory unpredictability, dissuasive tariffs, red tape, and confounding land policies among the crucial reasons in many cases.

Dream of a manufacturing hub

It is, in fact, especially because of the intangible difficulties involved in establishing and running brick-and-mortar businesses in India, that the country has largely failed to ever establish itself as a global manufacturing hub since independence despite the abundance of low-cost labour. Even the New Economic Policy of 1990-91, with its focus on liberalisation, privatisation and globalisation, failed to stimulate the Indian economy’s secondary sector. It comes as no surprise then that manufacturing contributes only about a sixth of India’s GDP, despite India being the fastest-growing large economy.

Notably, much of India’s growth over the past few decades has been on the back of a massive expansion of its services sector, which is nowhere near as labour-intensive as its manufacturing counterpart. Consequently, the nation has since witnessed large periods of so-called jobless growth, often not captured in official unemployment statistics which only capture chronic unemployment.

Malnourishment among youth must end

While the Skill India initiative is praiseworthy in addressing the demand side of the labour market by gearing youth toward meaningful employment in various sectors by upskilling and training them appropriately, India must tackle the widespread malnourishment in Indian children and adolescents.

The mid-day meal scheme (MDMS), which was discontinued in schools and Anganwadis for over two years in most parts of the country due to the ongoing pandemic, has thankfully been or is close to being recommenced in most participating states. However, complete normalisation still appears some way off. Moreover, problems relating to procurement have often plagued the MDMS, with provisions for Anganwadis having been repeatedly hindered or thwarted by ill-planned attempts at central procurement and the related corruption.

Predictable regulatory environment needed

On the supply side, while land and labour reforms remain politically hot potatoes for any government, the salience of removing bureaucratic red tape in harnessing the benefits of India’s favourable demography cannot be overemphasized. It must also be appreciated that returns from regulatory shock therapy are subject to rapidly diminishing returns, and a predictable regulatory environment is necessary for attracting private investments.

-The author is serving as a Fellow at Observer Research Foundation. Views expressed are personal and do not necessarily reflect the views of Raksha Anirveda