AT THE time of its independence, India inherited the defence production capability created by the British over the years initially to sustain their hold over the sub-continent and later to sustain their war efforts in the 1940s.

Starting with a gun factory, set up at Ishapore in 1787 the production capability had expanded considerably by the time they left India in 1947, leaving behind a chain of ordnance factories and companies like Hindustan Aircraft Limited and the Garden Reach Workshop Limited, which later on morphed into public sector undertakings (PSUs).

Defence production has come a long way in since then but only after passing through a prolonged phase of inertia for almost quarter of a century. This phase was marked by dependence on the legacy systems, occasional purchases and manufacturing in India by a few public sector units and the departmentally run ordnance factories to a limited extent.

Even the wars with China and Pakistan in 1962 and 1965 respectively did not bring about any change in the policy of according primacy to development goals. Delivering the budget speech for 1963-64 within months of the disastrous war with China, the then finance minister told the parliament that it would not be prudent ‘to provide for the paramount claims of defence by sacrificing the claims of development’.

Even the wars with China and Pakistan in 1962 and 1965 respectively did not bring about any change in the policy of according primacy to development goals. Delivering the budget speech for 1963-64 within months of the disastrous war with China, the then finance minister told the parliament that it would not be prudent ‘to provide for the paramount claims of defence by sacrificing the claims of development’.

A similar statement was made in the budget speech of 1966-67, following the war with Pakistan. “It has always been our policy to restrict expenditure on defence to the maximum extent possible so as to conserve all possible sources for securing the well-being of our people”, the finance minister told the parliament.

Though he also said that the nation could not “afford to take any chances with the security of the nation, devoted though we are to the cause of peace”, there was practically no increase in defence capital outlay in the budget presented by him.

All this changed in a significant way with the signing of the Indo-Soviet Treaty on Peace, Friendship and Cooperation August 1971. To be sure, defence cooperation between the two countries had started much earlier, the 1971 treaty arguably took the cooperation to a different level with substantial transfer of technology to the Indian public sector undertakings and the ordnance factories.

All this changed in a significant way with the signing of the Indo-Soviet Treaty on Peace, Friendship and Cooperation August 1971. To be sure, defence cooperation between the two countries had started much earlier, the 1971 treaty arguably took the cooperation to a different level with substantial transfer of technology to the Indian public sector undertakings and the ordnance factories.

This phase, marked largely by licensed-production based on transfer of technology, lasted till the USSR disintegrated in 1991. By this time, however, the defence establishment had realised that India must move towards self-reliance in defence production. Accordingly, a roadmap was evolved by late Dr APJ Abdul Kalam to increase the share of procurement from the indigenous sources from 30 per cent to 70 per cent over the next 10-15 years.

The roadmap had little impact on India’s dependence on foreign technology and equipment till the government decided to take some concrete steps following the Kargil war in 1999. Within the next two years, defence production was opened to the private sector and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) permitted up to 26 per cent. Many other structural and procedural changes were made to streamline defence procurement. The first Defence Procurement Procedure (DPP) was promulgated in 2002.

The roadmap had little impact on India’s dependence on foreign technology and equipment till the government decided to take some concrete steps following the Kargil war in 1999. Within the next two years, defence production was opened to the private sector and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) permitted up to 26 per cent. Many other structural and procedural changes were made to streamline defence procurement. The first Defence Procurement Procedure (DPP) was promulgated in 2002.

Efforts at systematising defence manufacturing and acquisitions have continued since then. In 2006, the ‘Make’ procedure was introduced in the DPP to promote indigenous design, development and manufacture of the prototypes of high-technology complex systems. The same year a Defence Offset Policy was adopted to boost the fledgling Indian defence industry. In 2011, a Defence Production Policy was laid down. Since 2014, there has been a renewed effort to energise defence production under the government’s ‘Make in India’ initiative.

Although the private sector is now playing a much larger role in defence production than was the case till the turn of the century, the main indigenous source of supply of defence products continue to be the 41 ordnance factories and 9 Defence PSUs. The equipment, weapon systems, other platforms and ammunition supplied by them are largely made with the help of, or based on, technology-transfer from the foreign manufacturers.

Although the private sector is now playing a much larger role in defence production than was the case till the turn of the century, the main indigenous source of supply of defence products continue to be the 41 ordnance factories and 9 Defence PSUs. The equipment, weapon systems, other platforms and ammunition supplied by them are largely made with the help of, or based on, technology-transfer from the foreign manufacturers.

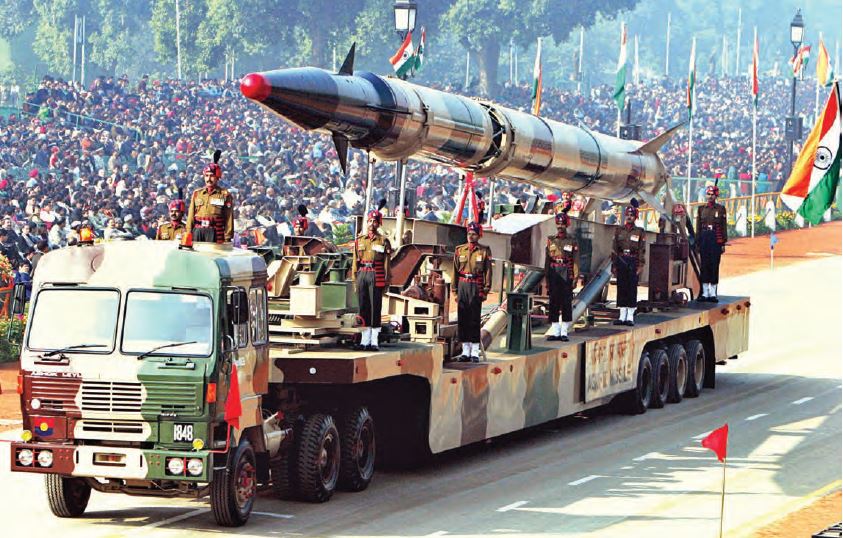

The products manufactured by the Defence PSUs and the ordnance factories include arms and ammunition, tanks, armoured vehicles, heavy vehicles, fighter aircraft and helicopters, warships, submarines, missiles, ammunition, electronic equipment, earth moving equipment, special alloys and special purpose steels. The total value of their production has gone up from Rs 43,746.48 crore in 2013-14 to Rs 52,968.13 in 2015-16.

However, there have been concerns about the productivity of these units. The cost and time overruns are endemic and, in some cases, the quality of the products has been questionable. Most of the Defence PSUs have not been making no, or considerably low, profits. Their combined profit increased by less than Rs 200 crore from Rs 4,470.77 crore in 2013-14 to Rs Rs 4,625.34 crore in 2015-16.

Self-reliance in defence production depends to a large extent on research, design and development. This has largely been the exclusive domain of the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO), which is a department of the Ministry of Defence (MoD). It has been engaged in research efforts aimed at making India self-sufficient in defence technologies relating to missiles, radars, sonars, electronic warfare, engineering systems, surveillance and reconnaissance systems, just to name a few.

Self-reliance in defence production depends to a large extent on research, design and development. This has largely been the exclusive domain of the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO), which is a department of the Ministry of Defence (MoD). It has been engaged in research efforts aimed at making India self-sufficient in defence technologies relating to missiles, radars, sonars, electronic warfare, engineering systems, surveillance and reconnaissance systems, just to name a few.

The DRDO has also been working to provide state-of-the-art communication systems, electro-optics, night vision devices, information security products, naval and airborne weapons etc. Each of these is being, or has been developed, using indigenous manufacturing and testing facilities to the maximum possible extent.

Meanwhile, the private sector has made some significant strides. Major players like Larsen & Toubro, Tata Group, Mahindra Defence Systems, Bharat Forge and 6,000-odd Micro-Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) are playing a greater role. According to MoD’s Annual Report for the year 2016-17, the Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion (DIPP) has issued 342 Industrial Licences to 205 private companies till June 2016 for manufacturing a wide range of defence items and 52 of these licensed companies have so far commenced production and started supplying equipment to the armed forces.

The Minister of State for Defence informed the Lok Sabha on 07 February 2018 that expenditure on procurement from the Indian companies, presumably including those in the public sector, had increased from Rs 39,598.91 crore in 2014-15 to Rs 41,872.03 crore in 2016-17, out of total procurement of Rs 65,583.77 crore and Rs Rs 69,150.12 crore respectively.

This is impressive but clearly not good enough for two reasons. One, this dissembles the fact that India is currently the largest importer of arms, accounting for 12 per cent of the global imports between 2013 and 2017. Two, no big ticket contracts have been awarded to the Indian companies in the recent years, though this is not for want of an effort by the government which has taken several steps in the past four years to change the narrative.

In 2016 a new procurement category, called ‘Buy (Indian Designed, Developed and Manufactured), was created. This, along with other categories, such as Buy (Indian) and Buy and Make (Indian), focuses on ensuring involvement of the private sector in defence manufacturing. About 60 per cent of the new procurement proposals have been approved in principle under these categories which means that only the Indian companies will be able to participate in the tender.

More importantly, between 01.04.2014 and 30.11.17, as many as 119 contracts involving Rs 1,16,523 crore have been signed with the Indian companies whereas only 68 contracts involving Rs.1,24,291 crore have been signed with foreign companies. These figures could go up significantly as contracts for ‘Make’ projects entailing development of the prototype of defence products start getting awarded and the projects being funded by the DRDO under the Defence Technology Fund start showing results.

More importantly, between 01.04.2014 and 30.11.17, as many as 119 contracts involving Rs 1,16,523 crore have been signed with the Indian companies whereas only 68 contracts involving Rs.1,24,291 crore have been signed with foreign companies. These figures could go up significantly as contracts for ‘Make’ projects entailing development of the prototype of defence products start getting awarded and the projects being funded by the DRDO under the Defence Technology Fund start showing results.

But clearly this is not enough as challenges in promoting indigenous defence production still abound. To begin with, there seems to be no overarching plan for achieving self-reliance through indigenisation. Consequently, several policy initiatives are being taken in a disjointed manner without tying up all lose ends.

A case in point is introduction of the Strategic Partnership model under which Indian companies will be required to make platforms like aircraft, helicopters, submarines and armoured fighting vehicles with the help of transfer of technology from the foreign manufacturers chosen by the MoD.

Not only does this model overlap with several other existing modes of procurement, such as Buy and Make, Buy and Make (Indian) and Make, but enough thought does not seem to have been given to the process of selecting the Indian companies as potential strategic partners. No wonder then that more than a year after the model was introduced the process of selecting the Indian companies is yet to begin.

Not only does this model overlap with several other existing modes of procurement, such as Buy and Make, Buy and Make (Indian) and Make, but enough thought does not seem to have been given to the process of selecting the Indian companies as potential strategic partners. No wonder then that more than a year after the model was introduced the process of selecting the Indian companies is yet to begin.

This is also true of the steps taken by the government to raise the cap on FDI in defence to 49 per cent which has resulted in inflow of just about Rs one crore by way of investment in the last four years. It is a no brainer that investment will come only if there is a business case. With a virtual 49 per cent cap on FDI the foreign investors are unlikely to invest in joint ventures as it does not give them a decisive say in its management. It is not surprising that the government is already thinking of raising it further to 74 per cent but such vacillation reflects poorly on policy making.

Be that as it may, the pace and quality of decision-making within the government in general and MoD in particular have put paid to many a promising project, such as manufacture of transport aircraft to replace the Avro-fleet of the Indian Air Force. The project, which by now would have been on way to creating a parallel aircraft manufacturing capacity in the private sector, has been hanging fire for the more than five years.

Many of these problems are because of the procedural complexities and a total disconnect between aspiration of achieving self-reliance and the financial viability of achieving those goals. The problem also lies with a fractured organisational structure with different entities within the MoD handling research, production and procurement. The procurement process itself is handled by several agencies with no single-point accountability.

A committee set up by the MoD in 2016 had recommended setting up of a semi-autonomous Defence Acquisition Organisation to ensure a holistic approach to promote indigenous research and development, production of equipment and timely procurement of the capabilities required by the armed forces with due regard to the financial constraints. It is time to give it a serious thought.

– The author is Ex-Financial Advisor (Acquisition), Ministry of Defence

–The writer is a former Financial Advisor (Acquisition), Ministry of Defence. The views expressed are personal and do not necessarily reflect the views of Raksha Anirveda