The Indian Navy is currently down to a single aircraft carrier, the INS Vikramaditya. This means if the vessel suffers a boiler burst or has to undergo normal maintenance, the Navy may have to fight a war without its flagship. In view of this critical situation, Navy chief Admiral Karambir Singh says India requires at least three aircraft carriers to meet its operational needs in the region.

The good news is that work on INS Vikrant (codenamed Indigenous Aircraft Carrier-1 or IAC-1) is currently moving along at a brisk pace, with the 40,000 tonne ship’s gas turbines expected to start firing by the third quarter of this year, and basin trials likely in February-March 2020. Basin trial is the testing of ship machineries and equipment in floating conditions before the sea trials. Aviation trials, which are expected to commence by February 2021, will take about two years and the carrier is expected to be commissioned into the Navy in early 2023.

Vice Admiral AK Saxena, Controller of Warship Production and Acquisition, said at a FICCI seminar earlier this year: “IAC-1 is presently moving at a very, very brisk pace and the plans are to go in for basin trials sometime in February-March next year. That will be followed with a series of contract of sea trials and ultimately culminate in to delivery of the ship sometime in early 2021. Towards this, hectic activity is going on, on board the ship.”

In parallel with the IAC-1 project, the infrastructure required to service these super-massive ships is gradually coming online. On September 28 this year, Defence Minister Rajnath Singh inaugurated the Navy’s largest dry dock to date at the Naval Dockyard in Mumbai. Named ‘Aircraft Carrier Dry Dock’, the 281 metre long, 45 metre wide, and 17 metre deep facility is capable of accommodating ships of up to 90,000 tonnes.

On November 3, 2019, Cochin Shipyard Limited (CSL) signed a Rs 3,000 crore phase-III construction contract which covers the operational and harbour acceptance trials of various equipments and systems installed onboard and also the sea trials of the carrier as well as the post-delivery activities of the vessel including support on weapon and aviation trials. The project cost is currently Rs 19,341 crore.

How many carriers are enough?

The Navy is certain that the way of the future is to operate Carrier Battle Groups (CBGs) that can project power. The logic is that a third carrier is needed to ensure that at least two are at sea at any given point. The INS Vikramaditya is based at Karwar while the INS Vikrant will be based at Visakhapatnam. The third carrier would be rotated around whenever one of these is in refit or in need for repairs.

According to the current Navy Chief, “We are pursuing induction of the third carrier to ensure we have the requisite force levels to meet all operational imperatives.” Admiral Karambir Singh also pointed to a power competition for the maritime domain, referring to the increase in Chinese force levels to match the US that uses carriers as its main weapon to project power worldwide. “The ongoing crisis in the Strait of Hormuz, confrontations in the South China Sea and increasing use of naval platforms for political signalling are unmistakable fallouts of the great power competition in the maritime domain,” he said.

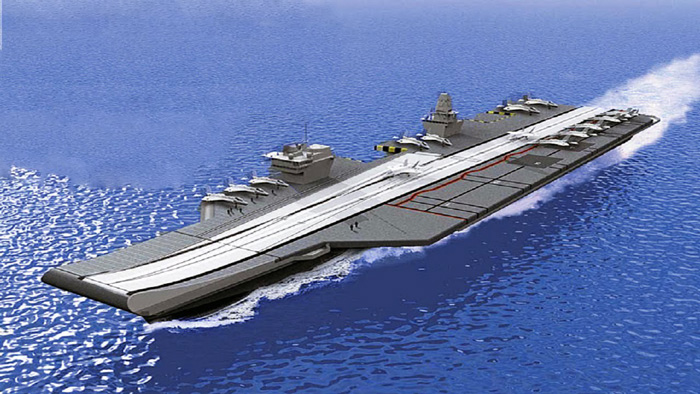

But the Defence Ministry is yet to give the initial approval for construction of the 65,000-tonne IAC-II, which was first sought in May 2015. The Navy has scaled down its plan for IAC-II to have nuclear-propulsion to bring down the overall cost to about Rs 45,000 crore.

China already has six to seven warships deployed in the Indian Ocean Region at any given time. The permanent presence of a Chinese CBG in the region within the next few years, and possibly two by 2028, will create a power imbalance in India’s neighbourhood. If the government green lights the project, the earliest IAC-II can enter service is 2031. By then, China will have four CBGs.

If okayed, Vishal will not follow the same model as Vikrant. Its launch system is to be CATOBAR (catapult assisted takeoff but arrested recovery) or, more precisely, its new generation: EMALS (electromagnetic aircraft launch system). Such a system is being developed by the Americans, and an Indo-American working group has been formed to explore the possibility of technology transfer. If Vishal is equipped with EMALS, it will make the carrier capable of working with heavier planes thereby allowing the Indian Navy to launch carrier-based AWACS aircraft such as the American E-2 Hawkeye. Currently, the sole Indian CBG uses low-endurance and limited-range Kamov helicopters for intelligence gathering.

Maritime strategy

There’s no denying that aircraft carriers are expensive assets, but only when one considers their initial cost of acquisition. According to a report by the New Delhi-based Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA), “When this cost is divided over the average life of an aircraft carrier, which could be anywhere from 40 to 45 years, it works out similar to two destroyers with an average life span of 25 years. This includes the fact that an aircraft carrier over its lifespan might service squadrons from two different technological generations. Added to this, when an aircraft carrier is constructed indigenously, like India’s Vikrant and Vishal, it creates enormous job opportunities, encourages indigenous shipbuilding and provides business to local industries.”

The Indian Maritime Doctrine defines sea control as “a condition where one is able to use a defined sea area, for a defined period of time, for one’s own purposes and at the same time deny its use to the adversary”. Considering a prolonged conflict, this would translate to enforcing credible power projection and maritime trade blockade (against Pakistan) and trade intervention (against China). In today’s context, the only naval platform that can enforce this is the aircraft carrier. The carrier air wing can keep under surveillance areas up to hundreds of kilometres around it, while attacking hostile warships directly or guiding other friendly assets to do so. Land based air assets and other naval warships have severe limitations in achieving the same results.

The new Maritime Doctrine lays out that the Indian Navy’s strategic vision will no longer be limited to the northern Indian Ocean, but will extend to distant trouble spots. Indian Navy flotillas are now a familiar sight in the South China Sea where they conducts patrols to dent China’s claim that it is a Chinese lake. Such a doctrine cannot be implemented without an adequate number of CBGs. Plus, in the event of a military conflict, a carrier is the only naval asset that can provide total protection to all floating assets – other naval vessels, offshore oil platforms and merchant shipping carrying strategic commodities to India.

Vikrant at war

The Indian Navy’s early investment in the carrier paid handsome dividends. In the 1971 War, the INS Vikrant, supported by just two warships, bottled up the Pakistan Navy’s eastern wing in Chittagong harbour. More than 93,000 Pakistan Army troops were planning to escape on board these ships which were to make a dash for the open sea. The Vikrant’s vigil – and the sinking of several Pakistani merchant vessels by its jets – hastened the largest capitulation of troops since General Paulus’ Sixth Army surrendered in Stalingrad in 1943.

The Indian Navy received another bonus thanks to its flagship. In November 1971, well over a month before the declaration of war, the Pakistan Navy despatched an American gifted submarine named PNS Ghazi – with the mission to sink the Indian carrier.

When Indian intelligence got wind of the Ghazi’s plan, the Navy hid the carrier in the Andaman & Nicobar Islands – over 1,500 km from the mainland. The navy then built an elaborate ruse that lured the Ghazi towards India’s southern coast. First, it positioned its largest warship, INS Rajput, off Visakhapatnam harbour and created heavy radio traffic that mimicked the Vikrant’s. Secondly, the port authorities placed huge orders for food and supplies that would normally be required when a ship of Vikrant’s capacity sails in.

The Ghazi took the bait and started laying mines in the port’s channel. But the hunter became the hunted on December 4 when it blew up and sank in the harbour. While the Indian Navy claimed that it was the INS Rajput’s depth charges that caused the explosion, the Pakistanis say their submarine was destroyed by an internal explosion. Whatever caused the explosion, the catalyst of the sinking of the Pakistani submarine was the Vikrant.

Way forward: Look to the past

Since Rig Vedic time approximately 5,000 years ago up to the last Chola kings (800 years back), the Indian Ocean was literally India’s ocean. However, in the second half of the previous millennium, India was ruled by land-centric rulers from Central Asia who had little maritime knowledge or interest. Consequently, India yielded control of the sea to the European powers.

However, with the rise of the Marathas in the early 18th century, the focus on sea power returned. The Marathas enjoyed many tactical successes against the Western navies. Notable among these was the Maratha blockade of British-held Mumbai port that led to the British East India Company ceding a ransom of 8,750 pounds. In the year 1721 the Maratha Navy even defeated a joint Portuguese-British assault.

The Maratha Admiral of the Fleet Kanhoji Angre defeated every Western navy of his day. For 33 years until his death in 1729, the Indian fleets remained undefeated. Wrote British historian Charles Kincaid in the History of the Maratha People: “Victorious alike over the English, Dutch and the Portuguese, the Maratha Admirals sailed the Arabian Sea in triumph.”

Although the old dream of making the Indian Ocean into India’s ocean is no longer a component of the Navy’s doctrine, dominating the blue waters is part of the plan. Or to use former Admiral Vishnu Bhagwat’s words, enhancing India’s force projection capability is a “national requirement on the strategic frontier, not at the doorstep”.

– The author is a New Zealand based defence analyst. His work has been quoted extensively by leading think tanks, Universities and publications world wide