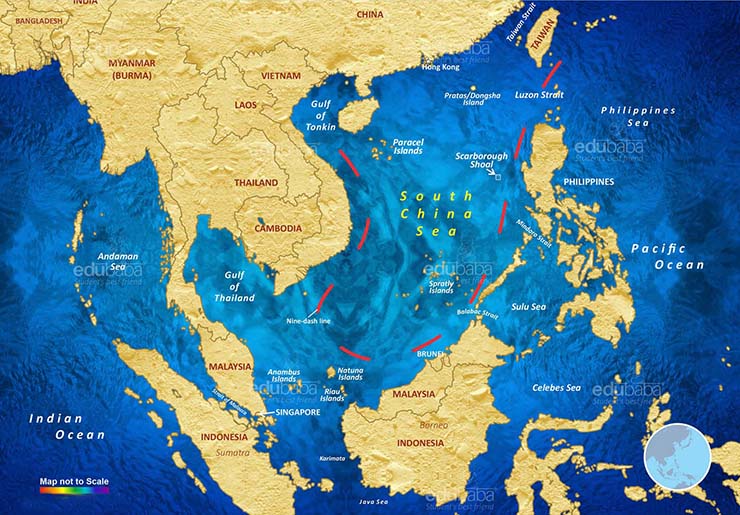

With a surface area of 8,00,000 sq km, the South China Sea is semi-enclosed, with 90 percent of its circumference bordered by land. Asia’s several influential countries, including the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei, Indonesia, Singapore, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, the People’s Republic of China (PRC), and Taiwan (the Republic of China), are situated along its littoral lines. Even though the South China Sea has been ignored internationally for decades, certain inferred rights over continental shelf delimitation have been based on acts of discovery and occupation. In the 1970s, oil exploration prospects became real, and the UNCLOS (UN Convention on the Law of the Sea) became the standard for delineating offshore jurisdictional boundaries for resource extraction as the legal aspects of the claims became more prominent for governments

Nevertheless, a recent stir surrounding the SCS surfaced during a joint statement issued by India and the Philippines on June 29, wherein Indian Foreign Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar and Filipino counterpart Enrique Manalo called on China to adhere to the 2016 arbitration award. In July 2016, an arbitration tribunal set up under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea ruled in favour of the Philippines, which had petitioned against China’s aggressive actions in the disputed oil-rich waters.

Consequently, there has been a flurry of commentary in the media speculating that India may shift away from its longstanding neutrality on territorial disputes in Southeast Asia. This is the first time New Delhi explicitly called on China to heed the arbitral tribunal’s 2016 ruling, despite India’s longstanding support for the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

History of claims surrounding the South China Sea

Historically, China has claimed sovereignty over the South China Sea. During the Sung dynasty (12th century), and records of Chinese navigators during the Qing dynasty (18th century) contain references to the Chinese case. It is important to note, however, that the use of coastal points as implied references for the Spratly Islands presents significant problems of authenticity and accuracy. In international discussions of the Spratlys, Taiwan’s claims mirror those of the PRC and evidence suggests both governments are trying to coordinate their positions on Chinese claims.

A recent stir surrounding the South China Sea surfaced during a joint statement issued by India and the Philippines on June 29, wherein Indian Foreign Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar and Filipino counterpart Enrique Manalo called on China to adhere to the 2016 arbitration award. Consequently, there has been a flurry of commentary in the media speculating that India may shift away from its longstanding neutrality on territorial disputes in Southeast Asia

A longstanding historical connection to the islands is the basis for Taiwan’s claim. As a result, Taiwan’s sovereignty claims are deficient, just like those of the PRC, in that discovery of and intermittent contact with scattered island formations is not sufficient to establish legal title. As a result of historical activities during the Nguyen dynasty (17th to 19th centuries), Vietnam claims the South China Sea islands legally. The government compiled and presented historical maps and evidence to support Vietnam’s claims in two white papers, Vietnam’s sovereignty over the Hoang Sa and Trung Sa Archipelagos, issued in 1979 and 1982.

Since Vietnam fails to differentiate between the Spratly and Paracel islands, its evidence for asserting title is weakened. It has been difficult to assess the lawfulness and propriety of the claims because they are treated generically, without being geographically distinguished. Considerable doubts also arise over the authenticity and accuracy of the historical record itself.

Recent developments on the SCS front

The South China Sea (SCS) has become increasingly contested since the United States launched a warship near the disputed Paracel Islands. Following this, US President Joe Biden and his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping held a summit, their second, in San Francisco on November 15, on the sidelines of the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation conference. Their goal was to revive a bilateral relationship that is at its lowest point since Washington and Beijing established diplomatic relations in 1979. To prevent potentially catastrophic miscalculations, the most consequential outcome was the decision to restore military-to-military communications between the two nuclear weapons states. Under the Military Maritime Consultative Agreement, which was signed in 1998, the respective defence forces will resume regular information exchange. However, after Nancy Pelosi’s controversial visit to Taiwan in August 2022, the first visit by a US House Speaker in 25 years, these channels were closed. But with China seeking Taiwan’s reunification with the mainland, Taiwan’s status remains a bone of contention between the world’s biggest superpowers. Under the Taiwan Relations Act, Washington recognises Taiwan as part of China, but does not endorse it as a legitimate government.

Geopolitics is not the only factor influencing South China Sea norms and rules. Countries in the Indo-Pacific have a legitimate interest in maintaining maritime peace and stability. Many regard the UNCLOS principles of freedom of navigation, overflight, and unhindered commerce as essential for regional trade. As a firm proponent of a rules-based maritime order, India has sought to expand its maritime presence in the Indo-Pacific region, including in the Western Pacific, where Indian naval forays and operational exercises have grown incrementally.

US President Joe Biden and his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping held a summit in San Francisco on November 15, on the sidelines of the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation conference. Their goal was to revive a bilateral relationship. To prevent potentially catastrophic miscalculations, the most consequential outcome was the decision to restore military-to-military communications between the two nuclear weapons states

India has also developed close ties with Southeast Asian countries such as the Philippines, which recently signed a contract with New Delhi for the supply of three batteries of the BRAHMOS missile. Vietnam, another of India’s close partners in the region and a beneficiary of a USD 100 million line of credit to procure high-speed patrol boats, is set to receive a stealth warship, the INS Kirpan, from the Indian navy.

India’s stand:

There is no dispute between India and China in the SCS and India is present in the SCS for its own economic interests, including its energy security needs. India, however, has had to reevaluate its approach to the South China Sea as China’s ability to decide and expand its role has increased.

Chinese account:

Although China claims nearly all of the South China Sea, including the Paracel Islands, Taiwan, Philippines, Brunei, Malaysia and Vietnam also claim portions of the region. According to the Chinese government, the US warship violated China’s sovereignty and caused harm to regional peace by entering Xisha (Paracel) island’s waters without permission.

USA’s account:

In light of competing claims by China and other governments, the USA argues that such exercises are in line with international law. US efforts are aligned with China’s continuous assertion in the SCS.

Other Issues:

The South China Sea has an unclear geographic scope. There is disagreement over the dispute resolution mechanisms. A lack of legal status for the Code of Conduct (COC) complicates the multifaceted matter. Further, the different histories of distant, largely uninhabited ocean archipelagos convolute the issue. The South China Sea remains a vital geo-strategic link between North East Asia’s seaborne trade and the rest of the world, particularly through the chokepoints of the Taiwan Strait in the north and the Strait of Malacca in the south. While the South China Sea is a very important commercial and military sea route, it also provides living and mineral resources to the littoral states. Almost half of the protein requirements of the population bordering the South China Sea are met by the region’s abundant fishing activities. And, over the past two decades, competing claims to island territories, maritime and seabed jurisdictions, and access to fisheries have thrown governments into a tangled nexus of conflicts and rivalries.

Why India should consider expanding its presence in SCS?

In response to China’s threatening tactics in the South China Sea, India has started internationalising disputes in the Indo-Pacific region as part of its Act East Policy. The Indian Navy has also deployed with Vietnamese forces in the South China Sea to protect sea lanes of communication (SLOCs), depriving China of any space for assertiveness. Moreover, India is a lynchpin of the Indo-Pacific narrative and a member of the Quad Initiative (the US, Japan, Australia, and India). China views these initiatives as a containment strategy.

While India should not venture into the South China Sea waters for security reasons, it should do so for strategic reasons. India is expanding its maritime vision by improving relations with the Pacific Island countries and can follow suit for maritime vision in the South China Sea for combating piracy, trafficking of goods, and terror activities. This will in turn facilitate trade relations between India, China and the littoral states

While India should not venture into the SCS waters for security reasons, it should do so for strategic reasons. The reasons why India is present in far-off seas are neither unique nor uncommon. Under UNCLOS, all countries are entitled to free navigation on the high seas, in their Exclusive Economic Zones, and even in their territorial waters for ‘peaceful reasons’. Over 80 per cent of India’s trade depends on sea lines of communication. While the 2015 government figure of over 55 per cent of trade passing through the SCS waters requires revision now, India finds strong market and trade synergies with Japan, South Korea, and ASEAN as much as it does with China. India also needs to protect commercial shipping vessels in Southeast Asian waters infested with piracy and trafficking. The Indian Navy’s recent visits to faraway African and Latin American countries have showcased its diplomatic approach and naval capabilities to traverse and sustain in faraway waters. India is expanding its maritime vision by improving relations with the Pacific Island countries and can follow suit for maritime vision in the SCS for combating piracy, trafficking of goods, and terror activities. This will in turn facilitate trade relations between India, China and the littoral states.

Additionally, the post-COVID scenario has underscored the importance of resilient supply chain mechanisms. Thus, India and China are also jointly exploring two oil exploration blocks off the coast of Vietnam, 127 and 128. Most importantly, India believes that global commons, such as maritime domains, should be free, open, and inclusive when used. Furthermore, India commits to maintaining a fair maritime order and to resolving any disputes peacefully. In this context, India should be vocal in positioning its maritime interests both unilaterally and multilaterally in the SCS.

–The writer is a professional and experienced writer having worked with multiple organisations. He is a keen observer of global affairs, geopolitics and how it affects the world order. The views expressed are of the writer and do not necessarily reflect the views of Raksha Anirveda