The latest demand by POTUS to reoccupy Bagram Air Base in Afghanistan, shows his modus operandi, insisting on a new toy after every few days, to further his MAGA ambition. The writer analyses the reasons why the regional countries are against this latest demand from the maverick POTUS.

The renewed debate on a possible US return to Bagram Air Base — once the most fortified American installation in Afghanistan — has sparked concerns across Eurasia. Among the most significant of these is China’s apprehension that an American re-establishment at Bagram could serve dual purposes: counter-terrorism and strategic surveillance of China’s western nuclear and missile infrastructure.

While Washington officially frames its interest in Bagram as part of its “over-the-horizon” counterterrorism capabilities against Islamic State–Khorasan (IS-K), Beijing interprets it through the lens of great-power rivalry — as a forward intelligence and potential strike platform targeting China’s sensitive western region.

A possible US return to Bagram Air Base — once the most fortified American installation in Afghanistan — has sparked concerns across Eurasia. Among the most significant of these is China’s apprehension that an American re-establishment at Bagram could serve dual purposes: counter-terrorism and strategic surveillance of China’s western nuclear and missile infrastructure

Why Bagram Matters

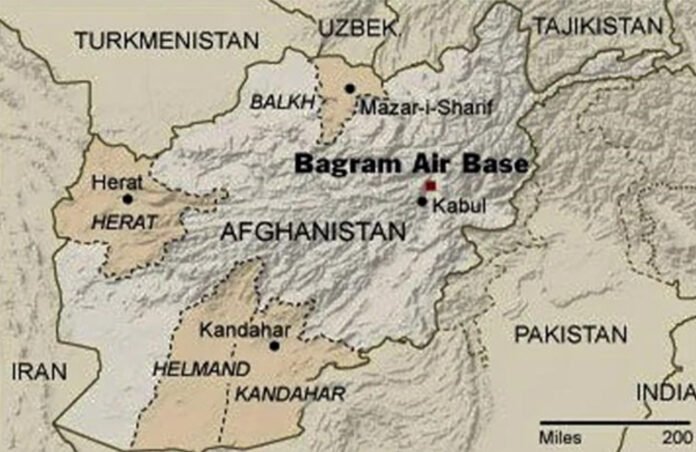

Bagram Air Base is located roughly 50 km north of Kabul, in Parwan Province. Its geographic significance stems from its central position in the Hindu Kush, offering aerial access to the entire Central Asian arc.

Key distances (approximate straight-line):

- Bagram to Urumqi (Xinjiang capital) — 1,000 km

- Bagram to Kashgar (PLA missile and nuclear logistics hub) — 750 km

- Bagram to Lop Nur nuclear testing site — 1,400 km

- Bagram to Khunjerab Pass (China–Pakistan border) — 500 kms

Thus, any high-altitude ISR (Intelligence, Surveillance, Reconnaissance) assets based in Bagram — especially drones, satellites uplink nodes, or signals intelligence platforms — could monitor and map China’s entire western missile complex.

China’s Nuclear and Missile Infrastructure in Xinjiang

China’s nuclear architecture has historically centred in its western interior, far from coastal vulnerabilities. Key sites include:

Lop Nur: Nuclear testing range and research hub, now home to advanced missile telemetry and re-entry observation systems.

Washington officially frames its interest in Bagram as part of its “over-the-horizon” counterterrorism capabilities against Islamic State–Khorasan (IS-K), Beijing interprets it through the lens of great-power rivalry — as a forward intelligence and potential strike platform targeting China’s sensitive western region

Korla and Delingha: Ballistic missile testing bases for DF-21, DF-26, and DF-31 series.

Kashgar–Hotan region: Logistics corridor linking the People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force (PLARF) to western deployments.

Karamay–Urumqi: Strategic communications and nuclear command redundancies.

From a US perspective, these regions represent the “blind spot” of Western Pacific intelligence coverage — too deep inland for surveillance from Guam or the South China Sea, yet vital for understanding China’s second-strike survivability and missile dispersal doctrine.

Bagram’s elevation (1,490 meters) and proximity make it an ideal vantage point to overcome this intelligence gap.

Bagram: A Potential Strategic Platform

During the US occupation (2001–2021), Bagram evolved from a Soviet-era airstrip into a joint operations and surveillance hub. It hosted:

- Long-range RQ-4 Global Hawk drone flights.

- SIGINT/ELINT units tracking regional communications.

- A secure data fusion centre linked to CENTCOM networks.

- Hardened runways capable of supporting B-52s and C-17s.

Should the US regain access, even temporarily, the base could again support ISR platforms, UAVs, and high-altitude reconnaissance over western China, Pakistan, Iran, and Central Asia.

Thus, for Beijing, the threat is not direct nuclear targeting, but rather deep surveillance and strategic mapping — which can neutralise the opacity of China’s deterrence posture.

Any high-altitude ISR (Intelligence, Surveillance, Reconnaissance) assets based in Bagram — especially drones, satellites uplink nodes, or signals intelligence platforms — could monitor and map China’s entire western missile complex

US Strategic Logic behind Interest in Bagram

Intelligence Triangulation: The United States faces increasing difficulty monitoring China’s western military build-up. Bagram could form a triangulated ISR axis:

- Guam – Pacific approach.

- Diego Garcia – Indian Ocean flank.

- Bagram – Continental rear surveillance.

Together, these enable full-spectrum coverage of China’s nuclear infrastructure and logistics corridors, including the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) passage through Xinjiang.

Missile Early Warning and Counterforce Data. Modern nuclear deterrence relies on targeting data fidelity. Having real-time electromagnetic, radar, and satellite relay from within 1,000 km of China’s missile fields would vastly improve US targeting accuracy in a hypothetical counterforce scenario.

Containment of Eurasian Rivals. Bagram’s location offers observation of:

- China’s Western Command,

- Iran’s missile complexes, and

- Russia’s southern flank (Tajik and Kyrgyz territories).

Hence, a US return could serve as a tri-vector containment node under the broader Indo-Pacific and Eurasian competition.

Why China Views This as a Strategic Threat

China’s reaction to any US return to Bagram would be swift and hostile, for several intertwined reasons:

Surveillance of Nuclear Command and Control: Bagram’s electronic reach can cover the PLA Rocket Force’s command relays, and intercept telemetry during missile testing or redeployment in Xinjiang.

For Beijing, the threat is not direct nuclear targeting, but rather deep surveillance and strategic mapping — which can neutralise the opacity of China’s deterrence posture

Undermining of Strategic Ambiguity: China’s deterrence relies partly on opacity — uncertainty over the size, location, and mobility of its nuclear arsenal. Persistent US ISR coverage from Bagram could unravel this ambiguity, diminishing deterrence stability.

Encirclement Anxiety: From Beijing’s perspective, a US base in Afghanistan completes the encirclement triangle: US presence in the East (Japan, Guam), in the South (Diego Garcia), and now in the West (Bagram). Such a posture would be interpreted as a strategic net around China, not merely counterterrorism.

Domestic Symbolism and Xinjiang Sensitivity: Any American presence near China’s Xinjiang region — especially one linked to intelligence collection — is politically toxic for Beijing, given its sensitivity about ethnic unrest and international scrutiny of Xinjiang policies

Afghanistan’s Refusal: The Regional Layer

Afghanistan’s current rulers (the Taliban) have categorically rejected US proposals to regain Bagram on account of various pragmatic reasons, namely;

Sovereignty – The Taliban views any US base as a violation of the Doha Agreement and a return to the US occupation. Regional Alignment- Afghanistan today leans diplomatically towards China, Russia, Iran, and Pakistan, all of whom oppose a US footprint. Economic Leverage – The Taliban expect investment through the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) extension, which would be jeopardised by an American base. Security Concerns- Any US base would be an immediate magnet for insurgent attacks, including from ISIS-K. Thus, Kabul’s denial is not merely ideological, but strategically aligned with China’s and Russia’s security calculus.

For Afghanistan maintaining neutrality safeguards both Chinese and Russian investment and avoids making Afghanistan a battlefield once again

India’s Position: Strategic Caution

India’s stance is nuanced. New Delhi, despite historical cooperation with the US, publicly supports Afghan sovereignty and regional consensus against foreign bases. A renewed US presence would provoke Chinese and Pakistani reactions, complicating India’s balancing strategy. It could reignite militant flows into Kashmir. India prefers stability through diplomacy and economic engagement, not re-militarisation. India also recognises that US presence in Bagram, while offering intelligence on China, would increase Sino-Pak collusion — a net strategic loss. Hence, India tacitly supports Afghanistan’s refusal, even while quietly benefitting from the containment it indirectly provides.

Pakistan’s Position: Double-Edged Calculus

Pakistan, despite decades of cooperation with US intelligence, has opposed a renewed American base near its border.

Reasons include: Domestic backlash — cooperation with the US would invite Taliban and extremist retaliation. Chinese partnership — Pakistan’s CPEC and broader economic survival depends on Beijing’s goodwill.

Strategic leverage — Islamabad benefits more from mediating between Washington and Kabul than hosting an American base. Thus, Pakistan’s alignment with Afghanistan’s denial is pragmatic self-preservation.

Military Feasibility: What the US Could Do from Bagram

Should the US somehow regain access, Bagram could host RQ-4B Global Hawk, MQ-9 Reaper, or next-gen stealth drones for long-endurance ISR. Operate signal relay nodes for Low Earth Orbit (LEO) satellite constellations. Support electronic intelligence aircraft (RC-135 variants) on rotational basis. Function as a data fusion hub linking CENTCOM, Indo-Pacific Command, and the NSA’s Eurasian collection grid collectively, these would transform Afghanistan into an intelligence wedge between China’s western flank and Pakistan’s CPEC corridor.

Strategic Implications for the Region

For Afghanistan: Maintaining neutrality safeguards both Chinese and Russian investment and avoids making Afghanistan a battlefield once again.

For China: Keeping the US out of Bagram preserves the secrecy of its nuclear deterrent and secures its Belt and Road arteries.

For the US: Losing access to Bagram weakens its “over-the-horizon” capabilities in continental Eurasia — a major intelligence setback.

For India: The denial prevents an escalation spiral but also limits India’s intelligence reach into China’s west, which New Delhi can compensate for via satellite assets.

For India the denial to US prevents an escalation spiral but also limits India’s intelligence reach into China’s west, which New Delhi can compensate for via satellite assets

For Pakistan: It avoids another cycle of proxy war and retains room to balance between Washington and Beijing. Overall, the denial reinforces Eurasian multipolarity — symbolically showing that no single power, not even the US, can reimpose unilateral regional dominance.

The Bagram Equation and the Nuclear Shadow

Overall, the US presence in Bagram, if re-established, would not directly threaten Chinese nuclear assets through attack, but it would deeply threaten China’s strategic opacity — its shield of invisibility.

Bagram’s geolocation, high-altitude environment, and infrastructure make it an unparalleled intelligence outpost for real-time monitoring of China’s nuclear and missile programmes in Xinjiang.

For Pakistan it helps to avoid another cycle of proxy war and retains room to balance between Washington and Beijing. Overall, the denial reinforces Eurasian multipolarity — symbolically showing that no single power, not even the US, can reimpose unilateral regional dominance

That potential alone is sufficient for Beijing to mobilise diplomatic, economic, and possibly security mechanisms to keep Bagram out of US hands. Afghanistan’s refusal, supported by India and Pakistan for their own strategic reasons, thus serves a larger Eurasian consensus: preventing the re-militarisation of the heartland and keeping the balance of power continental, not trans-oceanic.

In essence, Bagram today is less a military base than a geopolitical symbol — of who controls the flow of intelligence in the heart of Asia.

China sees its return to US control as a breach of the emerging Eurasian compact. India and Pakistan, for all their rivalries, both see prudence in keeping Afghanistan sovereign. And Afghanistan itself, long a pawn, now finds leverage in saying NO.

-The author retired as Major General, Army Ordnance Corps, Central Command, after 37 years of service. A management doctorate and expert on defence modernisation, he is the author of four books, including the Amazon bestseller “Breaking the Chinese Myth,” and a frequent media commentator. He is affiliated with several leading defence and strategic studies institutions in New Delhi. The views expressed are of the writer and do not necessarily reflect the views of Raksha Anirveda