Introduction: The emerging frontier for potential combat between nations is seemingly the oceanic floor. Powerful nations are scrambling for dominance in this field. Essentially, the term “Seabed Warfare” refers to operations incorporating the sea floor, targeting cables (data and power), sensors and energy transmission, and extraction infrastructure. Seabed warfare is defined as “operations to, from and across the ocean floor.” In general, the target of this warfare is the infrastructure in place on the seabed such as power & telecom cables, deployed weapon systems and natural resources extraction systems. Many major naval powers have already shaped their ideas, formulated approaches and implemented their seabed warfare strategy in their national interest. India has a 7517 km long coastline and numerous valuable assets on the sea floor. How India views this emerging conflict domain and shapes its seabed warfare strategy is going to be vital for our future energy security and economic growth.

Background

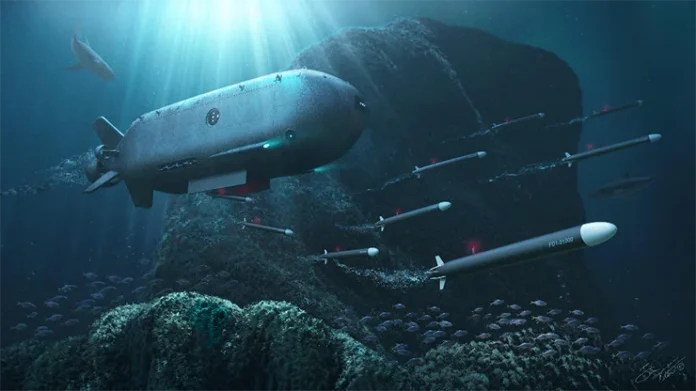

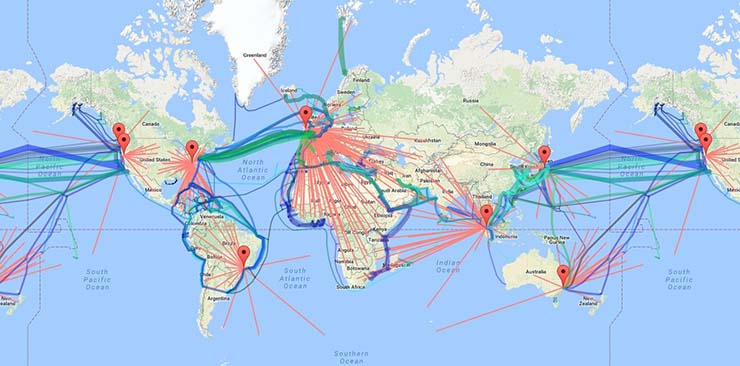

Seabed warfare began unknowingly in the 1960s with the United States Navy’s Operation Ivy Bells, a cooperative effort by the USN, CIA, and NSA to wiretap Soviet undersea communication cables amid heightened tensions between the USA and the USSR during the Cold War and extract useful information for national gains. In the decades since then, the advent of modern technologies has increased manifolds, the densities of undersea pipelines, optical fibres and power cables, which traverse the oceans between nations and continents alike, allowing data transfer in telecommunication and for the distribution of oil and gas. Huge importance is being accorded to the protection of these assets by user nations and for them, it means strengthening their undersea surveillance, detection and warfare capabilities by investing in expensive and capable scientific technologies, deep-diving spy submersibles, and/or submarines with the special abilities to deploy mini-subs and drones using underwater cameras and hi-tech sonars. A few powerful navies such as the USA, the UK, France, Russia and China have already announced their seabed strategies.

Challenges Posed by the Deep Sea & Seabed

The deep sea is often referred to as the part beyond the continental shelf. The average depth of oceans is about 4000m, and with few exceptions, current commercial systems predominantly operate up to 3000m. The deep sea poses numerous challenges such as:

- No sunlight and total darkness. Hence it is very tough to explore the seabed.

- High pressures and associated risks of material failure of operating vehicles. The environment offers distinctive challenges for the AUV and ROV design, construction equipment and systems.

- Extremely cold temperatures, unpredictable, unknown and challenging terrain, with transforming nature of the seabed.

- Seabed deeper than 2000 metres necessitates special acoustics and salinity considerations for communications and application sonar.

- The depth of operations also imposes limitations on vessel design and its power requirements. Syntactic foam (mostly used in tethers) becomes heavier with increasing depth, thus demanding more power to operate effectively, thus requiring a heavier system. The power that an ROV draws on often comes from a tether to a surface vessel, presenting challenges to the descending ROV as the cable becomes more lossy with the greater length.

- Higher sea states and poor visibility adversely affect the operations of tethered or untethered ROVs.

- Underwater currents or drift of water in the sea or near the seabed can hinder the activity of the AUVs and ROVs (with or without tether).

- Many seabed areas are volcanic with exploding geysers, chemicals and seabed materials posing risks to operations.

Initiatives by Major Powers

More recently, a considerable surge of interest has been witnessed in activities focused on the exploitation of seabed resources for economic gains, as well as the vulnerabilities resulting from growing reliance by states on seabed infrastructure and notably undersea cables estimated to carry 95% of all international digital data.

United States: The USA has been involved in applications of seabed warfare since the 60s Cold War itself. More lately, there have been growing concerns about the safety and vulnerabilities of its seabed assets. Consequently, internal deliberations and debates on the issue have led to the conclusion that for the US Navy, it means building the most expensive spy submarine ever, a $ 5.1 billion high-tech spy submarine filled with robots and divers that would patrol the deepest reaches of the ocean and deploy mini-subs and drones that can battle hostile forces while withstanding the crushing pressure of the deep is aimed at protecting American commercial and security interests below the seas. With wars in the Middle East and Europe and numerous conflicts going on in various regions around the world, and as the sole superpower, the USA is focusing intensely on augmenting its assets to safeguard against seabed warfare.

United Kingdom: The UK has also understood the importance of seabed security and voiced its concerns about Russia’s seabed activities, especially after the damage to Nord Stream gas pipelines. In 2021, the UK announced the development of a new Multi-Role Ocean Surveillance Ship (MROS) to safeguard national seabed/undersea infrastructure and the first of its class is already operating its AUVs/ROVs. Conceptual changes are being envisaged to follow on MROS. The UK has established a strategic partnership with Norway to “counter shared threats in the undersea domain” including threats to undersea infrastructure. RN has already ordered a crewless submarine in Dec 2022 and is developing AUVs to detect underwater mines with France.

France is leading discussions on the issues involved, including the challenges these developments pose to international maritime law, and the difficulties in both detecting and attributing malign activity in this domain. With a significant economic stake in possessing the world’s second-largest Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). More than 50 of the world’s main submarine cables currently in operation – over 10% of the global total – run to France and its overseas territories. France has promulgated its seabed warfare document, which suggests that the seabed should be considered a new domain, similar to cyber and outer space. The strategy outlines how to safeguard the French forces’ ability to secure their freedom of action in an increasingly contested environment, watch over the country’s underwater infrastructure and key resources, as well as defend the country’s undersea military and industrial interests. Its key aspects focus on improving the country’s knowledge of the seabed, better monitoring of the underwater domain and securing its ability to act under the surface by augmenting resources. France has established specific departments and appointments in the Navy headed by a two-star Admiral to handle this emerging domain swiftly. France aims to develop at least one ROV and one autonomous uninhabited vehicle able to operate down to 6,000 m by 2025. Others include new-generation hydrographic vessels with supporting remote offboard systems and mine-warfare capabilities with new systems incorporating AUV/ROV platforms.

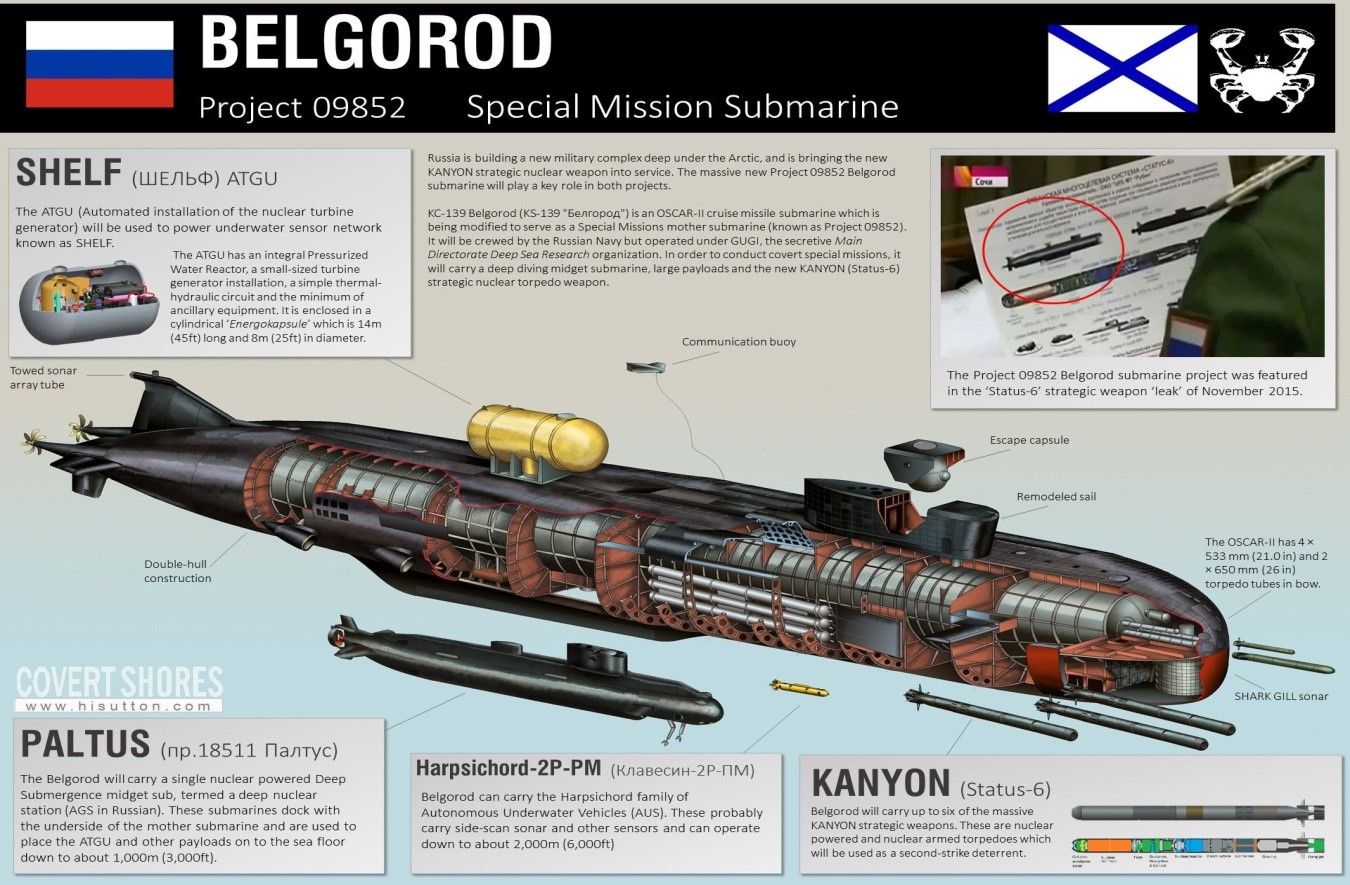

Russia is the only country with a fleet of special mission subs for seabed warfare and espionage and is expanding its capability further. Russia’s fleet includes two massive submarine motherships that each carry one or two deep-diving submersibles. These can be employed for covert seabed missions, including wreck plundering. The largest of these is BS-64, a stretched DELTA-IV-class submarine, which is being augmented by an even larger mothership Belgorod (bigger and heavier than Delta and second only to the 30,000-ton Typhoon class). These submarines are operated for the Main Directorate of Deep Sea Research and work on undersea communications and sensor networks, hydrocarbon exploitation, submarine rescue and investigating wreckage.

In addition to the submarines, specially-equipped surface vessels (popularly dubbed as spy ships) and equipped with a hangar for extremely deep-diving crewed submersibles and multiple ROVs are also operated by Russia. These ships have been found near international undersea cables, downed aircraft of major navies, shipwrecks and important undersea pipelines. In general, Russian assets are capable of being utilised in the placement of acoustic sensors, surveying wreckage at the sea floor to glean intelligence, and tapping undersea cables etc. It holds many highly capable underwater assets and technologically advanced systems, drones and remote vehicles to undertake sub-sea operations. The Ukraine war has also demonstrated numerous seabed warfare tactics adopted by the Russians for strategic advantages. In the Baltic Sea in 2015, Russia interfered with the completion of the SweLit underground power cable and more recently the Nord pipelines. The Russian government accords high priority to seabed warfare as is evident from the secretive expansion of its fleet assets in this domain.

China considers Seabed warfare as a new kind of hybrid armed conflict that targets ocean-floor infrastructure like under-sea power and telecommunication cables, as well as natural resource extraction & transportation systems. It is emerging as an important component of Chinese operations to win future wars. China’s deep-sea policy is enunciated by the communist regime’s Five-Year Plan (2016-2020) for scientific innovation, which considers deep-sea technology to be a strategic high technology that serves national security. Building a real-time ocean surveillance system has become a national project of the highest importance in Beijing’s national planning documents. Consequently, China is developing highly capable undersea drones & underwater vehicles and modernising its undersea fleet to exploit seabed warfare opportunities. China has already launched the world’s first artificial intelligence-operated drone carrier, an unmanned maritime mothership that can be used for maritime research, intelligence-gathering and even potentially repelling enemy drone swarms. The autonomous ship, known as Zhu Hai Yun has a top speed of 18 knots. Its AI operating system allows it to carry 50 flying, surface and submersible drones that can launch and recover autonomously. China wishes to deploy this ship to carry out marine scientific research and observation, marine disaster prevention and mitigation, environmental monitoring and offshore wind farm maintenance etc. The drones can also be utilised for data/information collection and disruptions.

Implications and Options for India

Warring armed forces in Europe have recently resorted to targeting energy pipelines, seabed cables (data and power), sensors and energy transmission linkages and oceanic resource extraction infrastructures etc.

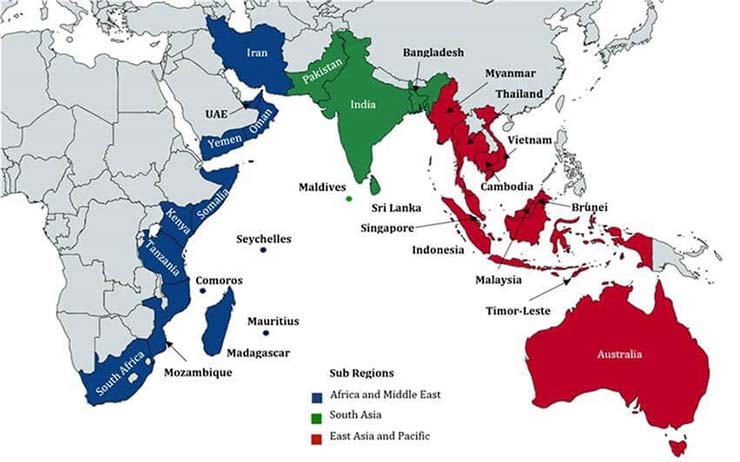

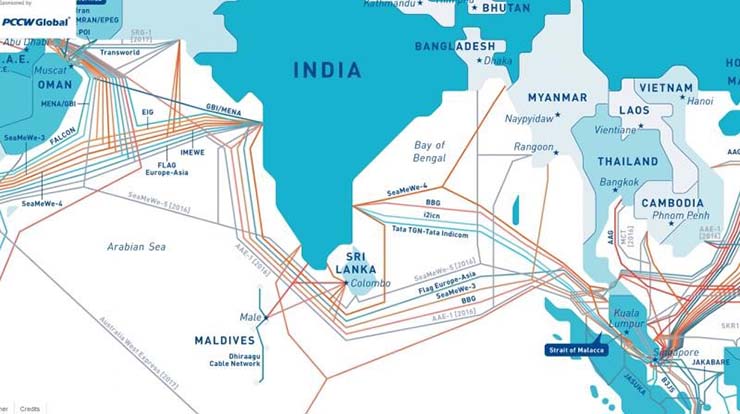

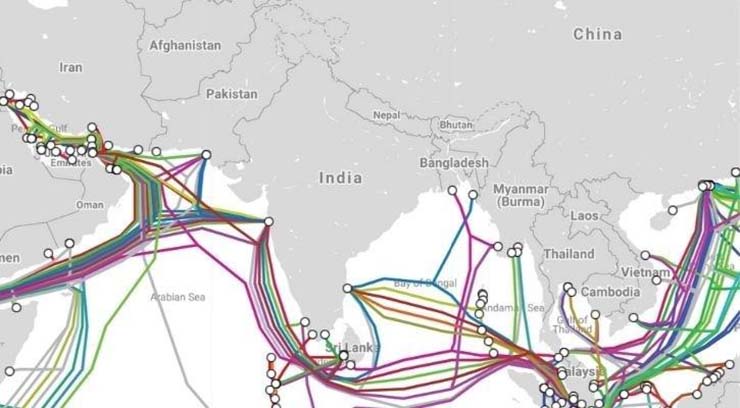

The Indian Ocean is a conduit for submarine cables that both connect IOR nations and send data further afield. But just as shipping is concentrated at oceanic choke points such as the Malacca Strait and Bab el-Mandeb Strait, so too are submarine cables, making them vulnerable to attack at these locations. Subsea oil and natural gas pipelines are of immense importance in the Indian Ocean, connecting major fields including Mumbai High, Neelam and Heera Ratna basin. Iran is currently considering extending its subsea natural gas pipeline from Oman to India, which would connect to Porbandar in Gujarat. The 5Bn United Arab Emirates-India gas pipeline (proposed in May 2023) would also connect to Gujarat. Disruptions in these pipelines and to the data cables, conduits and fibre optic cables in IOR would adversely disrupt trade apart from causing financial crisis in India and IOR nations.

It is only correct to expect that the warring states or the inimical actors would, sooner or later bring the seabed warfare to the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) since this region is a hub of the world’s largest energy trade, communications, internet and business applications.

India holds a key position and strategic location in the IOR and being the most credible naval power in the region, it is expected to tackle seabed vulnerabilities and attacks for its national and regional interests. With the changing nature of traditional and asymmetric warfare, a long coastline, vast EEZ, and valuable assets in its coastal zones and high seas, it is imperative that India evaluates the looming seabed warfare threats appropriately and prepares itself adequately to meet them in the future.

The following are recommended to effectively handle the nuances of seabed warfare:

- The Government of India (GoI) should create a new hierarchical structure or chain of command in its Ministry.

- Ministry of Shipping, Indian Navy (IN), Indian Coast Guard (INCG), Intelligence Bureau (IB) and other maritime, private players & miscellaneous organisations can create their requisite channels and appointments under the guidance and monitoring of MoD.

- Information exchange Synergy can be created between multiple government agencies and private players involved at all levels utilising various information-sharing

- India’s Strategic “Doctrine on Seabed Warfare” be formulated and promulgated to all the agencies concerned.

- India should accelerate the augmentation of highly advanced and superior undersea technologies, and assets (ROVs/AUVs/DSRVs/armed/unarmed autonomous drones and intelligence/information gathering and monitoring systems & sensors) to safeguard our assets from such warfare.

- India should take the lead in IOR and develop partnerships with like-minded nations to brainstorm and create a robust and reliable strategic response to seabed warfare.

Conclusion

The Ukraine war alone has amply demonstrated that seabed infrastructure is a legitimate war-time target for state and non-state actors alike. While this warfare is not a new phenomenon however, the scale of new seabed infrastructure, and modern civilisation’s unparalleled reliance on commerce, trade, energy and communication networks, means the threat is real & emergent and the consequences of asset disruption or destruction are very severe. The seabed domain deserves focused renewed attention by the Indian government, military organisations, maritime sector & intelligence agencies and subsequent incorporation into our national defence strategies. India needs to watch seabed warfare developments in Europe and other regions closely as an indication of potential proliferation in the IOR. The Indian government needs to publish its Seabed Warfare Doctrine or a strategy document and create necessary command and control systems in the country to handle seabed warfare in the future. As a regional power, India must take the lead and coordinate with the IOR States to secure the Indian Ocean seabed critical infrastructure. While it is understood that seabed warfare is extremely difficult to defend against, and presently no nation is adequately equipped or prepared to fully defend its seabed. However, India must make a beginning and take it forward expeditiously.

-The writer is a former Indian Navy Submarine Officer. Commissioned in 1991 (10+2 X First Course), he is an alumnus of Naval Academy, Goa and DSCSC Mirpur, Dhaka, Bangladesh. He served on Kilo Class Submarines, Commanded INS Sindhurakshak and is a specialist in Anti-Submarine Warfare and a deep sea diver. He has been Directing Staff of the prestigious DSSC, Wellington, Tamil Nadu and instructor at the Submarine Training Centre, INS Satavahana, Visakhapatnam. The views expressed in the paper are personal. He can be reached at sumit12in@gmail.com.

–The writer is a former Indian Navy Submarine Officer. He is an underwater weapons and missile specialist and a deep sea diver. An alumni of DSCSC Mirpur, Dhaka, he has been Directing Staff of the prestigious DSSC, Wellington, Tamil Nadu and instructor at the Submarine Training Centre, INS Satavahana, Visakhapatnam. He regularly writes on military strategy, warfare and technologies. He is an active member of the Strategic Think Tank USI, STRIVE and the Chakra dialogues foundation. The views expressed in the paper are personal. He can be reached at sumit12in@gmail.com