In our unending pursuit of knowledge, humanity is drawn to the mysteries beneath the ocean’s surface—an exploration frontier akin to both the cosmos and our planet’s origins. As we delve into this aquatic enigma, Unmanned Underwater Vehicles (UUVs) emerge as modern-day silent sentinels, navigating where humans cannot. Like space probes in the cosmic unknown, UUVs silently traverse the ocean’s depths, uncovering secrets in uncharted territories. To echo the spirit of space exploration, these technological marvels invite us to ‘boldly go where no one has gone before.’ The parallels between the cosmos and the underwater realm lie in their vastness and unexplored intricacies.

Known as the “Silent Observers of the Deep,” UUVs redefine maritime operations with their autonomous capabilities. Ranging from compact gliders to robust remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), these unmanned vehicles surpass human limitations, enabling unprecedented exploration and discovery. Echoing T S Eliot’s timeless words, “We shall not cease from exploration,” UUVs also call for maintaining the delicate balance of marine ecosystems.

Strategic experts, particularly in India, view the undersea domain as a perpetual game in sensitive littorals. Maritime domain awareness is a prevalent term, implying information superiority in the nautical realm. Adversaries are perceived as constantly seeking ways to outflank and outmanoeuvre defenders.

Beyond security concerns, maritime theorists highlight undersea geophysical and ecological phenomena affecting humans. Enhancing awareness beneath the waves is seen as a way to mitigate the impact of natural forces. A recent concept gaining attention is underwater domain awareness, suggesting technological advancements allow close monitoring of undersea activities.

Known as the “Silent Observers of the Deep,” UUVs redefine maritime operations with their autonomous capabilities. Ranging from compact gliders to robust remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), these unmanned vehicles surpass human limitations, enabling unprecedented exploration and discovery

Technical Challenges: Opaque Realms

Underwater domain awareness differs fundamentally from its counterpart over the seas. The undersea environment is opaque, lacking a defined path between transmission sources and targets. Unlike atmospheric sensors, undersea networks depend on sound-wave propagation, constrained by seawater density and temperature. This contrast poses challenges to range, endurance, and communication between sender and receiver.

The Indo-Pacific region plays a pivotal role in geopolitics, evolving into a theatre of intense security competition. Concerns centre around expanding strategic arsenals and disruptive naval technologies, particularly UUVs, contributing to maritime security destabilization and nuclear tensions. China, following the lead of the United States and Russia, actively develops UUVs to enhance its blue-water navy capabilities.

Chinese Presence and Concerns

The deployment of Chinese UUVs in the vast Indo-Pacific waters has the potential to disrupt the status quo. China’s increasing presence in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) and assertive stance in maritime disputes raise alarms. According to the Observer Research Foundation (ORF), China is expected to advance underwater vehicle development for forward operations. If China deploys UUVs in the IOR to detect Indian submarines, it could significantly increase instability in the region.

Analysts suggest that UUVs will significantly bolster Chinese long-distance targeting capabilities, reinforcing surveillance and reconnaissance capacities. China might employ UUVs for ‘hold-at-risk’ missions, particularly effective in blockading crucial chokepoints. These trends highlight China’s substantial investment in emerging technologies, reshaping traditional warfare approaches. In response, India must strengthen maritime security alliances, especially with the United States, Japan, and Australia. Additionally, India should focus on upgrading Anti-Submarine Warfare (ASW) capabilities and domestically developing UUVs to align with its security needs for subsurface naval operations.

Legal Complexities

While UAVs showcase cutting-edge technology, they also challenge ancient legal doctrines. The discourse revolves around whether a Maritime Autonomous Vehicle (MAV), defining both UUV and Unmanned Surface Vehicle (USV), qualifies as a ‘ship.’ The International Maritime Organization (IMO) defines Maritime Autonomous Surface Ship (MASS) as ‘a ship which, to a varying degree, can operate independently of human interaction.’ This definition, while broad, currently excludes underwater vehicles from IMO regulations, presenting legal implications for their rights in territorial seas and international chokepoints.

The lack of a universally accepted legal definition of a ‘ship’ becomes apparent when dealing with torpedo-shaped gliders like China’s ‘Seawing UUV’ or robotic sharks. These gliders, being ballasted vehicles, can traverse the water column vertically but may face challenges in positioning due to ocean currents. Instances of nations intercepting or capturing gliders further highlight the complexities surrounding these underwater vehicles.

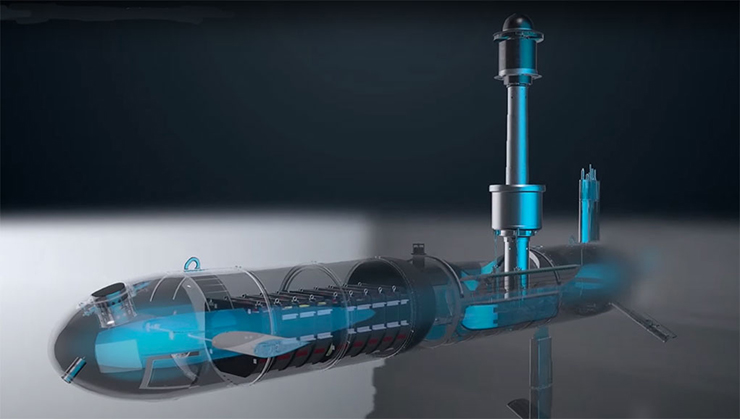

Evolution of XLUUVs

Nations are actively developing Extra-Large Uncrewed Underwater Vehicles (XLUUVs) with potential armament, a range of up to 3,000 nautical miles, and lengths of 30 meters. Long-term shipbuilding plans of naval forces include fleets of XLUUVs, envisioning capabilities for delivering multiple payloads over extended ranges. The legal and strategic considerations escalate with the United Kingdom’s announcement to employ an unarmed XLUUV for deterring and detecting attacks, adding complexity to international norms.

Difficulties in Defining a ‘Warship’

In the realm of maritime affairs, the historical definition of ‘warship’ faces reinterpretation with the advent of autonomous technologies. Traditionally defined by subordination to duly commissioned officers and crewed nature, fully autonomous MAVs pose challenges to this classification. The legal standing of MAVs in the law of armed conflict becomes crucial, determining their belligerent rights. The classification as ‘warships’ delineates their standing, impacting territorial sea rights during peacetime and responses to innocent passage violations.

China might employ UUVs for ‘hold-at-risk’ missions, particularly effective in blockading crucial chokepoints. These trends highlight China’s substantial investment in emerging technologies, reshaping traditional warfare approaches. In response, India must strengthen maritime security alliances, especially with the United States, Japan, and Australia

The determination of an MAV status as a ‘ship’ invokes the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). UNCLOS grants sovereign immunity to warships and government ships engaged in non-commercial service. Even if a MAV is deemed a naval auxiliary, it retains sovereign immunity, protecting it from arrest or detention by other nations. However, the classification of an MAV that is not explicitly categorised as a ‘ship’ remains unsettled in international law, with the United States asserting that sovereign immunity extends to MAVs.

From a maritime legal perspective, individual states retain the authority to determine whether a MAV qualifies as a ‘ship.’ This determination is based on a state’s discretion in registering vessels and assigning flags, similar to the categorisation of vessels as ‘warships.’ The extent to which other nations might contest these classifications remains an open question, raising concerns about the consistency and recognition of MAV classifications on the international stage.

Legal challenges extend beyond MAV classification, encompassing issues such as defining the legal status of remote operators and jurisdictional authority. States must grapple with questions about a remote operator’s responsibilities, especially when operating from a different state than the flag state and beyond the immediate vicinity of the vessel. The International Maritime Organization (IMO) is addressing some of these concerns in commercial shipping, but their applicability to military MAVs remains uncertain.

Advancements in Propulsion Technology

As a recently retired Navy Commander, the author has seen notable advancements in propulsion technology, particularly the brushless DC motor. These innovations contribute to enhanced propulsive efficiency, reduced noise, and downsizing of thrusters. When combined with cutting-edge UUV form factor design, such advancements lead to substantial improvements in the range and manoeuvrability of UUVs and autonomous weapon systems. The evolution of wave-powered UUV gliders introduces persistent acoustic surveillance capabilities, particularly valuable in Anti-Access/Area Denial zones.

International Humanitarian Law (IHL) Challenges

Intervention autonomy, a subset of UUV targeting parameters, allows a system to spatially align itself in the water concerning a close-proximity target. This technology, employing optical sensors and image processors, facilitates precise guidance of UUV weapons to specific points on a ship’s hull. The integration of such technologies raises ethical questions about the role of human intervention in decision-making processes for employing weapon systems.

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) defines Maritime Autonomous Surface Ship (MASS) as ‘a ship which, to a varying degree, can operate independently of human interaction.’ This definition, while broad, currently excludes underwater vehicles from IMO regulations, presenting legal implications for their rights in territorial seas and international chokepoints

In Anti-Access/Area Denial zones, adherence to IHL becomes crucial. The principle of distinction, ensuring differentiation between adversary vessels and civilian traffic, poses a significant challenge for unmanned systems. There is an undeniable need for human intervention in the decision-making process, emphasising the importance of upholding IHL targeting criteria related to civilians.

Need for Proactive Engagement

For the Indian Navy, a nuanced understanding of the laws of naval warfare is essential to navigate the legal implications of deploying armed XLUUVs. Recognising the practical challenges of having a human in the loop for autonomous submarines, there is a need for crewed vessels working in tandem with XLUUVs to ensure compliance with international legal obligations. It calls for proactive engagement with international law issues arising from the proliferation and demand for MAVs, emphasising the importance of adapting technology to established legal frameworks. The call for a new international law framework to encompass MAV functionalities and future capabilities reflects India’s commitment to the rules-based order.

-The writer is a former CDR (TDAC) in the Indian Navy with 21 years as a diverse Naval Aviator, including roles as a Seaking Pilot and RPAS Flying Instructor. Holding an MBA and certificates from Olin Business School and IIFT, he specialises in Product and Innovation Management, Aerospace Law, UAS, and Flight Safety. He leverages his skills to advance unmanned and autonomous systems, aiming to create value for Aatmanirbhar Bharat and Indian aviation.