In 326 BCE, a formidable European army invaded India. Led by Alexander of Macedon it comprised battle hardened Macedonian soldiers, Greek cavalry, Balkan fighters and Persians allies. Estimates of the number of fighting men vary – from 41,000 according to Arrian to 120,000 as per the account of Quintus Curtius. (1)

Their most memorable clash was at the Battle of Hydaspes (Jhelum) against Porus, the ruler of the Paurava kingdom of western Punjab. For more than 25 centuries it was believed that Alexander’s forces had defeated the Indians. Greek and Roman accounts say the Indians were bested by the superior courage and stature of the Macedonians.

More than a thousand years after Alexander’s death, the mythmaking reached absurd and fantastic proportions with the arrival of a new genre known as the Greek Alexander Romance (2), a fictional account of Alexander’s Asian campaigns composed of a conglomeration of the rumours surrounding his rule. The destruction of the Persian Empire and the defeat of the Indian kingdoms were the highlights that drove the popularity of the Alexander Romance in Europe. A version of this story was included in the Koran in which Alexander is called Dhulkarnain.

During the colonial period, British historians latched on to the Alexander legend and described the campaign as the triumph of the organised West against the chaotic East. Although Alexander defeated only a few minor kingdoms in India’s northwest, in the view of many gleeful colonial writers the Greek conquest of India was complete.

In reality much of the country was not even known to the Greeks. So handing victory to Alexander is like describing Hitler as the conqueror of Russia because the Germans advanced up to Stalingrad.

Zhukov’s View of Alexander

In 1957, while addressing the cadets of the Indian Military Academy, Dehra Dun, the great Russian general Georgy Zhukov(3) said Alexander’s actions after the Battle of Hydaspes suggest he had suffered an outright defeat. In Zhukov’s view, Alexander had suffered a greater setback in India than Napoleon in Russia. Napoleon had invaded Russia with 600,000 troops; of these only 30,000 survived, and of that number fewer than 1,000 were able to return to duty.

If Zhukov compared Alexander’s campaign in India to Napoleon’s disaster, the Macedonians and Greeks must have retreated in an equally ignominious fashion. The World War II commander would recognise a fleeing army if he saw one; he had chased the Germans over 2000 km from Stalingrad to Berlin.

No Easy Victories

Alexander’s troubles began as soon as he crossed the Indian border. He first faced resistance in the Kunar, Swat, Buner and Peshawar valleys where the Aspasians (Iranian Aspa, Sanskrit Asva = horse) and Assakenoi (Sanskrit Asvakas or Asmakas, perhaps a branch of, or allied to, the Aspasioi), challenged his advance. Although mere specks on the map by Indian standards, they did not lack in courage and refused to submit before Alexander’s killing machine.

The Aspasians hold the distinction of being the first among the Indians to fight Alexander. The Roman historian Arrian writes in ‘The Anabasis of Alexander’ that with these people “the conflict was sharp, not only from the difficult nature of the ground, but also because the Indians were….by far the stoutest warriors in that neighbourhood”. (4)

The intensity of the fighting can be measured from the fact that during the siege Alexander and his two of leading commanders were wounded. Alexander was hit by a dart which penetrated the breastplate into his shoulder. But the wound was only a slight one, for the breastplate prevented the dart from penetrating right through his shoulder.

In the end, the guile and superior numbers of Alexander’s army won the day. The Macedonians captured 40,000 men and 230,000 oxen, transporting the choicest among the latter to their country for use as draft animals.

Alexander next attacked the hill state of Nysa, which probably occupied a site on the lower spurs and valleys of the Koh-i-Mor. It was governed by a body of aristocracy consisting of 300 members, Akouphis being their chief. The Nysaens readily submitted to the Macedonian king, and placed at his disposal a contingent of 300 cavalry. According to Rama Shankar Tripathi(5), the Nysaens claimed descent from Dionysius. “This gratified the vanity of Alexander, and he therefore allowed his weary troops to take rest and indulge in Bacchanalian revels for a few days with their alleged distant kinsmen.”

Greek Guile Defeats Massaga

Alexander’s next nemesis was the Assakenoi who offered stubborn resistance from their mountain strongholds of Massaga, Bazira and Ora. Realising the gravity of this new threat from than West, they raised an army of 20,000 cavalry and more than 30,000 infantry, besides 30 elephants.

The fighting at Massaga was bloody and prolonged, and became a prelude to what awaited Alexander in India. On the first day after bitter fighting the Macedonians and Greeks were forced to retreat with heavy losses. Alexander himself was seriously wounded in the ankle. On the fourth day the king of Massaga was killed but the city refused to surrender. The command of the army went to his old mother, which brought the entire women of the area into the fighting.

The fighting at Massaga was bloody and prolonged, and became a prelude to what awaited Alexander in India. On the first day after bitter fighting the Macedonians and Greeks were forced to retreat with heavy losses. Alexander himself was seriously wounded in the ankle. On the fourth day the king of Massaga was killed but the city refused to surrender. The command of the army went to his old mother, which brought the entire women of the area into the fighting.

Realising that his plans to storm India were going down at its very gates, Alexander called for a truce. Typical of Indian kingdoms right through history, the Assakenoi agreed to their eternal regret. While 7,000 Indian soldiers were leaving the city as per the agreement, Alexander’s army launched a sudden and sneaky attack. Arrian writes: “Undaunted by this unexpected danger, the Indian mercenaries fought with great tenacity and “by their audacity and feats of valour made the conflict, in which they closed, hot work for the enemy”.

When many of the Assakenoi had been killed, or were in the agony of deadly wounds, the women took up the arms of their fallen men and heroically defended the citadel along with the remaining male soldiers. After fighting desperately they were at last overpowered by superior numbers, and in the words of Diodoros “met a glorious death which they wouId have disdained to exchange for a life with dishonour”. (Hindu women like Rani Padmini, who preferred to jump into the fires of jauhar rather than become captives, can trace their tradition of self-sacrifice and valour to antiquity.)

After the fall of Massaga, Alexander advanced further, and in the course of a few months’ hard fighting captured the important and strategic fortresses of Ora (where a similar slaughter followed), Bazira, Aornos, Peukelaotis (Sanskrit = Pushkaravati, modern Charsadda in the Yusufzai territory), Embolima and Dyrta. (Due to the peculiar Greek orthography most of these cities are now impossible to identify or decipher.)

However, the fierce resistance put up by the Indian defenders had reduced the strength – and perhaps the confidence – of the until then all-conquering Macedonian army.

Faceoff at the River

In his entire conquering career Alexander’s hardest encounter was the Battle of Hydaspes, in which he faced king Porus of Paurava, a small but prosperous Indian kingdom on the river Jhelum. Porus is described in Greek accounts as standing seven feet tall.

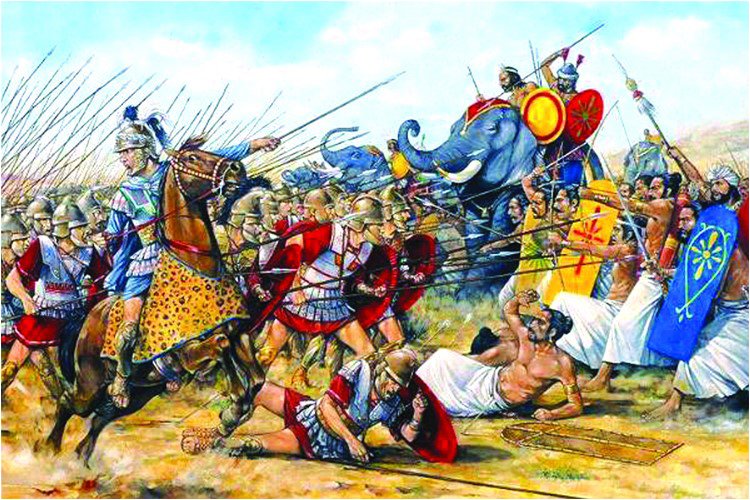

In May 326 BCE, the European and Paurava armies faced each other across the banks of the Jhelum. By all accounts it was an awe-inspiring spectacle. The 34,000 Macedonian infantry and 7000 Greek cavalry were bolstered by the Indian king Ambhi, who was Porus’s rival. Ambhi was the ruler of the neighbouring kingdom of Taxila and had offered to help Alexander on condition he would be given Porus’s kingdom.

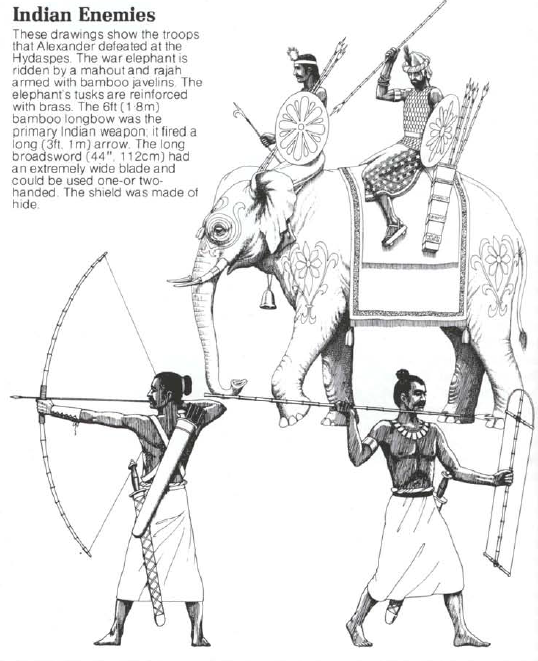

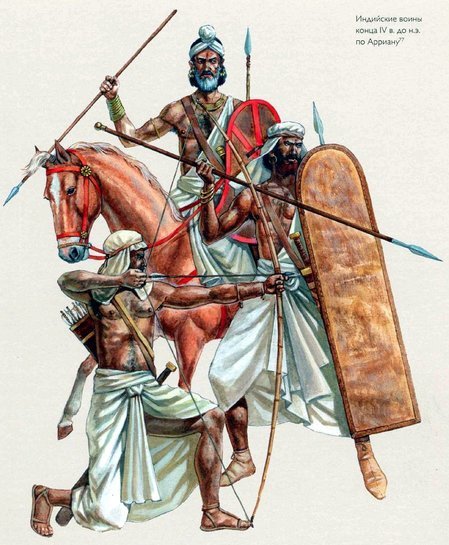

Facing this tumultuous force led by the genius of Alexander was the Paurava army of 20,000 infantry, 2000 cavalry and 200 war elephants. Being a comparatively small kingdom by Indian standards, Paurava couldn’t have maintained such a large standing army, so it’s likely many of its defenders were hastily armed civilians. Also, the Greeks habitually exaggerated enemy strength.

According to Greek sources, for several days the armies eyeballed each other across the river. The Greek-Macedonian force after having lost several thousand soldiers fighting the Indian mountain cities, were terrified at the prospect of fighting the fierce Paurava army. They had heard about the havoc Indian war elephants created among enemy ranks. The modern equivalent of battle tanks, the elephants also scared the wits out of the horses in the Greek cavalry.

Another terrible weapon in the Indians’ armoury was the two-meter bow. As tall as a man it could launch massive arrows able to transfix more than one enemy soldier.

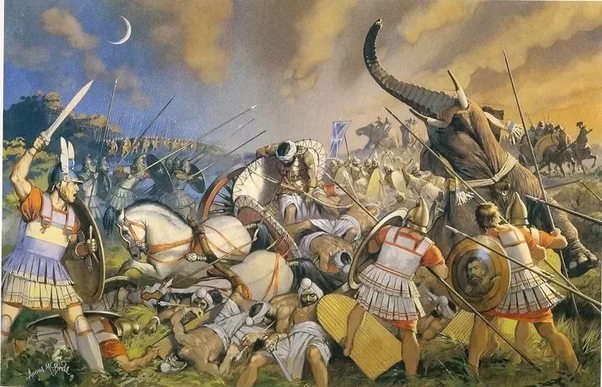

Indians Strike

The battle was savagely fought. As the volleys of heavy arrows from the long Indian bows scythed into the enemy’s formations, the first wave of war elephants waded into the Macedonian phalanx that was bristling with 17-feet long sarissas. Some of the animals got impaled in the process. Then a second wave of these mighty beasts rushed into the gap created by the first. The elephants either trampled the Macedonian soldiers or grabbed them by their trunks and presented them up for the mounted Indian soldiers to spear them to their deaths. It was a nightmarish scenario for the invaders. As the terrified Macedonians pushed back, the Indian infantry charged into the gap.

In the first charge, by the Indians, Porus’s son wounded both Alexander and his favourite horse Bucephalus, the latter fatally, forcing Alexander to dismount.(6) This was a big deal. In battles outside India the elite Macedonian bodyguards had provided an iron shield around their king, yet at Hydaspes the Indian troops not only broke into Alexander’s inner cordon, they also killed Nicaea, one of his leading commanders.

According to the Roman historian Marcus Justinus, Porus challenged Alexander, who charged him on horseback. In the ensuing duel, Alexander fell off his horse and was at the mercy of the Indian king’s spear. But Porus dithered for a second and Alexander’s bodyguards rushed in to save their king.

Plutarch, the Greek historian and biographer, says there seems to have been nothing wrong with Indian morale. Despite initial setbacks, when their vaunted chariots got stuck in the mud, Porus’s army “rallied and kept resisting the Macedonians with unsurpassable bravery”.(7)

Macedonians: Shaken, Not Stirred

The Greeks claim Porus’s army was eventually surrounded and defeated by Alexander’s superior battle tactics, but there are too many holes in that theory. It is acknowledged by Greek and Roman sources that the fierce and constant resistance put up by the Indian soldiers and ordinary people everywhere had shaken Alexander’s army to the core. They refused to move further east. Nothing Alexander could say or do would spur his men to continue eastward. The army was close to mutiny. These are not the signs of a victorious army, but a defeated group of soldiers would certainly behave in this manner.

Says Plutarch: “The combat with Porus took the edge off the Macedonians’ courage, and stayed their further progress into India. For having found it hard enough to defeat an enemy who brought but 20,000 foot and 2000 horse into the field, they thought they had reason to oppose Alexander’s design of leading them on to pass the Ganges, on the further side of which was covered with multitudes of enemies.”

The Greek historian says after the battle with the Pauravas, the badly bruised and rattled Macedonians panicked when they received information further from Punjab lay places “where the inhabitants were skilled in agriculture, where there were elephants in yet greater abundance and men were superior in stature and courage”.

Indeed, on the other side of the Ganges was the mighty kingdom of Magadh, ruled by the wily Nandas, who commanded one of the most powerful and largest standing armies in the world. According to Plutarch, the courage of the Macedonians evaporated when they came to know the Nandas “were awaiting them with 200,000 infantry, 80,000 cavalry, 8000 war chariots and 6000 fighting elephants”. Undoubtedly, Alexander’s army would have walked into a slaughterhouse.

Hundreds of kilometres from the Indian heartland, Alexander ordered a retreat to great jubilation among his soldiers.

Partisans Counterattack

The celebrations were premature. On its way south towards the sea, Alexander’s army was constantly harried by Indian partisans, republics and kingdoms.

In a campaign at Sangla in Punjab, the Indian attack was so ferocious it completely destroyed the Greek cavalry, forcing Alexander to attack on foot.

In the next battle, against the Malavs of Multan, he was felled by an Indian warrior whose arrow pierced the Macedonian’s breastplate and ribs.

The Battle of Hydaspes was Alexander’s last major open-field battle. Everything else was a skirmish compared with it. The Macedonians and Greeks were not the same tough guys anymore. Always on the retreat, constantly harried by Indian soldiers during Alexandrian army’s retreat through hostile kingdoms, they trekked south towards the sea, hoping to escape this nightmare. If ever there was a defeated army, this one certainly behaved like one.

Says Military History magazine: “Although there was more fighting, Alexander’s wound put an end to any more personal exploits. Lung tissue never fully recovers, and the thick scarring in its place made every breath cut like a knife.”

Alexander never recovered and died in Babylon (modern Iraq) at the age of 33.

Zhukov’s Take

“Following Alexander’s failure to gain a position in India and the defeat of his successor Seleucus Nikator, relationships between the Indians and the Greeks and the Romans later, was mainly through trade and diplomacy. Also the Greeks and other ancient peoples did not see themselves as in any way superior, only different.”

The above statement by Russia’s legendary general on the Macedonian invasion of India in 326 BCE is significant because unlike the prejudiced colonial and Western historians, the Greeks and later Romans viewed Indians differently.

According to Arrian, “Moreover, they discovered that they were tall in stature, in fact as tall as any men throughout Asia, most of them being five cubits in height, or a little less. They were blacker than the rest of men, except the Ethiopians; and in war they were far the bravest of all the races inhabiting Asia at that time.”

In fact, Arrian and other Greeks say the Indians were relentless in their attacks on the invaders. They say if the people of Punjab and Sindh were fierce, then in the eastern part of India “the men were superior in stature and courage”.

All this is glossed over by Western historians, in whose view the one claimed victory over the small Paurava kingdom of Porus amounts to the “conquest of India”. But the Greeks made no such claim.

Battle of Hydaspes – Hardest Ever

Greek contemporary writers describe the Battle of Hydaspes (Jhelum) in June 326 BCE as the hardest fought of all Alexander’s battles. Frank Lee Holt, a professor of ancient history at the University of Houston, writes(8): “The only reference in Arrian’s history to a victory celebration by Alexander’s army was after the battle with Porus.”

Alexander’s army did not indulge in celebrations after the Battle of Gaugamela where they defeated a gigantic Persian army of 200,000 men. No wild festivities were announced after the Battle of Issus where they defeated a mixed force of Persian cavalry and Greek mercenaries.

The fact they celebrated after the Battle of Hydaspes suggests they considered themselves extremely lucky to survive after the clash with the Hindu army, with its feared elephant corps.

If Porus Lost, Why Reward Him?

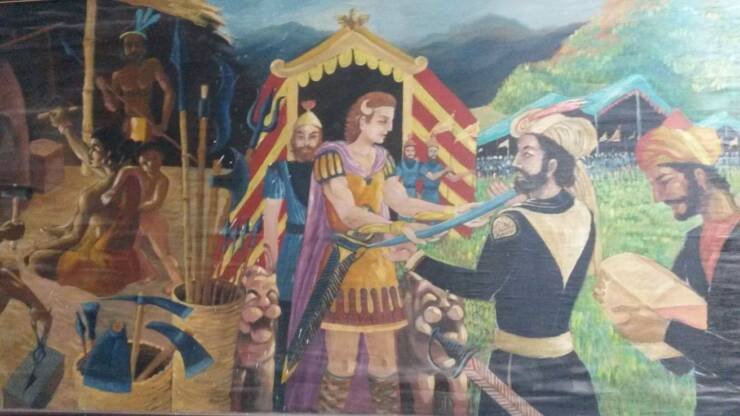

One of the iconic exchanges in world history is that between the ‘two kings. When Alexander met Porus after the battle, he is reported to have asked him how he wanted to be treated. Porus replied: “Like a king.” If there was anything else he wanted for himself, Alexander said, he only had to ask. “Everything is included in that,” Porus said.

This is certainly not an exchange between a victorious ruler and a defeated one, but it has all the appearance of a negotiation. According to Arrian, “When they met, Alexander reined in his horse and looked at his adversary with admiration. He was a magnificent figure of a man, over seven feet high and of great personal beauty; his bearing had lost none of its pride; his air was of one brave man meeting another, of a king in the presence of a king with whom he had fought honourably for his kingdom.”

According to the Greeks, Alexander was apparently so impressed by Porus he gave back his kingdom plus the territories of king Ambhi of Taxila who had fought alongside the Macedonians. This is counterintuitive. Ambhi had become Alexander’s ally on the condition he would be given Porus’ kingdom. So why reward the enemy, whose army had just mauled the Macedonians?

The only possible answer is at the Battle of Hydaspes the Macedonians realised they were dealing with an enemy of uncommon valour. The mauling Alexander’s troops received was a greater order of magnitude than ever before. Military historian Nigel Cawthorne(9)) says the Macedonian army suffered 4,000 casualties. That’s a staggering number considering Paurava was a tiny kingdom.

A more probable scenario is that sensing defeat the Macedonians called for a truce, which Porus accepted. This is in line with the behaviour of Hindu kings throughout history – from Prithviraj Chauhan at the First Battle of Tarain in 1191 to the numerous wars fought against the British, and to the 1948, 1965 and 1971 wars in the modern era, Hindus have shown an unbroken – and unnecessary – merciful streak. Instead of chasing the defeated army and finishing him off, they have allowed the foreign invader to live and fight another day.

At Hydaspes, the Indian king may have offered them a deal that was difficult to turn down. In return for his enemy Ambhi’s territories – which would secure the Paurava kingdom’s frontiers – Porus would assist the Macedonians in leaving India safely.

Alexander’s post-Hydaspes charitable behaviour, as described in Greek accounts, is uncharacteristic and unlikely. For, in several battles before and after Hydaspes, he had massacred or enslaved everyone in the cities he subdued.

Why Pay Off a Vassal?

Before the battle, Alexander gave king Ambhi 1000 talents (25,000 kilos) of gold for fighting alongside the Macedonians. The only explanation is Ambhi too was driving a hard bargain. He knew the rattled Macedonian army was seeking to quickly exit India. Ambhi thought he could use the Macedonians to remove his rival Porus. However, Porus’ decision to offer Alexander combat checkmated those plans.

The reason for placating Ambhi with gifts was that the moment he stepped into India, Alexander had met fierce resistance. Comparatively small Hindu kingdoms had checked his advance at great cost to life and military assets. Unlike the Persian king who had fled from the battlefield, the rulers of small Indian republics such as the Aspasians, Assakenoi, Bazira and Ora (located in or around the Swat Valley in modern Pakistan) had led from the front while defending their citadels. They nobly played their role as guardians of India’s gateway.

At Massaga, for instance, 7,000 male and female Indian mercenaries decided to fight Alexander rather than switch allegiance and fight their hosts. They put up a fierce fight, meeting a glorious death “which they would have disdained to exchange for a life with dishonour”.(10)

Tired of Fighting: Lamest Excuse in History

Greek sources say Alexander retreated from India because his soldiers were weary, homesick and close to mutiny. This is a line happily latched on to by Western historians as it gives them the almost perfect alibi to bail out Alexander. But that’s not how professional armies work. Imagine if German soldiers had told Hitler they were tired of fighting? They would have been summarily shot. In Alexander’s time, the punishment was crucifixion.

The Macedonian army had a system of rotation whereby large batches of veteran soldiers were released to return home (with sufficient gold and slaves). In their place, fresh troops eagerly poured in from Europe.

Greek historian Diodorus Siculus(11) notes that after the battle with the Paurava army, Alexander received a reinforcement from Greece at the river of more than 30,000 infantry and nearly 6,000 cavalry; also suits of armour for 25,000 infantry, and 100 talents of medical drugs.

Mutiny and Inglorious Retreat

The Battle of Hydaspes had drained Macedonian morale; after the next battle, with the republic of the Kathas at Sangla, which left thousands of Macedonians killed and wounded, the army was on the point of rebellion. The tipping point came when Pheges, an Indian king who decided not to fight but let Alexander pass through his territory, confirmed the massive size and ferociousness of the Nanda army east of the Ganges.

Facing a mutiny, Alexander saved his face by offering a sacrifice to the gods as a preliminary to crossing the Indus. As expected the omens were unfavourable and Alexander ordered a retreat. “The army received the announcement with tears of joy and grateful shouts,” writes historian, numismatist and archaeologist Awadh Kishore Narain. “They hardly realised what was still in store for them. For Alexander had yet to fight some of his fiercest and most dangerous battles.”(12)

In January 325 BCE, Alexander learnt that the Oxydracae (Shudrakas) and the Malli (Malavs), who lived around modern Multan, were mobilising to block his path to the sea. Note that these two kingdoms could have chosen to let the Macedonian army pass through their territories; the foreign soldiers would have looted some crops and cattle and the Indian republics could not have had to endure sieges and loss of life. But instead the Shudrakas and Malavs mobilised an army of 100,000 men and 900 war chariots.

Faced with the prospect of fighting once more, Alexander’s men were soon on the point of rebellion. Alexander had to lie to them that the people ahead were not warlike and the ocean was close (it was almost 700 km further south) so the troops would agree to fight.

The plight of the Macedonian army has an uncanny resemblance to the travails faced by two large and defeated armies of the past – Napoleon’s Grande Armee and the German Wehrmacht. Both armies were harried by Russian partisans all the way from Moscow to the border of Russia. It is always the defeated army that is harried, not a winning one.

Indeed, if they were weary of constant warring, it is inexplicable why these soldiers chose to fight their way through obstinately hostile Indian territories. The homesick soldiers would have preferred the garrisoned northwestern route they took while coming in. Why would a brilliant commander subject himself and his troops to further violence when all they wanted was a peaceful passage home?

Clearly, Alexander and the Macedonians were in a mess and not thinking straight. Not the sign of a victorious army.

Indian Resistance

In order to understand the scale and intensity of the resistance the Macedonians faced in India, one only has to look at Alexander’s march from Kabul to the Beas to the lower Indus. Narain writes: “Alexander took almost two years to cover this area, which is proportionately a longer time for a lesser space than in his other campaigns, and the battles fought were as dangerous, as glorious, as full of bravery and adventure.”

A vivid example of the Macedonian army coming unstuck was during the battle against the Malavs. Cawthorne writes: “Alexander called for scaling ladders, but his men refused to climb them. So he climbed up alone, holding a light shield over his head. At the top he killed the defenders who barred his way, then stood alone on top of the battlements – the perfect target for any archer.”

The Macedonians still refused to follow their king, and in fact begged him to come down. Alexander was so frustrated that he jumped down inside the citadel. It was only at this point that the Macedonians gathered their wits and courage and decided to save their king. Alexander was joined by Leonnatus and Abreas, a highly decorated guards officer. The Macedonians rallied and stormed the gate but were greeted by a volley of arrows. Abreas fell, shot in the face, and Alexander was struck by an arrow that pierced his breastplate and lodged in his chest.

The enraged Macedonians killed all the men, women and children in the fort. “This campaign of brutality now became part of Alexander’s strategy. The violent resistance slowed down the army’s progress and it took Alexander five months to reach the sea. During this period he fought a series of bloody battles in a war largely inspired by Brahmin priests. He hanged any Brahmin that fell into his hands, reserving crucifixion for civil leaders that opposed him. He asked one Brahmin why he had encouraged his king to revolt. His reply was: ‘Because I wished him to live with honour or die with honour.’ This bloodthirsty repression simply stored up resentment for the future. By 300 BCE, every Macedonian garrison in Punjab had been slaughtered.”(13)

Death in the Desert

After reaching the mouth of the Indus river, Alexander divided his army into two. One part was to leave by ships that would hug the Makran coast and sail to Babylon (modern Iraq). The second army led by Alexander would march on foot (as his cavalry had been entirely destroyed by Indians at Sangla) through Balochistan into Persia and enter Babylon.

Alexander’s march through modern Balochistan, during which he lost the majority of his troops, as well as the accompanying women and children, shows he was willing to take a punt on the merciless desert rather than face the Indians in the northwest all over again. Undoubtedly, the Aspasians, Assakenoi, Massagans and others, whose homelands he had devastated, would have challenged his weary army on the narrow mountain passes.

Alexander’s march through modern Balochistan, during which he lost the majority of his troops, as well as the accompanying women and children, shows he was willing to take a punt on the merciless desert rather than face the Indians in the northwest all over again. Undoubtedly, the Aspasians, Assakenoi, Massagans and others, whose homelands he had devastated, would have challenged his weary army on the narrow mountain passes.

Nineteenth century philologist John McCrindle’s account offers ample light on the humiliations faced by Alexander’s men, suggesting they were a demoralised army. “Most of Alexander’s historians admit that all the hardships which his army suffered in Asia are not to be compared with the miseries which it here experienced,” he writes.(14)

Owing to the great length of the march, the soldiers suffered greatly, tortured alike by raging heat and unquenchable thirst. When their provisions ran short the soldiers came together and killed most of the horses and mules. They ate the flesh of these animals, which they professed had died of thirst and perished from the heat. No one cared to look very narrowly into the exact nature of what was going on, both because of the prevailing distress and also because all were alike implicated in the same offence.

Alexander himself was not unaware of what was going on, but he saw that the remedy for the existing state of things was to pretend ignorance of it rather than permit it as a matter that lay within his cognisance.

What followed was one of the saddest episodes of the Macedonian campaign. With the horses and mules being eaten, it was no longer easy to convey the soldiers labouring under sickness, nor others who had fallen behind on the march from exhaustion, nor the women and children in the baggage train. Thousands were left behind on the road from sickness, others from fatigue or the effects of the heat or intolerable thirst, while there were none who could take them forward or remain to tend them in their sickness. “The majority perished in the sand like shipwrecked men at sea,” writes McCrindle.

Need for Glory

David J. Lonsdale, a lecturer in Strategic Studies at the University of Hull, writes: “Alexander’s invasion of India and Napoleon’s invasion of Russia in 1812 both appear reckless and unnecessary from a strategic perspective. Therefore, perhaps they can both be explained by the sheer naked ambition of the two commanders.”(15)

Alexander’s tragedy was that he was in a Catch-22 situation. The Macedonians and Greeks welcomed the wealth from the conquered lands, but the man who ensured this flow was virtually persona non grata back home.

In Greek eyes a Macedonian was a barbarian. Much as he wished to be treated as a demigod, the Greeks didn’t acknowledge as having any Hellenic heritage. In fact, they hated Alexander for sacking their cities and enslaving the people of the Greek cities. In his own country, he was an outsider for being half-Albanian, from his mother’s side. Some even suspected him of murdering his own father.

So in order to retain the loyalty of his troops, Alexander had to wage constant war while also taking great personal risks in battle. For, he could not be seen as weak, let alone beaten.

Creating myths and resorting to falsehoods were integral to Alexander’s strategy. A few years before the Indian campaign, a part of the Macedonian army was massacred by the Scythians at Polytimetus, present day Tajikistan. In order to avoid loss of morale, Alexander warned his surviving troops not to discuss the massacre with other soldiers who were to follow him into India.

The mythmaking around the Alexander cult had reached such ridiculous proportions that Strabo the Greek historian wrote: “Generally speaking, the men who have written on the affairs of India were a set of liars…Of this we became the more convinced whilst writing the history of Alexander.”

Conclusion

The contemporary Indian observations made by the kings and priests are at once philosophical and patriotic. According to Narain, “They indicate two things. First, there was an emotional love of freedom and a patriotic sense of honour. Secondly, India, with her peculiarly philosophical attitude, was not at all overawed by the greatness of Alexander and not only regarded the Indian campaign as most unjustifiable but also anticipated its futility.”(16)

Both Chanakya and the youthful Chandragupta Maurya, who seem to have had a firsthand view of Alexander’s campaign in Punjab, understood the Indian pulse of reaction correctly. Narain concludes: “Even while Alexander was in Gedrosia (Balochistan), the only alien satrap appointed by him in India was murdered and when Alexander was dying in Babylon, Chandragupta Maurya and Chanakya, perhaps with the help of Porus, were liberating and unifying Punjab as a prelude to the final overthrow of the great Nanda power of the Ganges valley, which the army of Alexander had feared so much that the latter was forced to withdraw from the Beas. Alexander’s campaign in India was therefore certainly not a political success. And it is also true that it left no permanent mark on its literature, life or government of the people. The name of Alexander is not found in Indian literature. Certainly, Alexander did not intend his conquests in India to be as meaningless as this. But it was so.”

SOURCES

- Quintus Curtius, ‘History of the Wars of Alexander’, (Book XIII, 17)

- ‘Greek Alexander Romance’, https://www.britannica.com/art/Alexander-romance

- N.S. Rajaram, ‘Porus’s Defeat of Alexander at the Battle of Hydaspes’, https://voiceofindia.me/2016/10/05/porus-defeat-of-alexander-at-the-battle-of-hydaspes-jhelum-n-s-rajaram/

- Arrian the Nicomedian, ‘The Anabasis of Alexander’ (Book IV, 25), https://archive.org/stream/cu31924026460752/cu31924026460752_djvu.txt

- Rama Shankar Tripathi, ‘History of Ancient India’, p 118

- Arrian (Book 15, 14, 4)

- Plutarch, ‘The Life of Alexander’, http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Plutarch/Lives/Alexander*/8.html

- Frank Lee Holt, ‘Alexander the Great and the Mystery of the Elephant Medallions’

- Nigel Cawthorne, ‘Alexander the Great’ p. 115

- R.C. Majumdar, ‘Classical Accounts of India’

- Diodorus Siculus, ‘Bibliotheca Historica’, XVII. 95

- A.K. Narain, ‘Greece & Rome’, Vol. 12, No. 2, Alexander the Great, pp. 155-165

- Nigel Cawthorne, ‘Alexander the Great’ p. 115

- ‘John Watson McCrindle, ‘The Invasion of India by Alexander the Great as described by Arrian, Q. Curtius, Diodoros, Plutarch and Justin’, https://archive.org/stream/cu31924028252546/cu31924028252546_djvu.txt

- David J. Lonsdale, ‘Alexander the Great: Lessons in Strategy’

- A.K. Narain, ‘Greece & Rome’, Vol. 12, No. 2, Alexander the Great, p. 162

–The writer is a globally cited defence analyst. His work has been published by leading think tanks, and quoted extensively in books on diplomacy, counter terrorism, warfare and economic development. The views expressed are personal and do not necessarily reflect the views of Raksha Anirveda

–The writer is a globally cited defence analyst. His work has been published by leading think tanks, and quoted extensively in books on diplomacy, counter terrorism, warfare and economic development. The views expressed are of the writer and do not necessarily reflect the views of Raksha Anirveda