Developing an indigenous aeroengine remains one of India’s most challenging yet critical technological ambitions. For decades, India has sought to master the complex technology of jet engines for military aircraft, a capability that underpins true defence autonomy. The journey has been marked by optimism, setbacks and valuable lessons, but recent developments signal a renewed and more confident push towards self-reliance in this vital domain.

Strategic Importance of Indigenous Aero Engines

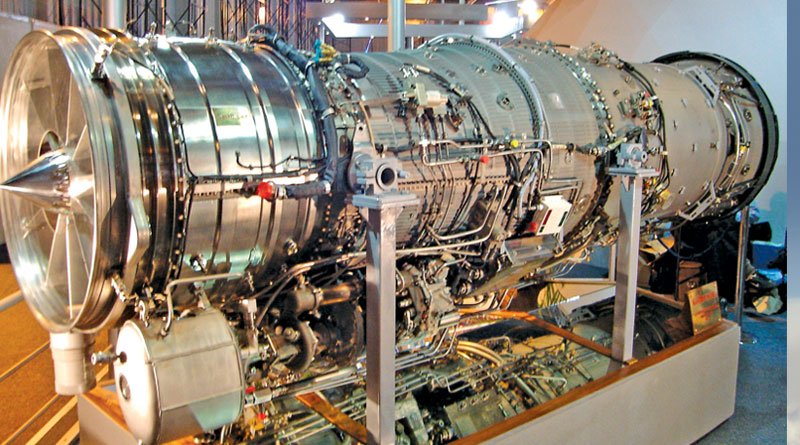

Jet engines are the heart of modern combat aircraft, and their complexity makes them among the most difficult defence technologies to master. India’s reliance on foreign suppliers for engines — such as the General Electric F404 powering the Tejas Mk-1 and the Russian AL-31FP for the Su-30 MKI — exposes it to strategic vulnerabilities including supply chain disruptions, export restrictions and maintenance dependencies. As geopolitical tensions escalate and global technology transfers become more guarded, India’s imperative to develop homegrown aero engines has never been more urgent.

Limits of Foreign Technology Transfers

For years, India pursued technology transfer (ToT) agreements with foreign original equipment manufacturers (OEMs), hoping to leapfrog into advanced aero engine manufacturing. However, critical technologies — such as advanced materials science, single-crystal turbine blades, thermal coatings and combustion systems — remain closely guarded secrets, rarely included in ToT packages. This realisation has shifted India’s focus decisively towards indigenous development, acknowledging that true mastery can only come from within.

Kaveri Engine: Lessons from a Pioneering Effort

India’s indigenous aero engine journey has been spearheaded by the Gas Turbine Research Establishment (GTRE) under the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO). The flagship Kaveri engine programme, initiated in the 1980s to power the Tejas Light Combat Aircraft (LCA), faced significant technical challenges. Despite over two decades of development and investment exceeding ₹2,000 crore ($240 million), the Kaveri engine fell short of its thrust (target ~90 kN) and weight goals, leading to its decoupling from the Tejas programme in 2014.

Nevertheless, the Kaveri programme was far from a failure. It laid a critical foundation by building indigenous expertise in metallurgy, compressor design, thermodynamics and testing infrastructure. The engine’s dry version, producing about 49-51 kN thrust, has now been cleared for inflight testing on unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) like the Ghatak stealth UCAV, marking a significant milestone in India’s aero engine capabilities. This progress is being furthered by the ongoing Kaveri 2.0 programme, which aims to develop advanced derivatives (K9 and K10 engines) capable of 90-100 kN thrust with afterburners, comparable to global benchmarks like the GE F4144 turbofan engine.

Infrastructure and Testing: Building the Backbone

A key enabler of India’s aero engine ambitions is the development of state-of-the-art testing infrastructure. The GTRE’s 130 kN Twin Engine Test Bed Facility near completion in Bengaluru will allow rigorous endurance and performance testing of high-thrust engines, including the Kaveri and future engines for the Advanced Medium Combat Aircraft (AMCA). Operational by late 2025, this facility is a cornerstone for validating indigenous engine designs and accelerating development cycles.

Strategic Approaches: Competition, Consortium and Collaboration

To accelerate progress and mitigate risks, India is exploring multiple strategic models:

Parallel Competitive Programmes: Inspired by the US model where multiple OEMs compete (for instance, GE and Pratt & Whitney), India could fund competing teams to foster innovation and accountability, reducing dependency on a single entity.

Consortium Model (Public-Private Partnership): Similar to Airbus or Eurojet, this model pools resources and expertise from government labs, private industry, and academia, sharing risks and benefits.

Hybrid Approach: GTRE leads fundamental R&D while private firms handle engineering development, manufacturing, and refinement, combining institutional knowledge with market agility.

These approaches aim to harness the strengths of both public and private sectors, ensuring sustained innovation and production capability.

Private Sector Engagement: A New Paradigm

The entry of the private sector into India’s defence industry has transformed the landscape in several key segments such as cruise missiles, towed artillery guns, air-dropped artillery, infantry combat vehicles, rifles and ammunition. Private sector collaboration could emerge as a critical catalyst in accelerating India’s aero engine development, addressing the complex technological, financial and organisational challenges that have historically slowed progress.

Jet engines are the heart of combat aircraft, and their complexity makes them among the most difficult defence technologies to master. India’s reliance on foreign suppliers for engines exposes it to strategic vulnerabilities. Hence, India’s imperative to develop homegrown aero engines has never been more urgent

1. Pooling Expertise and Resources Through Industry Consortia

Leading private players such as Bharat Forge, Tata Advanced Systems, Godrej Aerospace, Mahindra Defence, and Larsen & Toubro (L&T) are actively advocating for and forming consortia to jointly develop high-thrust jet engines, including a 110 kN class engine for the Advanced Medium Combat Aircraft (AMCA). Such consortia enable:

Shared investment burden: Aero-engine development requires billions of rupees and decades of R&D. Collaborative funding reduces risks and spreads costs across multiple stakeholders.

Complementary capabilities: No single company in India currently possesses the full spectrum of expertise needed. Consortia brings together metallurgy, precision forging, aerodynamics, digital control systems, and manufacturing excellence under one umbrella.

Innovation through competition and cooperation: Collaboration fosters cross-pollination of ideas, while internal competition within consortia drives higher standards and faster problem-solving.

Baba Kalyani of Bharat Forge has emphasised that industry consortia are essential to developing ‘Made in India’ aero engines, mirroring successful global models like the European Clean Sky initiative where industry and academia collaborate on propulsion technologies.

2. Leveraging Private Sector Manufacturing Strengths

Private companies bring advanced manufacturing capabilities, supply chain management, and agility that can complement government research institutions like GTRE and Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL). For example:

Bharat Forge’s expertise in high-precision forging and superalloy processing is critical for manufacturing turbine blades and discs.

Tata Advanced Systems, Godrej Aerospace, and Mahindra Aerospace already produce complex aero-engine components for global OEMs like GE Aerospace, demonstrating their ability to meet stringent quality standards and export globally.

The private sector’s entry into India’s defence industry has transformed the landscape. Private sector collaboration can emerge as a critical catalyst in accelerating India’s aero engine development, addressing the complex technological, financial, and organisational challenges that have historically slowed progress

L&T has proposed a fully indigenous 110 kN engine development programme, leveraging lessons from the Kaveri engine, and is urging the government to prioritise technical merit over lowest-cost bidding to ensure quality and innovation. This manufacturing prowess can shorten development cycles and improve production readiness.

3. Enhancing R&D Through Academia and Startups

Private sector collaboration extends beyond large firms to include startups and academic institutions such as IITs and the Indian Institute of Science. These entities contribute cutting-edge research in materials science, additive manufacturing, AI-driven design optimisation, and propulsion technologies. Close partnerships between industry, academia and government labs foster talent development and retention of skilled engineers and scientists, accelerated innovation cycles, and access to emerging technologies that can be rapidly prototyped and integrated.

Such a multi-stakeholder ecosystem addresses the knowledge gaps that have hindered previous indigenous engine efforts.

4. Reducing Dependence on Foreign Technology and Accelerating Learning

Private sector-led consortia can better negotiate technology transfer agreements with foreign partners, ensuring that critical core technologies — especially the hot core section of the engine — are indigenised rather than merely assembled under licence. Baba Kalyani highlighted that collaborative private sector efforts on a 110 kN engine would serve as a ‘learning platform’ enabling Indian firms to design and produce engines entirely on their own eventually.

5. Creating a Competitive and Accountable Development Environment

By involving multiple private companies, India can adopt a model akin to the US system where competing teams develop engine prototypes, driving innovation and accountability. This contrasts with previous monopolistic public sector approaches and can prevent bottlenecks and complacency.

Foreign Partnerships: Cautious Engagement

While the private sector’s expertise in precision engineering and materials science — gained through participation in commercial aeroengine supply chains — is a strong foundation, the leap to military-grade engines involves overcoming significant technological and temporal challenges. Experts suggest that without foreign collaboration, developing a fully indigenous high-thrust military engine might take 12-15 years, longer than the 7-9-year timeline desired by the AMCA programme.

Rolls-Royce has offered India a co-development deal, marking its potential first major military engine collaboration. However, Rolls-Royce’s expertise is primarily in commercial aero engines, raising questions about their ability to deliver high-thrust after-burning military engines and the extent of technology transfer India would receive. Any foreign partnership must prioritise deep technology sharing over mere assembly roles to truly benefit India’s strategic autonomy.

India’s indigenous aero engine quest must now be elevated to a national techno-strategic mission, akin to landmark programmes like ISRO’s Chandrayaan, the DRDO’s Integrated Guided Missile Development Programme or the nuclear weapons programme. Its success will enable India to achieve true defence autonomy

National Mission for Self-Reliance

India’s indigenous aero engine quest must now be elevated to a national techno-strategic mission, akin to landmark programmes like ISRO’s Chandrayaan, the DRDO’s Integrated Guided Missile Development Programme or the nuclear weapons programme. In the face of evolving security challenges and geopolitical uncertainties, developing indigenous aero engines is not merely an engineering challenge but a strategic necessity. Success will enable India to achieve true defence autonomy, reduce operational vulnerabilities, and position itself as a global aerospace hub.

India’s journey to mastering the jet engine will be long and complex but indispensable. With renewed government focus, private sector dynamism, infrastructural investments, and lessons from past efforts, the country can transform its aero engine ambitions into operational reality, powering the skies with engines built in India, for India.

–The writer is a globally cited defence analyst based in New Zealand. The views expressed are of the writer and do not necessarily reflect the views of Raksha Anirveda