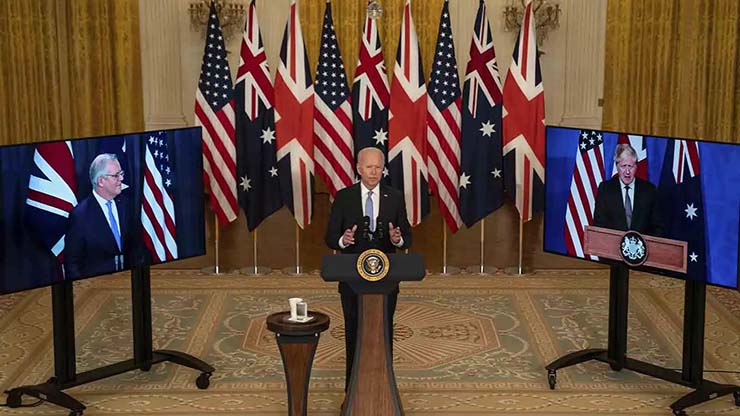

The announcement of AUKUS, the recently established Anglo-Saxon trilateral between Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States of America in September 2021 took the world by surprise and generated a great deal of discussion and debate on its likely impact on future developments in the Indo-Pacific region. It was more the nature of the announcement that led to this surprise in some quarters and concern in others because bilateral, trilateral and minilateral arrangements are not unusual in the region and are in fact seen as constructive mechanisms for building collective synergy on various issues. Just one year ago, in October 2020, Australia, France and India had also established a trilateral; similarly there is already an Australia-Japan-USA trilateral.

The formation of AUKUS, however, seemed to be different in the reactions it evoked from various quarters. From a Quad perspective, it was welcomed by the other two Quad members, Japan and India, both of whom believed it will strengthen the effort at ensuring a Free and Open Indo-Pacific. ASEAN, whose centrality has been acknowledged by the Quad, was guarded in its response but did not criticise it. China, not surprisingly, indulged in its usual shrill rhetoric, which is par for the course. For the United Kingdom, it was a significant step in its ‘tilt’ to the Indo-Pacific. This ‘tilt’, which is part of Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s vision of a Global Britain, is an important element of the UK’s ‘Integrated Review’.

France, which is an important player in the Indo-Pacific with more than 90% of its EEZ located in this region and a substantial and permanent naval presence and also the only country to have appointed an Ambassador to the Indo-Pacific, reacted badly. It publicly stated that it had been ‘stabbed in the back’ and recalled its Ambassadors to both Canberra and Washington. However, geopolitical considerations in the region should assuage these hurt feelings over time and the larger picture will prevail.

This show of displeasure by France had less to do with the geopolitics of the Indo-Pacific and everything to do with the cancellation of the Australian contract with the Naval Group of France for the indigenous construction of 12 conventional diesel-electric submarines of the Short-Fin Barracuda class (derived from the new French Barracuda class SSNs). This was the largest defence order ever received by France; it began as a AUS $50 billion contract, had already skyrocketed to an estimated AUS $90 Bn with not even a final design being ready and would have continued to grow till the last of the submarines was commissioned around 2050. The programme was already facing severe criticism within Australia and the clamour for its cancellation was growing both in the parliament and in the media. For France this was a double whammy – not only had it lost its most lucrative contract but also lost a major source of revenue that helps fund its own nuclear submarine programme; France operates an all-nuclear submarine fleet and builds/designs conventional submarines only for export.

What perhaps added insult to injury was the Australian decision to build eight nuclear powered attack submarines with assistance from the UK and the USA in lieu of the 12 French-designed submarines; as Australia’s submarine partner and an established nuclear submarine building nation, France perhaps felt that it could have supported Australia’s foray into nuclear powered submarines. In fact, many believe that the decision to develop a new design based on the French Barracuda class SSN was perhaps taken keeping a future nuclear option in mind though there is no official statement supporting such an assumption. It is amazing that Australia was able to keep such an important decision, which also involved two external partners and reportedly was 18 months in the making under wraps. However, if one were to read between the lines in Australia’s recent defence strategy documents, this development was not entirely unexpected.

However, the French pique notwithstanding, this development also garnered extra attention due to Australia’s decision to go nuclear and indicated a giant leap of faith by Australia as it currently has very rudimentary nuclear expertise in the country, either civilian or military. It has only one 20MW swimming pool nuclear research reactor in the country called OPAL (Open Pool Australian Lightwater Reactor) and continues to debate the efficacy of nuclear energy for civilian applications.

In the last couple of years Australia has shown a marked change in approach to the region. It has positioned itself as an Indo-Pacific power and has shed its reticence on calling out China for its economic intimidation even at the cost of sanctions. China in its typical fashion has been using its wolf warrior diplomacy to pressurise Australia through an orchestrated campaign using both academia and public figures to subvert the strategic narrative within the country.

This decision has also raised concerns about China upping the ante in its submarine programme, which could compel other nations to also doing the same leading to a possible submarine arms race in the region. However, seen from another perspective, it is actually China that is generating the arms race with its ambitious shipbuilding programme (20-odd blue water capable ships and submarines being added every year) despite already having the largest navy in the world by numbers, its maritime belligerence and its clearly stated intention to alter the regional status quo.

Submarines constitute the cutting edge of a nation’s offensive maritime power. They have the ability to shape the maritime battlespace. For smaller navies, they are not only the most effective sea denial assets but even offer limited sea control against a more powerful adversary. In recent years, there has been frequent comment on the proliferation of submarines in the Indo-Pacific, which is set to further grow with most navies either augmenting their present force levels or aspiring to build their submarine capability. While the focus will remain on conventional diesel-electric submarines, the next two decades could see a similar increase in nuclear attack submarines (SSN) in the region.

SSNs are propelled by nuclear power but are armed with conventional weapons. They are very powerful platforms and can either singly, or as part of a larger Task Force, shape the maritime theatre to advantage with their ability to do high speeds underwater, their stealth characteristics and their powerful weaponry consisting of heavyweight torpedoes and cruise missiles that can neutralise targets on land and sea at considerable ranges with pinpoint accuracy.

Currently, six navies in the world operate SSNs. These are the five permanent members of the UN Security Council – USA, Russia, UK, France and China. India, the sixth, has been leasing SSNs from Russia while it pursues its indigenous programme to build this capability. Its tryst with nuclear submarines began with the lease of a Charlie class SSN (commissioned as INS Chakra) from the erstwhile Soviet Union for three years from 1988 to 1991. In 2012, it leased an Akula-2 class submarine from Russia for 10 years, which was also commissioned as INS Chakra. This submarine was returned earlier this year and had provided the country and the Navy valuable experience and expertise in operating, supporting and maintaining these complex platforms. India is likely to acquire another one, or possibly two SSNs on lease from 2025 onwards for another 10 years and further consolidate its skills..

All these six countries have mature civilian nuclear programmes and well established nuclear safety procedures and practices in place. Australia, on the other hand, has little or no experience with nuclear power. Hence the SSN challenge for Australia is considerable.

China currently has a force level of six SSNs of the Type 093 class that are deployed regularly in the Indian Ocean. Analysts believe that these submarines lag their western counterparts and are perhaps a generation or so behind in technology. However, the effort being put by China to harness contemporary and emerging technologies for military applications leads one to confidently predict that the next class of SSNs being developed in China, designated the Type 095, will be on par with global standards. China has articulated its intent to double its nuclear submarine fleet by 2030, which will lead to an increased presence of Chinese SSNs in the Indo of the Indo-Pacific i.e, the Indian Ocean and should be of concern to India.

In the next decade or so, it can be safely assumed that amongst the other SSN-operating navies, US and Russian SSNs will be a permanent presence in the Indo-Pacific whereas the French and the British with a limited inventory will deploy theirs periodically. It is therefore important that resident navies develop their own capabilities to defend their maritime interests in the region.

India has embarked on an indigenous programme to build six SSNs for which clearance at the apex level of government is awaited. The Cabinet Committee on Security (CCS) had approved a capability study in 2015 that has been successfully completed so the nod for fast tracking the programme should follow soon. India has already developed its indigenous capability to build nuclear powered submarines with its nuclear powered ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) programme and the successful deployment of INS Arihant, which is the first of these. The second of the class, named Arighat, is at an advanced stage of trials and two more are reportedly under construction.

SSNs vary from SSBNs in the nature of their deployment but the fundamental nuclear technology and the principles of nuclear submarine construction remain the same. Assuming that the CCS grants early approval to the programme, and that it should, considering the urgency of the requirement, it will still take more than a decade and a half at the very least for the first of these to be combat ready. Subsequent submarines will follow at periodic intervals after that and the overall programme could take 25 years or more to complete. These timelines are not unusual as even experienced nuclear submarine building countries take over a decade to operationalise a new design.

Australia’s recent announcement makes it the only other Indo-Pacific power besides India that is now committed to building a SSN capability. It will probably obtain a US or British SSN on lease (more likely the former since the latter are limited in numbers) to begin with, and that itself could take five years or more and will be operated with oversight from the host country. Operating a nuclear submarine requires a deep knowledge of the complexities of nuclear power and propulsion. As mentioned earlier, Australia has little or no experience with civilian nuclear power and may also begin to foray into that arena. Creating the required infrastructure and generating the right resources for operating, supporting and maintaining nuclear submarines even with external support are challenging tasks. Indigenous construction of these submarines is still many years away and once begun, could take up to 15-20 years for the first one to become operational. Till then, the country will have to make do with leased SSNs while gaining the requisite expertise.

There has been speculation that South Korea will soon embark on an indigenous SSN programme. There are views, both for and against in the country though media reports indicate that the next class of submarine, expected to displace more than 4,000 tons, could be nuclear-propelled. South Korea is a leading nuclear energy producer and has the technology as well as the submarine building skills to undertake the task. Significantly, it recently fired a submarine launched anti-ship cruise missile and is arming its latest KS-III conventional submarines with this capability.

Japan’s constitutional limitations preclude it from considering the nuclear submarine option and it is unlikely that this will be reversed soon. However, given the prevailing security scenario in the western Pacific and the growing threat to its maritime interests from its belligerent maritime neighbour, the decision may have to be reviewed sooner rather than later. As a global leader in many advanced submarine technologies and with a mature nuclear industry, which unfortunately has been under a cloud for some time, it has the wherewithal to develop a SSN capability indigenously should it choose to do so.

North Korea, the shrillest amongst all with its rhetoric, is unlikely to be able to develop a SSN capability. It has been firing a range of missiles from its submarines but its platforms are antiquated.

Amongst other nations east of the Malacca Straits, it is unlikely that any other country will build or operate SSNs. Singapore, Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam and Malaysia will continue operating conventional submarines and The Philippines may become the next entrant to the conventional submarine club.

In the Indian Ocean, there is little possibility that any country other than India will have the capability or the resources to build SSNs in the foreseeable future. Pakistan, in its effort at obtaining military parity with India may pressurise China to lease it a SSN but whether China will oblige unless of course it sees a benefit for itself in doing so is a moot point. Iran and Israel are suspected to have tactical nuclear weapons capability as does Pakistan, which will remain a threat given the political volatility in these nations. Bangladesh, Myanmar and South Africa are the only other submarine operating navies in the Indian Ocean and none is likely to go for SSNs.

In a time span of the next 15 years or so, Chinese naval activity in the Indian Ocean will increase exponentially. With a likely force level of three to four aircraft carriers by the end of this decade, at least one Carrier Battle Group will be permanently deployed in the Indian Ocean. It is understood that the jetty at the Chinese naval base in Djibouti is being extended to berth an aircraft carrier. China is also arming Pakistan with four Type 054 destroyers, the first of which was commissioned on November 08 this year, and eight conventional submarines. Hence, India, which has rarely been challenged in the western Indian Ocean, could find its energy security and trade vulnerable to a Chinese and Pakistani naval presence at Djibouti, Gwadar and off the Straits of Hormuz. Indian SSNs deployed in the region with a commensurate surface and air capability could effectively counter this vulnerability.

As far as India is concerned, its relationship with Australia is on an upward trajectory. Frequent interaction at the highest levels has been the order of the day in the recent past and India also has a 2+2 dialogue with Australia. Hence a presence of SSNs from Australia and other like-minded nations in the eastern Indian Ocean would be a welcome move to effectively counter a Chinese blue water presence in the South-eastern Indian Ocean region and will ease the pressure on India in safeguarding its own maritime interests besides ensuring a Free and Open ‘Indo’ in the Indo-Pacific .

– The author is a Vice-President, Indian Maritime Foundation. The views expressed are personal and do not necessarily reflect the views of Raksha Anirveda

-The author is Vice President, Indian Maritime Foundation. The views expressed are personal and do not necessarily carry the views of Raksha Anirveda