“After the rapid transformations and the excitement of the past few years, the US-India bilateral relationship must now settle down: leaders should focus on strengthening ties by embracing small, concrete opportunities to cooperate rather than target a high-profile initiative, as the relationship needs time and substance to mature.”

-From a report titled “India In the Indian Ocean Region; Re-calibrating US Expectations” – American Security Project, US

1971: At the height of the India-Pakistan War the US sends in its nuclear armed Seventh Fleet menacingly towards Kolkata, while a British fleet steams in with Mumbai as its target. President Richard Nixon phones Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, saying he wants to “piss on the Indians”; the latter agrees Indians are “such bastards”. The intervention of the Russian Pacific Fleet, which sails in from Vladivostok, prevents a joint US-British assault on India.

1974: In response to India’s atomic bomb test, the US forms the Nuclear Suppliers Group – which includes every Western country – to block India’s access to nuclear technology and fuel. No such cartel was created in response to China’s nuclear test in 1964.

1992: Under pressure from the US, Russian president Boris Yeltsin cancels a major deal between Glavkosmos and the Indian Space Research Organisation to develop an Indian cryogenic engine (required for manned space missions) thereby delaying India’s deep space programme by decades.

2012: Following the IAF’s rejection of US jets in the IAF’s $10 billion Medium Multirole Combat Aircraft competition, US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton orders the CIA to open India’s Khalistan file, with a view to restart the terrorist movement in Punjab.

2013: Devyani Khobragade, India’s deputy consul general in New York, is arrested, handcuffed, and put through strip and cavity searches, procedures normally used for criminals. (She wasn’t the first; in June 2003, former defence minister George Fernandes was strip-searched in Washington.)

2014: The United States Commission on International Religious Freedom – the nodal government body for “religious freedom in the world” equates the Islamic terrorist group ISIS with the RSS: “Hindu Nationalist Group Seeking to Cleanse Christian Presence From #India Is Not Unlike ISIS.”

2022: The US State Department claims attacks on members of minority communities, including killings, assaults and intimidation are happening throughout India. These include cow vigilantism – assaults on non-Hindus for allegedly slaughtering cows or trading in beef.

2023: Eric Garcetti, the ambassador designate to India, tells a US Congressional committee that he would actively interfere in India’s internal affairs by supporting groups that are inimical to India.

You get the picture – these are not the acts of a friendly country. The history of India-US relations is littered with many such rocky episodes that would have irreparably damaged relations but for the fact that Indians have short memories and an incurably forgiving nature.

In fact, India-US ties got off to a rocky start in the early years of the Cold War. First up, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru failed to develop a rapport with the Americans. Former US diplomat Dennis Kux writes about Nehru in India and the United States: Estranged Democracies: “The Indian leader had a considerable bias that seemed to combine the anti-American social prejudices of the British elite and the anti-American policy views of the left-wing of the British Labour Party.”

In 1949 when Nehru visited the US, one particular incident reinforced his belief that the Americans were crass and uncouth. Robert Beisner writes in Dean Acheson: A Life in the Cold War that “a US White House secretary pointed towards Nehru’s daughter Indira Gandhi, and spoke about ‘these foreigners who come over here and take our money away from us’.”

India was also put off by the importance given in the US to racists such as Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, who advocated the creation of a purer white race through genetic research.

In 1950, annoyed by the warm welcome given in the US to Pakistani Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan, Nehru wrote to his sister Vijaylakshmi Pandit, the Indian ambassador in Washington: “The Americans are either very naive or singularly lacking in intelligence. They go through the same routine whether it is Nehru or Liaquat Ali. It does appear that there is a concerted attempt to build up Pakistan and build down, if I may say, India. It surprises me how immature in their political thinking the Americans are! In their dealings with Asia they show a lack of understanding which is surprising.”

India’s primary aim should be to absorb the world’s best technologies. In this it should emulate China, which has become an economic superpower after 40 years of technology transfers along with big-ticket investments from US multinationals

At the same time, the Americans thought Nehru was too full of himself. Secretary of State Dean Acheson wrote: “I was convinced that Nehru and I were not destined to have a pleasant personal relationship. He was so important to India’s survival and India’s survival so important to all of us that if he did not exist – as Voltaire said of God – he would have to be invented. Nevertheless, he was one of the most difficult men I have ever had to deal with.”

To be fair to the Americans, Nehru made a strategic blunder by spurning the US offer to give China’s permanent seat in the UN Security Council – and the veto power – to India. Since he was beginning to tilt towards socialism and refused to join the anti-Soviet bloc, the Americans decided to strike a Faustian bargain with suicidal Pakistani generals rather than deal with a lotus eating, day dreaming idealist.

The big thaw

Since the early 1990s when India opened up to the world, starry-eyed Washington think tanks have hyped up India’s potential as a force multiplier on the US chessboard. Mostly they prescribe a transactional relationship where the US will help India grow into a global power on the condition that New Delhi assists the US to manage China’s rise. This is exactly what the warlords in Washington have offered the likes of Ukraine, Poland and the Baltic countries for needling Russia.

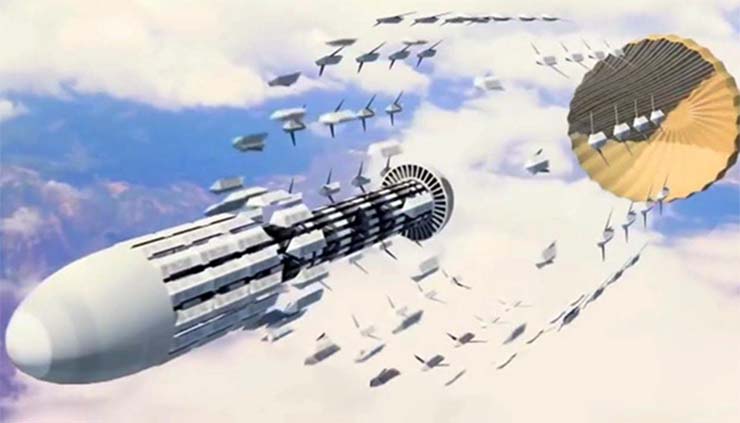

There are two problems with this approach. One, most Indians are too proud to compromise their autonomy and become America’s sidekick. Secondly, since 2012 when India’s Agni-V nuclear-tipped ballistic missile covered every inch of Chinese territory in its range, the Chinese have got a reality check. Since then, with India deploying sea-launched ballistic missiles and heavily-armed mountain divisions, Beijing today has very limited room to manoeuvre against India. So New Delhi doesn’t need the US to ‘manage’ China.

In this backdrop there should be no earthshaking expectations from Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s planned US visit later in 2023. Like before, there will be Congressional speeches, White House dinners and diaspora meetings. But after the song and dance routine is over, it’s going to be business as usual. And that’s exactly what India should focus on – business and technology. The US is a leader in many areas and is a vast storehouse of technology – especially futuristic. For instance, while India has no semiconductor industry worth the name, the US is on the verge of quantum computers.

India’s primary aim should be to absorb the world’s best technologies. In this it should emulate China, which has become an economic superpower after 40 years of technology transfers along with big-ticket investments from US multinationals. Today, there is hardly an American company that doesn’t have a manufacturing base in China.

America’s primary interest in training with India’s armed forces seems to be to find out how its hardware stacks up against the latest Russian-built weapons. India knows this; when the Indian Air Force trains with the US Air Force and Royal Air Force, its Sukhoi-30MKI pilots are under orders not to use the aircraft’s radar, so as to prevent the Americans and British from estimating its range and spectrum of capabilities.

Technology transfer is the key. The US is a relatively declining power and will be keen to have a large country like India on its side. What India should insist on is for the US to give us the crown jewels of its industry, especially electronics, defence and space technologies. A lot is already happening. For instance, the Moon Mineralogy Mapper on board India’s successful Chandrayaan-I moon probe – which discovered water on the lunar surface – came from NASA.

With tech samurai Japan offering aviation joint ventures and high-speed trains, the US can be persuaded to part with its top secrets. The inflow of bleeding-edge technology can propel India to the big league – economically and militarily.

If there’s any doubt how the US can swing things India’s way, just look at the India-US nuclear deal. The deal not only enabled Russia to offer reactors and Kazakhstan and Australia to offer uranium, it also sent the Nuclear Suppliers Group hurtling towards irrelevance.

Double edged sword

They say America’s friendship and enmity are both dangerous. Defence deals and geopolitical ties with the US come with their flip side due to the nature of these engagements. For India’s armed forces, joint exercises are an opportunity to train with the technologically advanced American armed forces, but such exercises can sometimes backfire.

America’s primary interest in training with India’s armed forces seems to be to find out how its hardware stacks up against the latest Russian-built weapons. India knows this; when the Indian Air Force trains with the US Air Force and Royal Air Force, its Sukhoi-30MKI pilots are under orders not to use the aircraft’s radar, so as to prevent the Americans and British from estimating its range and spectrum of capabilities.

If the Americans are prepared to grow out of their Cold War mindset and admit that Pakistan – and its 100-odd nukes – are a threat to peace, then India and the US can tango

Indian military officers who come in contact with US defence personnel may even be compromised by American intelligence agencies. In fact, Indian counterintelligence agents, sent to study courses in the US as part of the so-called War on Terror, were considered compromised as at least one of them – Rabindra Singh of RAW – became a double agent and was exfiltrated out of India by the CIA.

US whistleblower Edward Snowden revealed that American spying on India – including the ruling BJP – is on the upswing. Following his tip that the NSA conducts a bigger espionage programme against India than on Russia or China, Indian embassy employees in Washington started using manual typewriters instead of computers to compose classified messages.

Defanging the jehadi snake

It is now well-known that Pakistan was created by the retreating British with America’s blessings. From a useful Cold War stooge, Pakistan has now transmogrified into a country where the arrow of time is travelling backwards, taking it into a spiral of medieval madness. As the country teeters towards dysfunctional status, there is a possibility that its Islamic Bomb could end up in the hands of ISIS or some other terrorist group.

If the US is sincere about having a strategic partnership – forget the illusion of friendship – with India, then it has to help New Delhi dismantle Pakistan into several harmless constituents that can never again become a threat to India. Only if Pakistan is broken up into at least five separate entities – Sindh, Balochistan, Saraiki Punjab, Punjab and Pashtunistan (which may merge with Afghanistan) – will we finally see peace on our western borders. If the Americans are prepared to grow out of their Cold War mindset and admit that Pakistan – and its 100-odd nukes – are a threat to peace, then India and the US can tango.

Two countries – worlds apart

Other than democracy, India and the US have little in common. India is a largely liberal and pluralistic society whereas the US is a strongly Puritanical nation where 60 per cent of the population believes in Creationism, accepts the Bible as literal truth and believes the Biblical nonsense that Earth was created in seven days. While the liberals in the Democratic Party are traditionally against a powerful, independent India, we must also be on guard against the agenda of the Republican right wing which is allied with fundamentalist Christian forces.

After the rapid transformations and the excitement of the past few years, the US-India bilateral relationship must now settle down: leaders should focus on strengthening ties by embracing small, concrete opportunities to cooperate rather than target a high-profile initiative, as the relationship needs time and substance to mature.”

For, the Christian Right in the US sees India as the last major stronghold of the pagans that Christ’s stormtroopers need to kick down. Any steps taken by the Indian government to stop their aggressive proselytization efforts is enough for them to go back to their media and play victim. And as day follows night, the likes of the Washington Post and the New York Times will play up the lie that Hindus are an intolerant people who persecute Christians and Muslims.

There are numerous lobbies in the US opposed to India for ideological, religious or geopolitical (or a blend of all three) reasons. As the Khobragade episode made it amply clear, the American attitude towards India hasn’t changed since the Cold War. Despite the plentiful trade that is happening in both directions, the two countries are still not sure what kind of relationship they want.

In this backdrop, the US think tank, American Security Project, offers a neat solution. In a report titled India In the Indian Ocean Region; Re-calibrating U.S. Expectations, it says: “After the rapid transformations and the excitement of the past few years, the US-India bilateral relationship must now settle down: leaders should focus on strengthening ties by embracing small, concrete opportunities to cooperate rather than target a high-profile initiative, as the relationship needs time and substance to mature.”

– The writer is a globally cited defence analyst. His work has been published by leading think tanks, and quoted extensively in books on diplomacy, counter terrorism, warfare and economic development. The views expressed are of the writer and do not necessarily reflect the views of Raksha Anirveda