The advancement initiatives of the Pakistan Air Force (PAF) throughout the current decade have been influenced by a trio of elements: Firstly, the clash with India that occurred in 2019. Secondly, the persistent conflict between Russia and Ukraine. Lastly, the enhanced access to sophisticated military capabilities provided by principal allies such as China and Turkey.

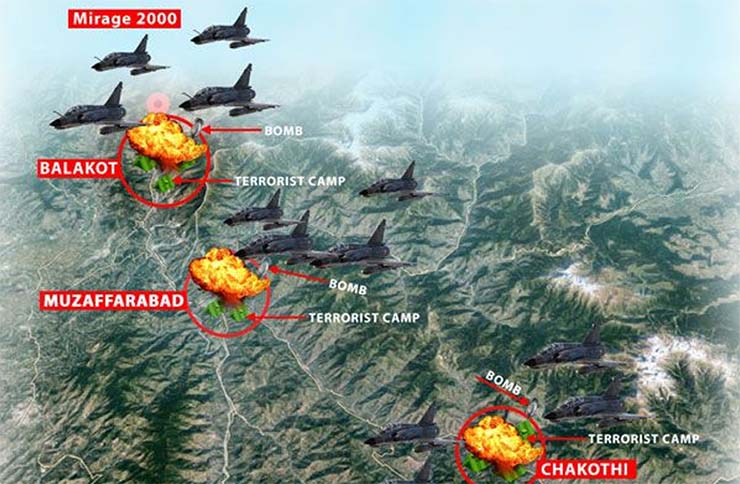

Among these factors, the primary trigger was the altercation with India, which precipitated Operation Swift Retort—a counterstrike by the PAF involving air operations over Indian territory in response to India’s earlier intervention in Balakot, Pakistan.

The incident in Balakot revealed certain operational deficiencies within the PAF, as well as broader strategic issues for Pakistan’s military. One key operational shortcoming was the ability of India to carry out long-range strikes from its own territory. Although the PAF possessed similar long-range weaponry, the peacetime execution of such an assault was unexpected and problematic.

Prior to 2019, Pakistan’s defence strategy hinged on the belief that its nuclear arsenal would serve as a deterrent against both nuclear and conventional assaults. The underlying logic was that any aggressive action could lead to an escalating conflict culminating in a nuclear confrontation and, consequently, Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD). The presence of nuclear weapons was intended to act as a shield against Indian military intrusions.

India’s actions not only challenged the presumed protection provided by Pakistan’s nuclear capabilities but also raised a new concern: the possibility of further ‘testing’ actions. Pakistan perceived that if the PAF had not reacted to the Balakot incursion with Operation Swift Retort, it might have opened the door to more frequent Indian strikes, potentially reaching further into Pakistani territory. This could lead to a broader sense of vulnerability and turmoil, particularly along the border regions of Azad Kashmir and the Northern Areas.

Pakistan perceived that if the PAF had not reacted to the Balakot incursion with Operation Swift Retort, it might have opened the door to more frequent Indian strikes, potentially reaching further into Pakistani territory

Given that nuclear deterrence was ineffective against such tactics, Pakistan recognised the need to enhance its conventional military strength across its army, navy, and air force. In essence, Pakistan started to prioritise conventional deterrence despite facing economic challenges and financial instability.

For the PAF, adopting a stance of conventional deterrence would mean expanding on the approach used in Swift Retort, which stands as its most significant air operation thus far. Swift Retort utilised a combined force of around 12 to 18 fighter jets, supplemented by Airborne Early Warning and Control (AEW&C), Electronic Attack (EA), and Electronic Countermeasures (EA/ECM) support. The operation was viewed as a triumph by the PAF, as it not only showcased the capability for counter-action but allegedly inflicted more substantial damage on India compared to the IAF’s incursion at Balakot. For instance, during the engagement, the IAF reportedly lost a MiG-21bis and a Mi-17 helicopter, and as per PAF’s assertions, a Su-30MKI fighter jet was also downed.

This portrayal of events, positioning Swift Retort as a strategic success and underscoring the PAF’s retaliatory prowess, formed the narrative presented to the Pakistani populace. It emphasised the operation’s effectiveness in causing more significant damage to the Indian Air Force than what was sustained during the Balakot strike, thereby bolstering national confidence in Pakistan’s conventional military capabilities amidst regional tensions. However, the details regarding the impact on the ground in Balakot, particularly the consequences for the militant outfits reportedly targeted in the strike, were not highlighted in the public discourse.

If Swift Retort is to be deemed a benchmark for operational success, then it is incumbent on the PAF to prove that it can execute operations akin to Swift Retort on a larger scale, whether back-to-back or even simultaneously. Should India recognise that any transgressions into Pakistani territory could trigger reprisals that are just as damaging—if not more so—it might deter future military ventures. Hence, there is a pressing need for the PAF to substantially advance its offensive capabilities.

A robust response mechanism constitutes just a part of the broader conventional deterrence strategy. The PAF has also focused on enhancing its ability to prevent enemy incursions. By bolstering its area-denial tactics, the aim is to thwart any incursion before it inflicts harm, thereby reducing the necessity for retaliation. Additionally, if India faces a heightened likelihood of unsuccessful missions, it could be discouraged from initiating aggressive manoeuvres to begin with.

Swift Retort utilised a combined force of around 12 to 18 fighter jets, supplemented by Airborne Early Warning and Control (AEW&C), Electronic Attack (EA), and Electronic Countermeasures (EA/ECM) support. The operation was viewed as a triumph by the PAF, as it not only showcased the capability for counter-action but allegedly inflicted more substantial damage on India compared to the IAF’s incursion at Balakot

The PAF’s air combat strategy for the remainder of the 2020s is cantered around two primary objectives: establishing effective area-denial defences and maintaining the capacity for extensive air operations. To achieve these goals, the PAF is pursuing advancements across seven key domains:

- Phasing out aging aircraft and systems

- Adopting a comprehensive strategy for area-denial

- Improving both tactical and strategic awareness

- Integrating UAV technology into offensive operations

- Enhancing capabilities for air mobility and logistical support

- Updating the curriculum for advanced air combat training

- Forming specialised units dedicated to offensive missions

1. Phasing out aging aircraft and systems

In a promotional video from January 2024, the PAF announced through Air Headquarters (AHQ) a “strategic move to retire outdated equipment.” Visuals included the Dassault Mirage III and 5, Chengdu FT-7P, the Karakoram Eagle (KE) AEW&C planes, and the CN-235 light transport aircraft. The overarching plan for the PAF is to withdraw aging planes from service and, particularly in the realm of specialised mission aircraft, to streamline its assortment of fleets.

Fighter Aircraft: The PAF’s efforts to retire and update its fleet of F-7P, FT-7P, F-7PG, and Mirage III/5 aircraft align with earlier projections. Back in 2016, the PAF had already set a goal to replace around 190 of its older fighter jets by 2020. The then-serving Chief of Air Staff, Air Chief Marshal Sohail Aman, underscored the PAF’s ambition to sustain a fighter fleet of approximately 400 aircraft. This target was aimed at achieving a ratio of 1:1.35 to 1:1.75 in comparison to the Indian Air Force’s strength.

Explaining Fighter Aircraft Ratios: In simple terms, the PAF (Pakistan Air Force) had set a goal to have a certain number of fighter jets compared to how many the IAF (Indian Air Force) has. When they say a ratio of 1:1.35 to 1:1.75, they mean that for every 1 fighter jet the PAF has, the IAF would have between 1.35 to 1.75 jets.

So, if the PAF has 100 fighter jets, they want to make sure that the IAF has between 135 and 175 jets, not more. This is a way for the PAF to measure their strength against the IAF and ensure they have enough planes to be competitive, even though they might have fewer planes overall. The goal is to maintain a balance so that the PAF has a strong enough air force to defend itself and its interests.

The recent promotional content indicates that the PAF is actively progressing in updating its fighter fleet. The video did not provide specific deadlines, yet it hinted at a transition away from the older F-7 and Mirage III/5 series potentially occurring within a relatively short span—possibly within the next three to five years, or by 2030 at the latest. The replacement fleet is set to include the J-10CE and the JF-17C (Block-III) models, which will be utilised in a strategic high-low combination to ensure operational effectiveness. At present, the PAF operates 20 J-10CEs and 30 JF-17Cs. It is anticipated by analysts that the PAF will continue to expand its inventory with more units of these aircraft types throughout the decade.

In November 2023, there were reports that the PAF was in discussions with the Aviation Industry Corporation of China (AVIC) concerning the acquisition of an undisclosed number of Hongdu L-15Bs to fulfil their lead-in fighter trainer (LIFT) requirements. The PAF had been in search of a new LIFT since at least 2017, aiming to more effectively train its pilots for 4th and 4.5th generation aircraft such as the J-10CE, JF-17, and F-16. Initially, in 2015, the JF-17B was considered for this training role, but by 2017 the PAF had decided to explore a dedicated platform instead. Notably, the PAF specified that the new LIFT should include features such as an afterburning engine, a multimode radar, and a tactical data link (TDL).

The LIFT specifications of the PAF indicate the need for an aircraft with comprehensive combat capabilities. The L-15B meets this criterion effectively. It comes equipped with a passive electronically scanned array (PESA) radar system and supports the use of SD-10 beyond-visual-range (BVR) air-to-air missiles (AAMs). Additionally, it has the capability to utilise precision-guided bombs (PGBs) as well as laser-guided bombs (LGBs), and it is also compatible with various targeting pods and electronic countermeasures (ECM) pods.

Positioning Swift Retort as a strategic success and underscoring the PAF’s retaliatory prowess, formed the narrative presented to the Pakistani populace. It emphasised the operation’s effectiveness in causing more significant damage to the Indian Air Force than what was sustained during the Balakot strike, thereby bolstering national confidence in Pakistan’s conventional military capabilities amidst regional tensions

Passive Electronically Scanned Array (PESA) radars use a single transmitter and multiple receivers to scan a wide area without moving physically, improving tracking and detection. Active Electronically Scanned Array (AESA) radars use multiple small transmitters and receivers, offering even better performance, including faster scanning and harder detection by enemies.

The L-15B aligns with the operational context of the PAF’s primary combat aircraft. Moreover, the PAF might utilise these attributes for specific operations, particularly in internal security roles such as counterinsurgency (COIN) or point air defence.

Presently, the PAF’s inventory includes 20 J-10CEs, approximately 75 F-16A/B Block-15s and F-16C/D Block-52s, 30 JF-17Cs, 26 two-seater JF-17Bs, 62 JF-17 Block-IIs, and about 50 JF-17 Block-Is. This adds up to 263 fighters from the desired 400-strong fleet of 4th and 4.5th generation jets, indicating a shortfall of roughly 140 aircraft

Special Mission Aircraft: The decision to phase out the KE AEW&C came as a surprise. The KE, which entered service in 2009, combines the ZDK03 PESA radar with the Shaanxi Y-8F600 aircraft. It has played a crucial role in the PAF’s maritime missions, often participating in combined exercises with the Pakistan Navy (PN) and demonstrating compatibility with PN’s equipment.

It appears that the PAF is consolidating its airborne early warning and control (AEW&C) capabilities around the Saab 2000 Erieye system. Initially, the PAF intended to solely use the Erieye, but later expanded its fleet in the late 2000s with four KE units from China. After a terrorist attack on Minhas Air Base in 2012 destroyed three Erieye aircraft, the KE units became vital in maintaining AEW&C coverage for the PAF.

By 2016, the PAF had replenished its Erieye AEW&C fleet back to four units and expanded it in 2017 with an order for three more. A subsequent order for at least two more systems in 2020 resulted in deliveries stretching from 2020 to 2023, bringing the PAF’s total Erieye AEW&C count to nine.

To accommodate the expanded Erieye AEW&C fleet, the PAF might reallocate staff from the KE units to the newly acquired Erieye aircraft. Consequently, the PAF is expected to deploy multiple Erieye AEW&Cs within its Southern Air Command, assuming the maritime support duties previously undertaken by the KE in collaboration with the Pakistan Navy.

Additionally, the PN is enhancing its AEW capabilities with its new Sea Sultan LRMPA aircraft. These may incorporate AEW functions through their main search radars. Should the PN select the Leonardo Seaspray 7500 V2 radar—similar to the one on its RAS-72 Sea Eagle MPAs—it would benefit from an AESA system capable of tracking both airborne and maritime targets. While not as comprehensive as a specialised AEW&C system, the PN could integrate the AEW feature of its LRMPAs with the Erieye network using TDLs.

Opting for the Erieye confirms its compatibility with Link-17, the PAF’s proprietary TDL, as well as Link-16 and the PN’s NIXS TDL. The PAF could employ ready-made solutions like MilSOFT’s Mil-DLP to equip the Erieye with the capability to handle multiple TDLs at once. This interoperability allows seamless integration with platforms such as F-16s, JF-17s, and J-10CEs, without any technical barriers to connectivity.

Logistics Aircraft: The PAF seems to be retiring its fleet of four CN-235 light transport planes. Having not expanded the fleet since the initial acquisition in 2005, there has been no increase in the number of CN-235 units within the PAF.

The PAF’s disinterest in expanding its CN-235 fleet raises questions about its commitment to developing a light/tactical airlift capacity. It may have reassigned these duties to smaller planes such as the Piper M-600 or Beechcraft Super King Air. Alternatively, the CN-235 might not have been used as extensively in its designated role as initially planned, leading the PAF to seek replacements better aligned with their operational requirements.

With the CN-235 being phased out, it’s uncertain how the PAF intends to support its Special Operations Forces (SOF) missions. It’s possible that the PAF is choosing to enhance its Hercules fleet, potentially through the acquisition of former Belgian C-130H planes, to fulfil this role and expand its broader air logistics and transport capabilities.

2. Adopting a comprehensive strategy for area-denial

In 2019, the PAF primarily depended on its fighter aircraft to prevent hostile planes from entering and dominating its airspace. The role of surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) was minimal in its strategy, especially considering that its most extended range system then was the MBDA Spada 2000-Plus, with a range of only 20 kilometres.

Traditionally, the PAF utilised its SAMs for the defence of key sites rather than actively preventing or deterring incursions by enemy aircraft at or near its borders. Post-2019, while continuing to invest in its fighter fleet, the PAF also developed a more formidable ground-based air defence system (GBADS). The Air Headquarters (AHQ) may have taken inspiration from Ukraine’s effective employment of GBADS to counteract adversary air superiority, subsequently implementing a similar strategy to safeguard Pakistan’s airspace.

The PAF’s air combat strategy for the remainder of the 2020s is cantered around two primary objectives: establishing effective area-denial defences and maintaining the capacity for extensive air operations. To achieve these goals, the PAF is pursuing advancements across seven key domains

It should be mentioned that the PAF has laid the foundation for incorporating not only medium- and long-range SAM systems but also directed energy weapons and passive defence strategies. These advancements are presumably in response to the emerging threats posed by loitering munitions and drone swarms.

Multirole Combat Aircraft: Looking ahead, the PAF is set to only induct combat aircraft that are equipped with AESA radars, built-in ECM (Electronic Counter Measure) capabilities, helmet-mounted displays and sights (HMD/S), and are capable of deploying long-range air-to-air missiles (LRAAM) as well as high off-boresight (HOBS) air-to-air missiles (AAMs).

The PAF’s acquisition strategy for the coming years, extending potentially into the 2030s, is set to focus on a high-low combination of the J-10CE and the JF-17C/Block-III aircraft. Both jets will serve dual roles, engaging targets in the air and on the ground, with the JF-17C expected to take on the majority of stand-off weapon (SOW) usage in the short term. Together, these aircraft are poised to take over the duties from the aging F-7P/PG and Mirage III/5 fleets.

J-10CE Dragon: In March 2022, the PAF added the Chengdu J-10CE to its forces, furthering its goal to reinforce its F-16 and JF-17 squadrons with a ready-to-use fighter jet. Quwa media house confirmed the presence of 20 J-10CEs in the PAF’s line-up, supporting the details from a leaked contract with AVIC that reportedly included the purchase of 240 PL-15E long-range air-to-air missiles (LRAAMs).

The operation known as Swift Retort was a significant factor in the Air Headquarters’ (AHQ) decision to finalise the purchase, but the PAF had been in pursuit of a ready-to-use fighter since 2015. The original plan was to expand the F-16C/D fleet, with ambitions to reach at least 55 aircraft before the 2005 Kashmir earthquake redirected resources. Subsequent cooling of defence relations with Washington disrupted these plans, prompting AHQ to explore alternatives from Russia and China.

The J-10CE emerged as the most practical alternative to the F-16s, given the strong relationship between the PAF and China, and the compatibility of the J-10CE with the PAF’s current inventory of air-to-air munitions, such as the SD-10 and PL-5E missiles. The J-10CE’s systems were also compatible with those of the JF-17. Additionally, AVIC’s ability to deliver the first set of aircraft within just eight months of contract signing was remarkable, especially considering that the induction of brand-new aircraft typically spans 18 to 24 months.

JF-17B/C Thunder: Although the J-10CE is often the focal point of discussions, the PAF remains committed to the JF-17 program, particularly the newest variants, which include the two-seater JF-17B and the advanced JF-17C, also known as Block-III.

The PAF’s standard combat aircraft, the JF-17C, is equipped with an Active Electronically Scanned Array (AESA) radar, a helmet-mounted display and sight (HMD/S), and electronic countermeasures (ECM). The onboard KLJ-7A radar system can detect targets with a 5m2 radar cross-section (RCS) at distances up to 170 km, track up to 15 targets at once, and simultaneously engage four. It incorporates a Chinese-produced HMD/S, potentially the same type utilised by the PAF’s J-10CE, and is capable of using high off-boresight (HOBS) air-to-air missiles, along with the capability to deploy the PL-15E missile.

Although the JF-17B/C may not match the J-10CE in terms of aerodynamic prowess or operational range, the Thunder remains an effective option for defensive roles. Its affordability for large-scale procurement is bolstered by the PAF’s established infrastructure for operation, the ability for domestic production, and its relatively lower expenses.

The PAF initially planned to purchase 50 JF-17Cs but has so far only confirmed an order for 30. It appears that the PAF has divided its procurement between the JF-17C and the two-seater JF-17B. Notably, the JF-17B closely mirrors the JF-17C in terms of capabilities, including the adoption of a new fly-by-wire (FBW) control system, the ability to equip an AESA radar, among other enhancements. Consequently, the PAF has the opportunity to standardise its JF-17Bs with the JF-17C model, which would bring its total count of ‘advanced model’ JF-17s to 56.

L-15B: While there is active discussion about the J-10CE and JF-17B/C, the status of the L-15B within the PAF is less clear, as there has been no formal confirmation of the PAF’s interest in acquiring the aircraft. However, the L-15B has the potential to serve as a competent fighter, with the ability to employ the SD-10 long-range air-to-air missile. As such, it could prove to be a useful asset for internal security or for providing point air defence, complementing the existing fleet of J-10CE, JF-17C, F-16, and older JF-17 Block-I/II aircraft.

Surface-to-Air Missiles: The PAF has shifted its strategy for airspace denial, expanding beyond exclusive dependence on fighter jets. Instead, the introduction of surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) is set to enhance its initial defence capabilities against hostile air movements. In pursuit of this objective, the PAF has initiated investments in an array of SAM systems, encompassing both medium-to-long-range and long-range categories.

Historically, the PAF’s go-to SAM systems included the MBDA Spada 2000-Plus, the French Crotale 2000, and the handheld Mistral MANPADS. The PAF’s ground-based air defence systems (GBADS) were traditionally focused on protecting specific installations such as air bases and radar facilities, rather than on wide-area territorial defence.

Currently, the PAF views its ground-based air defence systems as essential components of its territorial defence strategy, designed to operate synergistically with its fighter aircraft. The revised PAF GBADS structure is characterised by a comprehensive, tiered approach that integrates long-range, medium-range, and short-range surface-to-air missiles, along with a mix of other defensive measures including directed energy weapons (DEWs) and electronic attack (EA) capabilities.

-To be continued…

-The writer is Aerospace & Defence Analyst. The views expressed are personal and do not necessarily carry the views of Raksha Anirveda