The relations between India and the Maldives date back centuries, with the first settlers in the Maldives arriving from India and present-day Sri Lanka around the 5th century BC. In addition, there were deep trade links. In contemporary times, it is India, Maldives’s nearest neighbour, which has aided the latter in every crisis, be it the military response against the attempted coup (1988; Operation Cactus), or as a first responder to the 2004 tsunami or the 2014 water scarcity (Operation Neer), or the supply of anti-COVID medicines (Operation Sanjeevani). Indian teachers and doctors have, and continue to play a significant role in the health and education sectors of the Maldives. India also supplies most of the essential items (vegetables, food items, construction materials, etc) at special rates. Several large infrastructure projects are being developed by India, while Indian tourists contribute to its economy. In addition, India provides defence and security assistance in the form of joint defence and security exercises, training of personnel of the Maldivian National Defence Force as well as its police, etc.

The foundation of the Maldives-PRC relations was laid by former president Maumoon Abdul Gayoom (1978-2008) – he was the first Maldivian President to visit the PRC in 1984 and then again in 2006. However, on account of his pro-Indian policy, Chinese influence had remained limited in the Maldives, with the PRC investing about US$ 46 million in infrastructure. Nasheed’s campaign in 2008 criticized Gayoom for cozying up to the PRC. On being elected as president in 2008, Nasheed emphasized an “India First” policy ostensibly because he looked at India as a role model for the Maldives’ nascent democracy and had a better understanding of the Maldives’ reliance on India for economy, security and development, as well as its ties with the USA. After Nasheed (MDP) resigned in 2012, Mohammed Waheed (2012-2013) visited the PRC, emphasized an increase in trade and tourism, and sought a US$ 500 million loan for housing projects. PRC’s position in the Maldives improved substantially after Abdulla Yameen (PPM) won the 2013 presidential elections. PRC’s Xi Jinping visited the Maldives in 2014; the Maldives joined PRC’s BRI, borrowed between US$ 1.5 bn to 3 bn; passed new laws that allowed foreigners including Chinese nationals to own lands; signed new mega-infrastructure projects, a Free Trade Agreement, etc; and even decided to build an observatory post in the Indian Ocean.

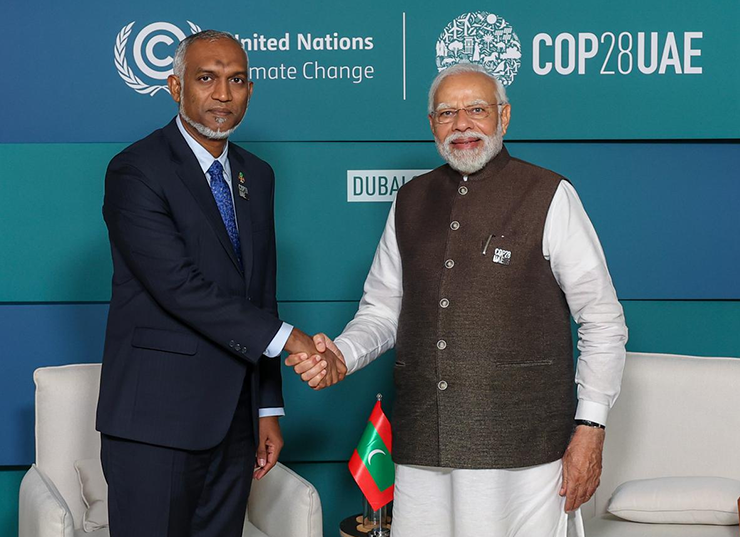

After the MDP-led coalition under President Solih assumed power in 2018, an “India First” policy was given primacy and ties with Beijing were downgraded. However, the MDP-led coalition did not sever ties with the PRC, but continued cooperating with Beijing on various issues (e.g., sports, infrastructure projects, energy sector, etc.) while respecting Indian sensitivities.

Beijing’s interest in the Maldives is dictated primarily by its desire to establish a military base there, and that PRC’s development of port infrastructure under its ‘String of Pearls’ in India’s immediate neighbourhood is part of that plan. Unfortunately, these conjectures extrapolate directly, but unthinkingly, from the USA’s model of military basing worldwide

Assessment

Playing Adversaries: Marginal countries like the Maldives have learnt the art of manipulating geopolitical adversaries by playing on their strategic concerns and fears. A particular regime overtly leans one way to obtain funding and support for contesting the elections, and extracting financial and infrastructural commitments from one side; the next leans the other way to obtain equivalent or better support and investments. All this helps the incumbent political leaders to deliver prosperity to their constituents without taxing them or using their country’s limited revenues. In addition are covert bribes paid to their leaders to side with a particular nation. Thus, there appear to be no real ideological underpinnings that tie a political party to a particular nation – they will conveniently side with who will benefit them personally and politically – and this is apparent from the fact that the geopolitical pendulum has swung with each presidential election. The question is whether India should participate perpetually and wholeheartedly in this mug’s game. The PRC, with a far larger economy and resources, has a much larger geopolitical canvas to cover and the Maldives is just one part of it. The Maldives on the other hand, is far more dependent on nearby India – and instead of trying to constantly outbid the PRC, India needs to play a nuanced, strategic game, with quiet diplomacy being given primacy.

Economic and Political Risk: The PRC undoubtedly has far deeper pockets on account of its larger economy, and thereby, a capability to outdo India financially. However, it needs to be noted that the Maldives’ economy is not in a great state and the economic woes forecast by the World Bank are expected to ascend during Dr Muizzu’s presidency. This is perhaps one reason for Dr Muizzu’s tilt towards the PRC. Besides, the main driver of the pro-PRC policy was Abdulla Yameen, who is still in jail. It remains to be seen whether Dr Muizzu will bail out Yameen and risk a situation like what happened with the MDP (Nasheed convicted; Solih propped to contest for the presidency; Nasheed returns after courts overturn his conviction, appointed Speaker; relations between Nasheed-Solih sour). Thus, given the country’s ties with India and the USA, it is unlikely that Dr Muizzu’s coalition government will adopt an all-out, abrasive, anti-India stance. This suspension of the Maldivian deputy minister who made derogatory remarks indicates that Dr Muizzu’s government may not be willing to burn bridges with India.

Considering the physical proximity of the Maldives to India, Washington’s ongoing engagement with the Maldives and China’s own imperatives, building a wartime military facility in the Maldives is unlikely to be a Chinese priority in the near future, as any attempt to establish one will face a tremendous pushback from the USA

Contours – Military Threat From PRC

- Broadly, there are two categories of basing arrangements. One is peacetime basing; this involves operational turnaround of military vessels at ports of other nations, and is something almost every navy does. The other is wartime basing; in this, the military base, wholly operated by the parent country in a host nation, is expected to provide a capability to support military operations from that base. By corollary, any military base built in a foreign country for wartime support must be capable of fending off a military strike by an adversarial nation. This requires space, troops and associated weaponry. It also needs to be noted that any nation that provides basing and/or operational turnaround to warships of a country involved in a war, becomes a party to the conflict.

- One part of the ‘China Threat’ has its premise in ‘conventional wisdom’ that Beijing’s interest in the Maldives is dictated primarily by its desire to establish a military base there, and that PRC’s development of port infrastructure under its ‘String of Pearls’ in India’s immediate neighbourhood is part of that plan. Unfortunately, these conjectures extrapolate directly, but unthinkingly, from the USA’s model of military basing worldwide. The reality is that the US military enjoys a massive conventional-forces overmatch over its nearest adversary, has established numerous military bases over a period of time, and most importantly, has the military bandwidth to defend most of its bases. It also has overwhelming capacity for, and experience in expeditionary operations.

- Any Chinese base in the immediate vicinity of India, particularly in the Maldives (or Sri Lanka) will be within striking range of India’s military whose capability is significant – and therefore, the PRC will require a substantial capability to defend it from air and sea-borne attacks. Notably, there are no signs of such plans. In contrast, PRC’s sole military base, in Djibouti, is located a few kms away from the US permanent military’s base, Camp Lemonnier – and will be useless in the event of a war with the USA. Besides, in India’s neighbourhood, the Indian military, operating off the Indian landmass, holds the ‘home theatre advantage’ vis-à-vis PRC on account of the proximity of the Indian landmass.

- Therefore, to set up and sustain a viable wartime base in the Maldives, the PLA would need to build an overwhelming force capability at that base to protect it from air and sea-borne attacks. For this, the PLAN would require a much larger force structure than what it has now. Importantly, the geography between PLAN’s home ports in PRC in the South and East PRC Seas, and any PLAN fleet/ships stationed in the IOR makes it difficult to defend Chinese home waters and simultaneously conduct major combat operations across the Malacca Strait in the Indian Ocean. It also needs to be noted that the southernmost island of the Andaman & Nicobar archipelago is situated above the mouth of the Malacca chokepoint – and which can be utilised effectively to thwart the movement of PLAN ships into the IOR. In sum: the PLAN presently lacks the capability to defend a military base in IOR in case of hostilities.

- In the absence of such a capability, it makes better sense for the PRC to set up a military base in a country that is its strategic ally, is inimical to India, has a strong military, and can contribute to the defence of that Chinese military base. Pakistan, a client-state, and Gwadar, located at the furthest end of Pakistan, fit this requirement ideally. Alternatively, the PRC can set up a base away from easy military reach, e.g., in Seychelles. It would be recalled that in December 2011, Seychelles, ostensibly in response to Chinese overtures, had invited the PRC to set up a military base, but later clarified that it would only extend operational turn-around facilities to PLAN, as is being done for other friendly countries.

Colombo Security Conclave (comprising India, Sri Lanka, the Maldives, Mauritius, Bangladesh and the Seychelles) should be strengthened in terms of maritime security and development of a ‘Blue Economy’. Besides, the Maldives should be included as an Observer in ‘The Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation’ (BIMSTEC).

- In sum: considering the physical proximity of the Maldives to India, Washington’s ongoing engagement with the Maldives and PRC’s own imperatives, building a wartime military facility in the Maldives is unlikely to be a Chinese priority in the near future, as any attempt to establish one will face a tremendous pushback from the USA. However, the PRC is expected to enhance its economic and cultural influence in the island nation in the hope of establishing peacetime operational turnaround facilities to support its naval and economic operations in the IOR, particularly to support the BRI. Most importantly, India has an alternative to the Maldives – the Lakshadweep Islands, which it can develop as a military outpost.

Tourism: The Communist Party of China (CCP) has been using ‘Approved Destination Status’ (ADS) to regulate tourism in various countries. The Maldives was first granted ADS in 2002. During Nasheed’s presidency (2008-2012), the PRC had threatened to remove the Maldives’ ADS due to “negotiations between Malé and Washington to allow suspected Uyghur terrorists detained at Guantanamo Bay to be resettled in the Maldives”. India could also use its LTC programme to upgrade or regulate Indian tourism to the Maldives.

Multi-National Forums: Colombo Security Conclave (comprising India, Sri Lanka, the Maldives, Mauritius, Bangladesh and the Seychelles) should be strengthened in terms of maritime security and development of a ‘Blue Economy’. Besides, the Maldives should be included as an Observer in ‘The Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation’ (BIMSTEC).

Overall, given the delicate security challenge a Chinese presence in the Maldives poses to Indian strategic interests, there is a need for a balanced, sustained engagement, and nuanced defence and foreign policy response, as opposed to knee-jerk reactions and mindless trolling to Maldivian utterances and perceptions.

-The writer is a former Principal Director, National Security Council Secretariat. He has also served as Director (Intelligence Coordination), Defence Intelligence Agency in its founding years, and also as Senior Consultant in the NDMA, MHA. The views expressed are personal and do not necessarily reflect the views of Raksha Anirveda