A complex new era of military and security threats is challenging every government around the world to evolve the way it operates. The good news for India is that it can join the vanguard.

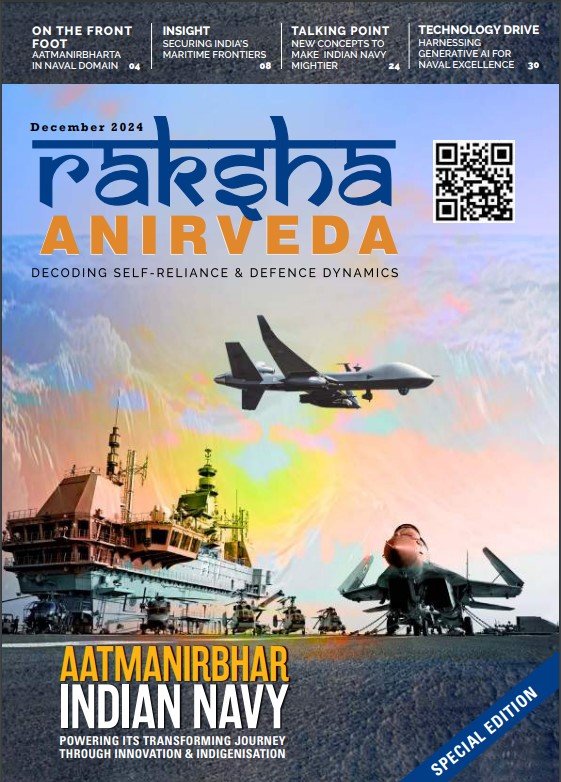

High altitude, long endurance remotely piloted aircraft, such as the MQ-9B SkyGuardian, are the bridges that can connect existing naval, air and ground forces from their current posture to new types of multi-domain operations.

The American aerospace and defense vendor General Atomics Aeronautical Systems, Inc. has led the way with the MQ-9 Reaper and other pace-setting aircraft, which change the game both because of what they can do on their own but also what they make possible as part of a larger force.

The company offers its clients many other vital products and services from its other divisions. The Electromagnetic Systems business builds the U.S. Navy’s successful Electromagnetic Aircraft Launching System for its new class of aircraft carriers. EMS is ready to build its unique carrier aircraft handling equipment for the French Navy and other operators of big aviation-centric warships.

The EMS business also builds advanced weapons including a high-energy laser that offers intense but precise destructive power from a remotely piloted aircraft and a multi-mission electromagnetic railgun, which adapts to a number of combat roles via projectiles flying at several times the speed of sound – fired without the use of chemical propellants.

Much of the support equipment necessary to wield these advanced applications, including power transmission systems, ordnance and so on, has been developed via internal research and development within the company. This enables GA to offer governments some of the most sophisticated aerospace and defense products in the world with less risk and less cost to their taxpayers given how much of the research and work already has been accomplished and proven.

To understand what the future could bring, however, it is necessary to start from the beginning.

GA’s core business is ASI’s remotely piloted aircraft. Models such as the SkyGuardian give commanders something they can’t get any other way: nonstop visibility over areas of interest, without the risk or cost associated with a human aircrew. With the ability to fly for 30 hours or more, groups of aircraft working in teams can keep an area under surveillance indefinitely, yielding a huge trove of insight about who comes, who stays, who goes and what takes place.

Remotely piloted aircraft revolutionized conflicts in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria and elsewhere because they could establish patterns of life, see where vehicles traveled, how subjects of interest conducted themselves on the ground, and much more.

The human pilots and sensor operators in control of these aircraft operate safely from ground stations, sometimes thousands of miles away. That means they can work in regular shifts from the comfort of a land base – as compared to air crews aboard an aircraft that must spend some of its mission flying back and forth from its operating area. One operator pilots the SkyGuardian while others operate the aircraft’s mission equipment.

This includes its electro-optical infrared sensor turret, which can transmit live, full-motion video during the day or night to commanders, intelligence officers or any others who need it. The SkyGuardian also has a Lynx multi-mode radar, which lets the aircraft make detailed maps, examine terrain for details as fine as wheel marks and see – electronically – through smoke, dust or clouds.

These aircraft, always under the control of their human crews, also can release weapons with precise and lethal effect, earning them reputations both among friendly and hostile forces on the ground. American commanders credited the mere presence of MQ-9A Reapers overhead in Iraq in 2019 with dissuading possible attacks by outside antagonists.

This, then, is the foundation on which multi-domain operations are built: A long-loitering, highly sophisticated patrol aircraft with millions of proven hours in combat. The next steps involve taking this proven baseline and expanding it in new ways to suit any number of combat requirements.

An airplane that can stay over a critical area for long periods of time is an ideal relay for communications networks, for example. It can provide data connectivity to forces on the ground, other aircraft, naval vessels or other units.

These networks, and these types of vital connectivity, are a plank of multi-domain operations. They mean that soldiers, airmen, sailors and others not only can stay in constant touch with each other, but see what the others see at the same time they do and, if necessary, act on it together.

For example, suppose an MQ-9B SeaGuardian — a SkyGuardian optimized with maritime sensors — patrolled over an important waterway and detected a suspicious fishing vessel, but it wasn’t able to fully discern its intentions. A surface warship such as the destroyer INS Chennai could use the locating data from the aircraft to fully investigate the ship, even if the larger warship hadn’t necessarily detected the other vessel with its own sensors.

This kind of cooperative engagement also works against submarines. MQ-9B is the first remotely piloted aircraft in its class that can search for and track these dangerous undersea threats.

This buys naval commanders significant flexibility. They might send one SeaGuardian, or several, out to conduct searches by themselves. Or they might prefer to operate them in an area along with surface warships such as the Chennai, which could send its Sea King helicopter to take part.

The SeaGuardian also is an excellent complement to India’s human-crewed P-8I Albatross maritime patrol aircraft. One reason is that it requires only a fraction of the cost to operate. If a larger, multi-engine, human-crewed maritime patrol aircraft costs about $35,000 per hour to fly, the MQ-9B costs about $5,000. A big, multi-engine patrol aircraft burns about 5,000 pounds of fuel per hour, as compared with roughly 200 per hour for the SeaGuardian.

This means the Indian navy could generate high-quality maritime domain awareness for a fraction of the cost of its larger patrol aircraft – saving them for the highest-demand applications or most urgent assignments. And when the P-8I does operate, it can do more, or cover more territory, with the assistance of one or a few MQ-9Bs operating in concert with it.

This teaming between the human-crewed and remotely operated aircraft permits many new concepts of operation: Indian navy commanders might decide to deploy everything at once and commit to a broad search above and below the surface.

Or they might decide to have SeaGuardian search until it developed a lead or spotted a target of interest – then have the P-8I join it to take part in the surveillance. In a crisis, or during a conflict, India’s government might adopt a doctrine in which it assigns its P-8I the responsibility to release weapons for the sake of having them come from a traditional aircraft with a local commander personally involved. Add this flexibility across the various domains of India’s military operations and the wide versatility quickly becomes obvious. The SeaGuardian or other patrol aircraft could screen Indian Navy, Army or Air Force units against threats both on land and at sea. They could make it possible for these forces, acting upon information from a remotely piloted aircraft far out to sea, to take action against an adversary or prepare for an incursion.

A number of modern militaries beyond India are just beginning to evolve this way into multi-domain operations – which presents yet more opportunities for New Delhi.

Selecting the MQ-9B SeaGuardian would mean India’s military operates the same advanced remotely piloted patrol aircraft as some of its most sophisticated allies.

The United States is the world’s largest operator of the MQ-9 family of remotely piloted aircraft; one demonstrated how well it could integrate with U.S. naval vessels in an exercise this spring. Japan’s coast guard and maritime self-defense forces have expressed interest in these aircraft and Japan hosted a landmark demonstration about the MQ-9B’s long-range patrol capabilities in 2020. The Royal Australian Air Force, meanwhile, is buying a fleet of sibling-model MQ-9B SkyGuardians.

The opportunities that these unified operators could create are legion. Not only would it be seamless for these key allies to share intelligence and reporting from each other’s aircraft, but the scale of the combined fleet would make any number of other integrated operations newly possible. The allies could cover more territory, across more parts of the Indian and Western Pacific oceans, with more innovative or disruptive capabilities from electronic and signals surveillance to anti-submarine search.

The advantages go beyond what the Indian, Australian, Japanese and American militaries could accomplish together operationally – although that is significant. The greater the size of the MQ-9B fleet operating around the region, the more economical it could become for all users.

Manufacturer GA-ASI offers a suite of sustainment services called SkyGuardian Support Solutions (SGSS), which guarantees aircraft uptime, the availability of spares and other essential services, all for an affordable cost per flight hour. It’s a model of aviation fleet sustainment long proven in the world of commercial aerospace that few other defense-sector manufacturers have offered in this way for remotely operated systems.

The MQ-9B is in demand around the world; the British Royal Air Force and the Belgian air force are among those bringing it into their fleets over the coming years. If India were to join them there’s no end to the new capabilities that it could realize – on its own and with its allies.