Defence budgeting is not an annual financial ritual. It is a strategic signal. It communicates national intent to adversaries, reassurance to citizens and direction to the armed forces. The Defence Budget 2026, presented at a time of accelerated threat convergence, therefore warrants assessment not merely for what it allocates, but for what it enables in terms of capability, credibility and deterrence.

The Indian armed forces today confront a spectrum of challenges unprecedented in simultaneity and complexity. Conventional deterrence along contested land borders now coexists with maritime competition, cyber vulnerability, space dependence and information warfare. Operation Sindoor demonstrated how rapidly escalation thresholds are compressing, warning times are shrinking, and decision cycles are shortening. In such an environment, capability gaps no longer remain theoretical. They translate directly into operational risk and strategic vulnerability.

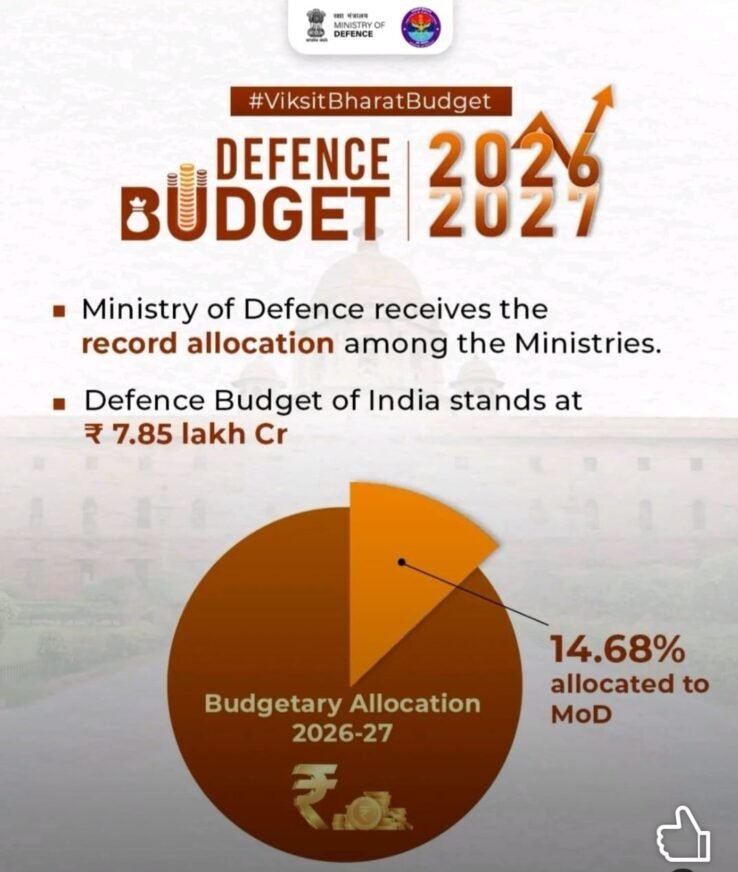

The 2026 defence allocation of ₹7,84,678 crore reflects a 15.2 per cent increase in absolute terms, particularly in capital outlay to ₹2.19 lakh crore (increase 22 per cent), signalling recognition of modernisation imperatives. However, when examined through a capability lens rather than headline figures, enduring structural constraints limit its transformational impact. The issue is not intent, but sufficiency, sequencing and alignment with the character of future warfare.

The most persistent challenge remains the dominance of revenue expenditure at ₹5,53,668 crore (70.56per cent). Personnel costs and pensions are integral to maintaining a young, professional and physically capable force. They are not dispensable, nor should they be framed as inefficiencies. Yet their scale restricts fiscal space for future capability creation. Even after enhancement, the capital component remains inadequate relative to the pace of technological disruption underway in military affairs.

Revenue expenditure supports pay, allowances and operational sustenance. The revenue-to-capital ratio stands at 68:32 from 63:37 in the previous year, which is adverse and impacts modernisation. The ratio of Capital Outlay to Revenue Expenditure (excluding pensions and civil) is approximately 0.60:1. When considering the total revenue-related burden (including pensions), the share of capital expenditure in the total Ministry of Defence budget is approximately 27.95 per cent, while revenue-related costs (sustenance, salaries, and pensions) account for nearly 68 per cent.

The 2026 defence allocation of ₹7,84,678 crore reflects a 15.2 per cent increase in absolute terms, particularly in capital outlay to ₹2.19 lakh crore (increase 22 per cent), signalling recognition of modernisation imperatives. However, when examined through a capability lens rather than headline figures, enduring structural constraints limit its transformational impact. The issue is not intent, but sufficiency, sequencing and alignment with the character of future warfare

Modernisation today is no longer platform-centric. It is architecture-system centric. Network resilience, sensor fusion, secure communications, cyber defence, space situational awareness and autonomous decision-support systems increasingly define combat effectiveness. These capabilities demand sustained investment, compressed procurement cycles and close integration between operators, scientists and industry. Annual budget variability and fragmented allocations are structurally misaligned with these requirements.

While capital allocations have increased by 22% and the modernisation budget is at Rs 1.85 lakh crores, committed liabilities continue to absorb a significant portion, reducing flexibility to induct emerging technologies at scale. Legacy acquisition processes, despite reform, remain mismatched with innovation cycles. Without protected funding mechanisms for disruptive technologies, the armed forces risk technological lag despite numerical adequacy and force size.

Indigenisation remains central to long-term operational resilience. Rs 1.39 lakh crore, i.e., 75% of the Capital Acquisition budget, has been allotted for procurement through domestic industries during the FY 2026-27, reinforcing Aatmanirbhar Bharat and strengthening private sector participation. Supply-chain security, wartime sustainability and strategic autonomy depend on domestic industrial depth. Progress over the past decade is tangible. Private-sector participation has expanded, defence exports have grown, and production capacity has improved. Yet the ecosystem remains uneven. Tier-2 and Tier-3 suppliers continue to struggle with demand predictability, payment delays and risk exposure, limiting their ability to scale, innovate and invest in advanced manufacturing.

Defence research and development is the critical enabler in this equation. Current allocations, though incrementally increased, remain insufficient to generate indigenous intellectual property in propulsion, sensors, electronic warfare, artificial intelligence, quantum technologies and other emerging domains. Without a decisive shift in R&D funding and deeper integration with private industry and academia, innovation risks remaining incremental rather than disruptive. Future military credibility will belong to those who control core technologies, not merely those who assemble systems.

A further strategic gap lies in the absence of a formally articulated National Security Strategy and an institutionalised defence review mechanism. Capability development without transparent threat prioritisation leads to fragmented resource allocation and suboptimal sequencing. A published strategy would enable coherent joint planning, guide procurement priorities and provide the industry with long-term visibility. It would also strengthen civil-military alignment, which remains essential for sustained transformation.

Modernisation today is no longer platform-centric. It is architecture-system centric. Network resilience, sensor fusion, secure communications, cyber defence, space situational awareness and autonomous decision-support systems increasingly define combat effectiveness. These capabilities demand sustained investment, compressed procurement cycles and close integration between operators, scientists and industry. Annual budget variability and fragmented allocations are structurally misaligned with these requirements

Jointness and integration are recurring themes in India’s defence reforms. Theatre commands, data-centric operations and cross-domain synergy are no longer optional doctrinal choices. However, organisational reform must be matched by financial empowerment. Joint capabilities often fall between service-specific budget silos, diluting accountability and slowing execution. Dedicated funding for joint and cross-domain capabilities would address this systemic weakness and accelerate operational integration.

Infrastructure development by way of allocation to BRO along land borders and in the maritime domain represents a clear positive. Improved mobility, logistics and surveillance enhance deterrence and operational responsiveness. Investments in border roads, island territories and the Coast Guard strengthen India’s posture across multiple theatres and directly support contingency readiness.

Human capital remains the armed forces’ greatest strength. However, technology absorption demands continuous skill upgradation, doctrinal evolution and cultural adaptation. Budgetary provisions must therefore support training, experimentation, simulation and concept development alongside equipment induction. Capability is as much about integration and employment as it is about acquisition.

Defence budgeting must also be viewed through the prism of deterrence credibility. Adversaries assess intent through sustained investment patterns, not rhetoric. A defence allocation that remains static as a share of less than 2% of GDP (including pensions, else much lesser) despite rising threats and risks signalling complacency. A calibrated progression towards a higher GDP share of 2.5 to 3 per cent, excluding salaries and pensions, would reinforce deterrence without destabilising fiscal balance.

Beyond immediate budgeting choices lies a deeper doctrinal shift. Defence budgeting must be anchored in national strategy rather than annual arithmetic. Emerging strategic thought points towards a transition from import substitution to strategic resilience and ultimately to strategic indispensability. In an era defined by geopolitical fragmentation, contested supply chains and technology denial regimes, economic security has become a determinant of military power. Defence preparedness is inseparable from industrial capability and technological sovereignty.

For the armed forces, this shift has direct operational implications. Sustained import dependence erodes readiness and wartime resilience, while inward-looking self-sufficiency limits technological depth. The strategic objective must be to position India as a non-substitutable node in global defence value chains, ensuring assured access, resilience and influence. Defence manufacturing must therefore be treated as strategic infrastructure that underpins deterrence and warfighting sustainability.

A further strategic gap lies in the absence of a formally articulated National Security Strategy and an institutionalised defence review mechanism. Capability development without transparent threat prioritisation leads to fragmented resource allocation and suboptimal sequencing. A published strategy would enable coherent joint planning, guide procurement priorities and provide the industry with long-term visibility

Strategic relevance in the Indo-Pacific will accrue to nations that shape interconnected supply ecosystems rather than withdraw from them. India must pursue structured co-production and co-development partnerships with trusted partners such as the United States, France, the United Kingdom, Israel and Japan. Technology transfer must be embedded in long-term manufacturing relationships rather than confined to licensed production. Indigenous capability must grow through a balanced ecosystem where private industry scales alongside defence public sector undertakings, while exports provide scale, cost efficiencies and global credibility.

Manufacturing discipline is central to combat readiness. Advanced manufacturing standards, stringent quality assurance and targeted incentive frameworks for defence electronics and critical components are essential. Supply-chain resilience requires reducing single-source dependencies through domestic production of semiconductors, advanced materials, propulsion systems and rare-earth-based inputs. Defence research must be structured to generate dual-use outcomes, ensuring that investments in aerospace, artificial intelligence, robotics and electronics strengthen both military and civilian capability bases.

Financial allocations alone will not deliver transformation. State capacity remains the critical constraint. Procurement processes must be simplified to enable multi-year contracting, predictable demand and faster induction cycles. Decision-making timelines must compress to exploit opportunities created by global supply-chain realignments. Institutional mechanisms are required to enable professional risk-taking, clearly distinguishing bona fide judgment from procedural failure. Regulatory streamlining to facilitate private-sector entry and scale is essential.

The global security environment reinforces these imperatives. Rising conflict intensity and multi-domain warfare across cyber, space and the electromagnetic spectrum demand modern, well-resourced forces supported by frugal, mission-specific artificial intelligence and secure digital architectures. Export controls and technology restrictions further strengthen the case for indigenous capability anchored in global integration rather than import reliance.

India’s macroeconomic strength provides the foundation for this approach. Sustained growth, fiscal discipline and manageable inflation create space for consistent defence capital expenditure, higher research investment and multi-year procurement commitments without undermining developmental priorities.

Financial allocations alone will not deliver transformation. State capacity remains the critical constraint. Procurement processes must be simplified to enable multi-year contracting, predictable demand and faster induction cycles. Decision-making timelines must compress to exploit opportunities created by global supply-chain realignments

No defence budget can meet every operational aspiration. Constraints are inevitable. Yet prioritisation itself is a strategic act. Defence Budget 2026 reflects continuity and caution. What it now requires is complementarity through reform: non-lapsable modernisation funds, accelerated procurement pathways, realistic risk-sharing with industry and protected R&D allocations.

Preparedness carries a cost, but unpreparedness carries far greater consequences. The armed forces do not seek extravagance. They seek credibility, predictability, and the means to prevail across domains. Defence Budget 2026 provides a foundation. Whether India moves decisively from resilience to indispensability will determine the credibility of its military power in the decade ahead.

The author, a PVSM, AVSM, VSM has had an illustrious career spanning nearly four decades. A distinguished Armoured Corps officer, he has served in various prestigious staff and command appointments including Commander Independent Armoured Brigade, ADG PP, GOC Armoured Division and GOC Strike 1. The officer retired as DG Mechanised Forces in December 2017 during which he was the architect to initiate process for reintroduction of Light Tank and Chairman on the study on C5ISR for Indian Army. Subsequently he was Consultant MoD/OFB from 2018 to 2020. He is also a reputed defence analyst, a motivational speaker and prolific writer on matters of military, defence technology and national security. The views expressed are personal and do not necessarily carry the views of Raksha Anirveda