Ukraine’s Defence Minister, Oleksii Reznikov recently said that the General Staff of the Armed Forces of Ukraine is planning a counter-offensive on several fronts, but it completely depends on weather conditions. According to the minister, Ukrainian soldiers are also awaiting for the correct moment, which is likely to arrive in May or later. This is because the land is very wet during spring, which implies that the armed forces are mostly limited to the use of tracked vehicles.

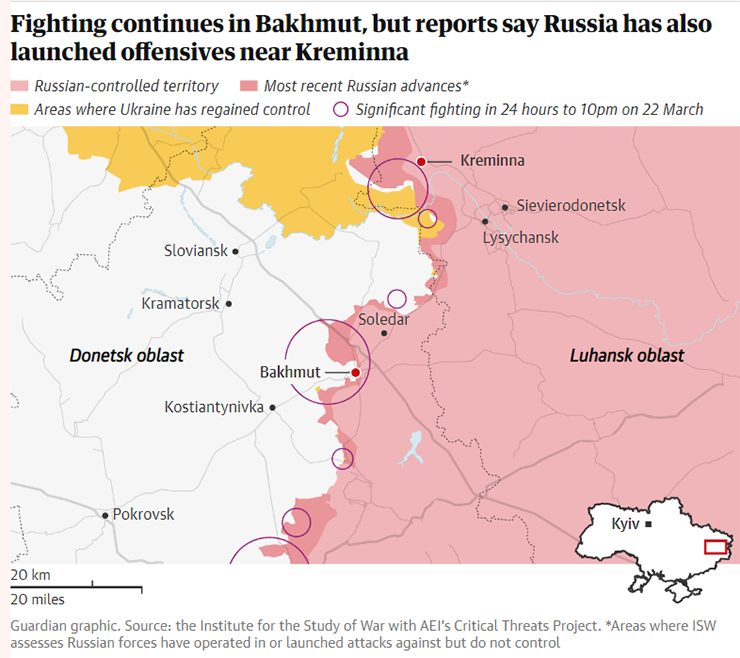

On Bakhmut, Reznikov added that Kyiv’s troops have significantly diminished Moscow’s offensive capacity in that sector. In his view, this will assist Ukraine’s defence forces to “keep the frontline stable and buy time to prepare for the counter-offensive.”1 As per the Deputy Chief of Defence Intelligence of Ukraine, Vadym Skibitskyi, while one of the strategic aims of the counter-offensive will be to “drive a wedge into the Russian front in the south – between Crimea and mainland Russia”,2 the precise timing of the offensive will depend on many elements, including the arrival of Western munitions.

What is Maskirovka?

Even with Ukraine’s forces gradually receiving previously pledged western tanks, infantry fighting vehicles and other armaments, suggestions by Kyiv’s top brass of a counterattack in or around Bakhmut itself appear incredible, however.

Though a counter-strike is expected, Bakhmut is not the sensible location for it, given that the city only possesses limited military value. The main benefit for Kyiv to protect it is on the premise that doing so will ultimately impose a curb on the Russian attack, and return the initiative to the Ukrainian forces.

As per western estimates, Russian casualties in pursuit of Bakhmut number between 20,000 and 30,000. Though it has been claimed that Kyiv’s forces have been suffering fewer losses, it is often seen that Ukraine has been losing some of its elitist troops against erstwhile prison inmates recruited by the Wagner paramilitary outfit. A yet bigger risk is that Russian forces surround Bakhmut, rendering multiple Ukrainian brigades trapped in the city, which could compel Kyiv to use its western tanks to extricate them.

A likelier possibility is that Ukraine’s top brass engages in some plain misleading – a type of Maskirovka – a Soviet military concept that includes western ideas of operational covertness with straightforward deception. Moscow’s defence bloggers, probably proxies for its important commanders, are increasingly preoccupied with the potential locations for a Ukrainian spring counter-offensive.3 Even a mention of the same, in respect of Bakhmut, maintains the possibility.

Recent Russian media reportage hints toward some consternation. The state-run TASS news agency recently reported the chairman of the “We Are Together with Russia” grouping in the Russian-held southern Ukrainian regions as claiming that Kyiv had mobilised about 75,000 soldiers on the Zaporizhzhia front in southern Ukraine. Notably, another TASS report indicated an increasing Ukrainian artillery build-up along the eastern Donbas front.

For its part, Kyiv’s military command has proven proficient at hiding its objectives. Last September, the long-anticipated and much-acclaimed Ukrainian advance toward Kherson – eventually vacated by Russian forces last November – was eclipsed by a shock thrust in the north-eastern Kharkiv region, which collapsed Russian lines and sent Moscow’s unsuspecting units beating a hasty retreat.4

Mark Voyger, a non-resident senior fellow at the Centre for European Analysis and professor at the American University of Kyiv, expects the Ukrainians to replicate a similar disinformation operation. However, he feels on the flip side that the heightened anticipation and discourse surrounding the envisaged offensive would make successful execution harder for Kyiv. “At the same time, maybe this saturation of this information space with so much comment, conjecture, and analysis, also creates a ‘white noise’” which may assist Kyiv in hiding its intentions and throwing the Russians off balance, in his view.5

Russian Defences

Russian defensive lines in the Donbas are more substantial than those in the south, and a Ukrainian thrust there would consequently be perilous, though maybe less so if Russian units in the region have been adequately weakened by the pitched battles in flashpoints like Bakhmut, Kreminna, Avdiivka and Svatove. Numerous hilltop fortifications surrounded by networks of defensive lines exist on both sides of the frontline, making offence much harder than defence for either side.

The plain terrain in Kherson and Zaporizhzhia Oblasts (provinces) seems more favourable for Ukrainian tanks that have witnessed little action in the clashes around Bakhmut, which has overwhelmingly been fought using artillery and infantry – both mechanised and non-mechanised. Although Russian forces there have been entrenching themselves, they have only had a limited window to prepare defences in comparison to their comrades in the east.

Kyiv’s Options

There are no simple choices for Kyiv, however. Attacking across the Dnieper River in Kherson Oblast, or advancing toward Enerhodar across the Kakhovka Reservoir are both extremely risky propositions. Alternatively, conducting counter-thrusts in highly built-up population centres such as in Donetsk or Horlivka would likely turn into protracted and attritional affairs.

Military observers feel that Ukraine may use Maskirovka – a Soviet military concept that includes western ideas of operational covertness with straightforward deception

In theory, a southward thrust from Zaporizhzhia toward Melitopol and the Sea of Azov coastline seems the most preferable, as this would divide the Russian forces in Ukraine into two disjointed groups – one in the east and the other in the south – with the latter becoming much more endangered logistically because the only remaining logistics channel would pass through the Crimean bridge. Then if the bridge was to be successfully targeted again, it could cause significant difficulties to the Russians. But the Kremlin is completely cognisant of this possibility especially after last year’s bombing, and has tightened security there.

Russia’s Minister of Transport Vitaly Savelyev recently reported to President Putin that each vehicle crossing the Kerch Bridge is checked.6 The minister further stated that by summer, the number of personnel conducting transportation through the Kerch Straits, including its security, would be raised.

Since the bridge was attacked last year, it has been repaired and explosives – especially nitrogen fertilisers – are transported through the Kerch Straits only by ferries.7 In fact, many tankers carrying liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) have been stopped from crossing under the bridge due to security curbs imposed by Moscow in recent times, and exporters from Russia and Kazakhstan have had to divert their cargoes from Temryuk.8

Therefore, from Kyiv’s standpoint, the expected gains from a drive toward the Sea of Azov are diminished to the extent that Moscow can sustain supplies to its forces in the south of Ukraine through the Kerch Bridge, even if the advancing Ukrainian troops successfully reach the coast.

References

- Counter-offensive to be conducted on several fronts and could start in April or May – Ukraine’s Defence Minister (yahoo.com)

- Ukrainian intel officer reveals liberation plans for spring – Ukraine news / The New Voice of Ukraine (nv.ua)

- Ukrainian top brass stirs the pot with talk of Bakhmut counterattack | Ukraine | The Guardian

- Ukraine Leaders Eye Maximalist War Goals as Russian Lines Collapse (newsweek.com)

- Where Will Ukraine’s Counteroffensive Happen? (newsweek.com)

- Минтранс сообщил о 100-процентом досмотре транспорта на Крымском мосту – РИА Новости, 25.03.2023 (ria.ru)

- 100% inspection of transport provided on the Crimean Bridge | The Eastern Herald

- Gas cargoes stranded near Russia due to Crimea bridge security restrictions | Al Arabiya English

-The author is serving as a Fellow at Observer Research Foundation. Views expressed are personal and do not necessarily reflect the views of Raksha Anirveda

The writer is an independent researcher with publications spanning diverse fields, including terrorism and counter-terrorism, foreign policy, climate finance, microfinance, maritime security, corporate finance, and industrial organisation.