On May 7, 2025, the Indian military required merely 23 minutes to breach Pakistan’s Chinese-supplied air defence network. The Indian Air Force (IAF) successfully evaded, jammed, and in some cases destroyed the imported air defence units, enabling the successful targeting of terrorist infrastructure on Pakistani soil.

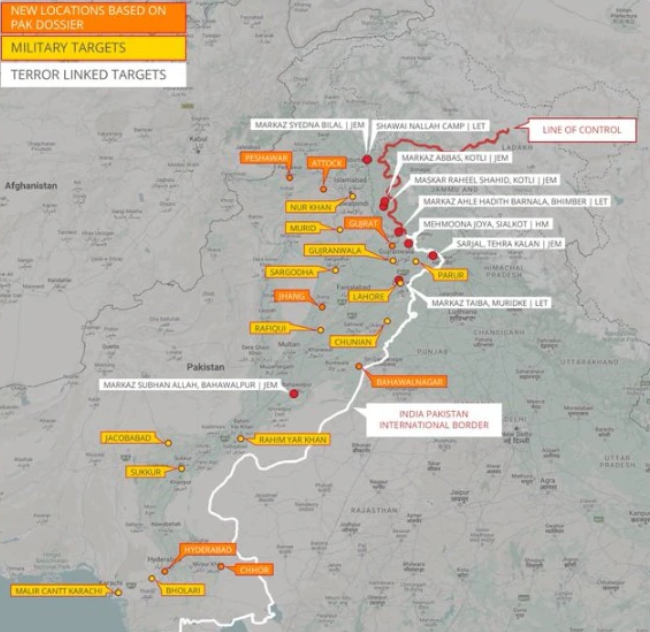

Over the following days of Operation Sindoor, Indian strikes were conducted against multiple Pakistani air bases, as well as radar and missile sites, including those at Noor Khan Air Base in Chaklala and Rahimyar Khan, with surgical precision (see Figure 1). These operations involved the application of loitering munitions to seek and neutralise high-value military targets, despite Pakistan’s deployment of Chinese air defence systems like the HQ-9 and HQ-16/LY-80. Meanwhile, the abject failure of the Chinese anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) architecture may have come as a surprise in certain quarters, but these failures are, in fact, part of a long-standing tradition of abysmal performances by Chinese air defence exports to Pakistan, with the HQ series of air defence systems at its core.

The HQ series originated in the late 1950s with the development of the HQ-1 by the Changfeng Electromechanical Technology Research and Design Institute. Over the following decades, China developed various models, including the HQ-12, HQ-9, and HQ-22, each with its unique characteristics and capabilities.

China began exporting air defence systems to Pakistan in the mid-1960s, with arms transfers accelerating over the following decades. The HQ-16/LY-80 and the more modern HQ-9 formed the mainstay of these exports, becoming a critical part of Pakistan’s military posture against India.

Over the following days of Operation Sindoor, Indian strikes were conducted against multiple Pakistani air bases, as well as radar and missile sites, including those at Noor Khan Air Base in Chaklala and Rahimyar Khan, with surgical precision. The abject failure of the Chinese anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) architecture are, in fact, part of a long-standing tradition of abysmal performances by Chinese air defence exports to Pakistan, with the HQ series of air defence systems at its core

Manufactured by China Aerospace Science and Technology Corp (CASC), the HQ-16 was touted to be capable of engaging aerial threats, except for very low-flying targets, at distances of up to 40 km and at altitudes ranging from 400 to 10,000 metres, with its effective engagement range against cruise missiles limited to 3.5–18 km. Notably, many Chinese military websites had described the HQ-16 as an effective deterrent against the Indo-Russian BRAHMOS missile.

On the other hand, the HQ-9 family is based on the Russian S-300 air defence system and has also been compared to the US-made Patriot system (see Figure 2). While the HQ-9B has a shorter range than some S-300 variants, it was considered to have superior electronic countermeasures and enhanced capabilities against stealthy targets at shorter ranges. With a price tag significantly lower than Western alternatives like the Patriot PAC-3, it appeared to offer an attractive choice for countries seeking advanced air defence systems without Western restrictions.

Inducted by the Pakistan Army in March 2017 to protect its airspace from incoming missiles and fighter jets, the HQ-16 is also deployed on the Pakistan Navy’s frontline Tughril-class (Chinese Type 054A/P) stealth frigates, housed within 32 vertical launch system (VLS) cells. Later, in October 2021, Pakistan’s armed forces commissioned the HQ-9/P (Chinese FD-2000) long-range air defence system, designed to engage aircraft and cruise missiles at ranges exceeding 100 km. However, these Chinese-origin systems have consistently underperformed in securing Pakistan’s airspace. Three notable failures predating India’s Operation Sindoor (May 2025) are outlined below:

Operation Bandar (February 2019):

On February 26, 2019, the Indian Air Force (IAF) conducted a precision airstrike on a Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM) terrorist camp in Balakot, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, in retaliation for the Pulwama attack that killed 40 Indian security personnel. Despite Pakistan’s HQ-16 systems being operational since 2017, IAF Mirage 2000s penetrated 80 km into Pakistani territory undetected, striking the target without interception. The failure of Pakistani radars and air defences—despite heightened alert levels—exposed critical gaps in its anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) network.

Such setbacks reflect poorly on China’s military-technical capabilities and may incentivise GHQ Rawalpindi to seek alternative suppliers… although this would be difficult given Islamabad’s high financial indebtedness to China

BRAHMOS Missile Incident (March 2022):

In March 2022, an accidentally launched Indian BRAHMOS missile entered Pakistani airspace, traveling 124 km in 3 minutes and 44 seconds before crashing near Mian Channu, Punjab – about 160 km away from the town of Bahawalpur in Pakistan’s Punjab province, which was among the urban centres at the receiving end of IAF’s precision strikes on May 7, 2025 during India’s Operation Sindoor (see Figure 3). The launch had originated from Sirsa in the Indian State of Haryana and entered Pakistan from Suratgarh in the Indian State of Rajasthan. Although Pakistan claimed to have tracked the missile, its HQ-9/P systems failed to intercept the supersonic projectile, raising doubts about their operational efficacy against high-speed threats. The missile’s supersonic velocity and low-altitude trajectory further highlighted systemic vulnerabilities.

The next trial by fire of Pakistan’s Chinese air defence assets occurred in January 2024, when Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps launched a series of drone and missile strikes against what it claimed were training camps of Sunni militant outfit Jaish-ul-Adl on Pakistani territory (see Figure 4). The projectiles evaded detection by Pakistani radars, which were afflicted by technical glitches, once again exposing lacunae in Pakistan’s so-called Comprehensive Layered Integrated Air Defence (CLIAD) architecture.

Such setbacks not only reflect poorly on China’s military-technical capabilities but may also incentivise Pakistan’s General Headquarters (GHQ) Rawalpindi to seek alternative suppliers for its A2/AD requirements. However, this option would be difficult given Islamabad’s crippling financial indebtedness to China and the extreme asymmetry in the China-Pakistan bilateral relationship. A more sustainable solution would require a concerted effort to develop indigenous capabilities—far exceeding piecemeal political statements of intent. Yet such efforts are likely to prove prohibitively costly without sustained foreign military assistance, encompassing both financial support and technological transfer, ideally sourced from partners other than Beijing.

The writer is an independent researcher with publications spanning diverse fields, including terrorism and counter-terrorism, foreign policy, climate finance, microfinance, maritime security, corporate finance, and industrial organisation.