On October 2, 2025, at a military base in Bhuj, Gujarat, during the Vijayadashami/Shastra Puja ceremonies, Defence Minister Rajnath Singh issued a stern warning to Pakistan regarding its activities in the Sir Creek area. He declared that any misadventure by Pakistan in the Sir Creek sector would be met with a decisive response — one strong enough to “change both history and geography.” He referenced Operation Sindoor, claiming that during that operation, Pakistani attempts to penetrate Indian defences from Leh to Sir Creek were foiled, and Indian forces exposed Pakistan’s vulnerabilities.

The Genesis of the Dispute

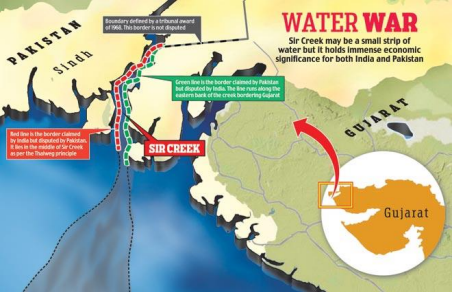

Sir Creek is a 96 km strip of water in the marshes of the Rann of Kutch in Gujarat. It is a disputed region between India and Pakistan. The creek roughly separates the Kutch region in India and Pakistan’s Sindh province. Sir Creek opens up into the Arabian Sea. It was originally named Ban Ganga and was renamed Sir Creek during colonial times after a British official. Sir Creek is a strategically important region, and Indian and Pakistani troops had clashed in the Rann of Kutch in the 1965 war. It is an important fishing ground and is one of the largest fishing sources in Asia. Another reason for its significance is the possible presence of oil and gas reserves under the sea in that area. It is currently unexplored because of the ongoing border dispute. The area is also of great ecological importance, as it is home to flamingos and other migratory birds in the winter.

Today, the dispute is that India claims half of Sir Creek and, therefore, the marshlands that border Pakistan’s Keti Bunder Wildlife Sanctuary, while Pakistan cites one of those colonial-era deals and insists the boundary lies east of the creek, giving it access to the heartland of Gujarat. Islamabad relies on the 1914 Bombay Government resolution’s map and textual articulation, which places the boundary on the eastern flank of the creek.

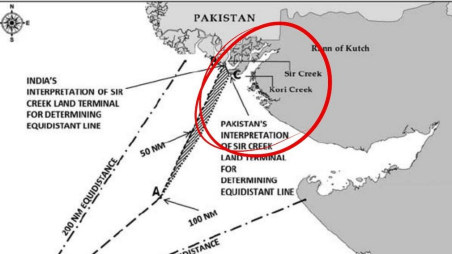

The 1968 Indo-Pak Arbitral Tribunal (on the larger Rann of Kutch boundary) resolved much of the western land boundary but explicitly left Sir Creek out of final settlement, noting its uncertain and changeable character and the difficulty of applying a fixed line in a shifting tidal plain. The Tribunal recommended that the boundary be described in functional terms (e.g., the ‘centre of the navigable channel’) but did not fix an unambiguous, mutually accepted coordinate line — leaving open interpretation over maps and implementation. That omission has been consequential: since the territorial baseline onshore remains contested, the maritime line beyond becomes contested as well. New Delhi argues for the thalweg (mid-channel) principle, widely used in international river boundary law — especially where navigation or shifting channels make a bank-based line impractical. A mid-channel boundary supports Indian claims to a larger maritime sector seaward.

The Geographic, Strategic and Economic Context

Sir Creek holds strategic, economic, and ecological significance. The creek lies near the Rann of Kutch, an area where India and Pakistan clashed during the 1965 war. Control over this region influences maritime security and surveillance.

At first glance, Sir Creek is marginal: mudflats, mangroves, no cities. But the location matters for three reasons:

Economic (EEZ and resources): Where the land boundary ends determines the direction of the maritime boundary; a small shift at the creek can yield hundreds of square kilometres of EEZ and access to offshore hydrocarbon prospects. The marshlands of Sir Creek are believed to contain significant oil and gas reserves. International law is unforgiving here: coastal turning points determine vast maritime entitlements.

Fisheries and Human Security: Thousands of small fishers from both countries ply these waters. Without a clear, mutually accepted line, arrests and unpleasant incidents occur frequently, producing local humanitarian tensions and intermittent diplomatic rows.

Strategic/Operational Considerations: The creek abuts the approaches to the Indus delta and, more broadly, the Arabian Sea. Control of local channels influences patrolling patterns, surveillance access and the ability to interdict or protect littoral traffic — especially in a high-tension environment. Recent events demonstrate the military sensitivity of this apparently marginal geography. It also presents India with a direct route to the Karachi Port. The nearest major Pakistani airbase to Sir Creek is

PAF Base Masroor in Karachi. While not immediately adjacent to the estuary, it is the most strategically significant airbase in the region and plays a key role in defending Pakistan’s southern coastal area. The Indian Air Force Station in Naliya, Gujarat, is the airbase in closest proximity to the Sir Creek region, lying about 90 km away. Naliya AFS is a crucial installation for defending India’s western border and has seen recent upgrades, including the deployment of the indigenous HAL Tejas aircraft.

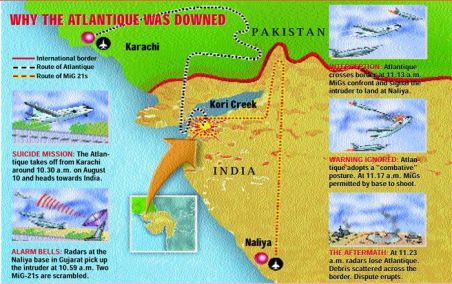

The Atlantique Incident

As reported in India today on August 10, 1999, in the Rann of Kutch in Gujarat, two MiG-21s took off from the Naliya air base at 11 a.m. to investigate an ‘unidentified’ aircraft entering the Indian airspace in the Rann of Kutch region. Though normally airspace violations are routine, however, this time the game turned deadly. Two Indian MiGs scrambled fast enough to confront the intruder – a Pakistani Atlantique reconnaissance aircraft. When the MiGs (one behind and one to its side) tried to force the Atlantique to land at Naliya, the plane instead veered sharply to the left towards the border.

When Sqn Leader PK Bundela relayed this ‘posture’ to his air base, his radio crackled seconds later with an order to shoot. Bundela fired a single heat-seeking air-to-air Matra missile that hit the Atlantique on the port

side, causing it to burst into flames and hurtle down into the Kori Creek wasteland. The two MiGs returned to the air base to a hero’s welcome. As Bundela put it modestly: “It was just my day.” This is how vulnerable this area can get. In case an incident like this happens now, a war with Pakistan would certainly be guaranteed.

Recent Pakistan Designs

In the last couple of years (and with reported intensification in 2025), media and defence-analysis outlets have reported that Pakistan has been quietly strengthening infrastructure — tracks, observation posts, and limited permanent positions — on its side of the Sir Creek marshes and adjacent areas. At the same time, there have been reports that Pakistan objects to Indian infrastructure projects in the border area, successfully pressing for a temporary halt to some Indian civilian works. Indian authorities and analysts describe these moves as a deliberate attempt by Islamabad to create facts on the ground (or marsh) and to assert control over approaches and access. It is believed that Pakistan has recently replaced its Rangers with regular Army troops of approximately six battalions’ strength.

India’s political leadership has publicly flagged concern. In October 2025, India’s Defence Minister warned Pakistan against ‘misadventure’ in Sir Creek and characterised the Pakistani activity as a military build-up; he stressed that India would respond decisively to any aggression in the area. Such statements indicate New Delhi views these developments not merely as local infrastructure competition but as actions with wider security implications.

Decoding Pakistan’s Intent

At the outset, it would be safe to assume that if Pakistan strengthens its administration and physical presence in the disputed marshes, it will increase its bargaining power in any future delimitation talks. Pakistan’s moves can be framed as an asymmetric response to Indian civil-security or infrastructure projects nearby. Denying India freedom of action or pressuring New Delhi to stop certain works is a non-kinetic means of asserting claims. Demonstrating capacity to operate in a marshy littoral environment signals to New Delhi and external observers that Pakistan retains options in the western littoral theatre. Given the narrowness of approaches from Sir Creek to parts of the Indus delta and beyond, such signalling has military resonance.

It has also been observed that Pakistan, along with Chinese technological collaboration, is establishing advanced airborne surveillance systems and radars in this area to monitor India’s maritime activities as well as influence the projected India-Middle East Economic Corridor.

It is also believed that replacing para-military forces with regular troops has a great tactical significance as it lends support to locating terrorist launch pads in the region to support infiltration of terrorist groups, as well as smuggling of arms, ammunition and impetus to the influx of drugs. India has raised concerns that the poorly monitored, unfenced marshlands could be used by terrorists to infiltrate its territory. The perpetrators of the 2008 Mumbai attacks are believed to have used this route.

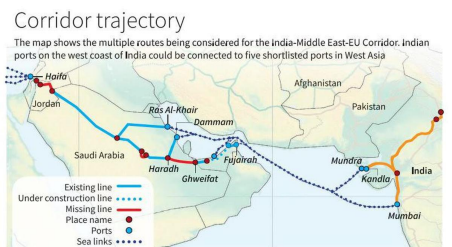

Threat to India-Middle East Economic Corridor

Pakistan’s military escalation in the Sir Creek region, along with the unresolved maritime dispute, could indirectly threaten the security of the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC). Any conflict in this area has the potential to destabilise the Arabian Sea, an essential maritime gateway for the IMEC’s ‘Eastern Corridor’. While not a direct component of the IMEC, the security of the Arabian Sea is critical for the corridor’s Eastern Segment, which links India’s west coast ports (like Mundra) with the Gulf region. Increased Pakistani naval activity and the disputed maritime boundary raise the risk of maritime incidents or miscalculation, which could lead to disruptions for shipping traffic across the broader sea. China would like to influence this outcome as IMEC is seen as a rival to its Belt and Road Initiative.

India’s Response

Any realistic pathway requires parallel confidence-building: local fisher-level arrangements, joint coast-guard communications, and clear rules on construction and patrols. In the present context, in line with India’s declaration of putting the Indus-Water Treaty into abeyance as well as a post-Operation Sindoor scenario with provocative statements by senior leaders from both sides, a dialogue between the two nations seems impossible.

It would also be pertinent to note that Sir Creek’s geomorphology is sensitive to sea-level rise, sediment transport, and changing river discharge. Climate change will alter channels, create new mudflats and could submerge historical reference points — complicating the legal stability of any boundary tied to physical features. That makes a legally and technically flexible solution (e.g., treaty language that foresees shifting channels and includes mechanisms for joint technical updates) far more durable than a rigid coordinate line based on ephemeral features.

Conclusion

Sir Creek is a classic example of how a small, shifting piece of geography can carry outsized strategic, economic and political weight. The dispute is not merely legalistic: it touches livelihoods, resource access and the signalling calculus between two nuclear neighbours. Pakistan’s recent infrastructure and posture adjustments have raised tensions and prompted a robust Indian public warning. These developments underline that the dispute is not dormant.

A resolution is technically straightforward compared with other India-Pakistan problems — it only requires political will and technical trust. Pragmatic steps (joint surveys, temporary buffer arrangements, and climate-resilient treaty language) can prevent small incidents from becoming major crises. Given the mutual benefits of delimitation (resource clarity, reduced fisher arrests, predictable law enforcement), both sides have an interest in converting technical pathways into a political settlement — but that will require restraint on incremental “facts on the ground” and a commitment to engage in good faith.

-The author retired as Major General, Army Ordnance Corps, Central Command, after 37 years of service. A management doctorate and expert on defence modernisation, he is the author of four books, including the Amazon bestseller “Breaking the Chinese Myth,” and a frequent media commentator. He is affiliated with several leading defence and strategic studies institutions in New Delhi. The views expressed are of the writer and do not necessarily reflect the views of Raksha Anirveda