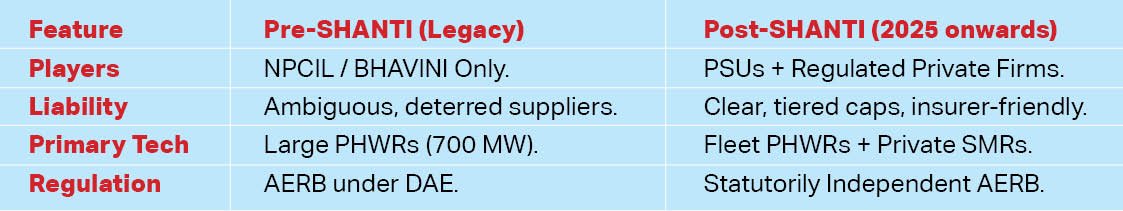

The global energy landscape is undergoing tectonic shift. As the climate crisis intensifies, nations are moving beyond the “intermittency” of solar and wind toward stable, high-density energy sources. In December 2025, India signalled its entry into this new era with the passage of the Sustainable Harnessing and Advancement of Nuclear Energy for Transforming India (SHANTI) Bill. Replacing the decades-old Atomic Energy Act of 1962 and the Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage Act of 2010, the SHANTI Bill is not merely a legal update – it is a manifesto for India’s energy independence. By opening a once-impenetrable state monopoly to private participation and streamlining liability, the Act seeks to propel India toward a massive 100 GW nuclear capacity by 2047.

The Current State of Nuclear Energy in India

As of late 2025, India’s nuclear sector is in a state of “contained potential”. For the past sixty years, the sector was the exclusive preserve of the Department of Atomic Energy (DAE) and the Nuclear Power Corporation of India Limited (NPCIL). India currently operates 25 reactors across 7 plants, with an installed capacity of approximately 8.8 GW. While this represents only about 3.1% of India’s total electricity mix, nuclear power serves as a critical “baseload” source that runs 24/7, unlike weather-dependent renewables.

India remains committed to Homi Bhabha’s visionary three-stage programme, designed to eventually utilise India’s vast Thorium reserves. The recent commissioning of the Prototype Fast Breeder Reactor (PFBR) at Kalpakkam marks the transition into the second stage. India has perfected the 700 MWe Pressurised Heavy Water Reactor (PHWR) design, which is now being deployed in “fleet mode” (10 reactors at once) to achieve economies of scale.

For the first time since Independence, private companies are allowed to build, own, operate, and decommission nuclear power plants. Private entities can hold up to 49% equity in nuclear projects, ensuring that while private capital drives efficiency, majority control remains with the state to protect national security

Key Provisions of the SHANTI Bill, 2025

The SHANTI Bill introduces three revolutionary structural changes to the nuclear ecosystem of India:

Private Sector Participation

For the first time since Independence, private companies are allowed to build, own, operate, and decommission nuclear power plants. Private entities can hold up to 49% equity in nuclear projects, ensuring that while private capital drives efficiency, majority control remains with the state to protect national security.

The Rise of Small Modular Reactors (SMRs)

The Bill places a heavy emphasis on SMRs – reactors with a capacity of less than 300 MW. Unlike giant traditional plants that take decades to build, SMRs are factory-built, mobile, and can be deployed as “captive” power plants for heavy industries like steel and aluminium, aiding in industrial decarbonisation.

Liability Reform and Regulatory Autonomy

The Bill overhauls the contentious “supplier liability” clause that had long deterred foreign vendors like GE and Westinghouse to come to India. It shifts the primary financial burden to the operator through a tiered liability cap (up to ₹3,000 crores) while granting statutory independence to the Atomic Energy Regulatory Board (AERB), separating the “safety referee” from the “policy player.”

The Pros: Why Nuclear? Why Now?

The rationale behind the SHANTI Bill rests on several strategic pillars:

- Energy Security: As India aims for a $5 trillion (and eventually $30 trillion) economy, its energy demand is projected to double. Nuclear energy provides a stable, high-capacity factor (often >80%) that coal currently provides, and that too without the carbon footprint.

- Net-Zero Commitments: To reach Net-Zero by 2070, India must retire its aging coal fleet. Nuclear is the only carbon-free source capable of providing massive blocks of power for the national grid.

- Technological Hub: By fostering a domestic private ecosystem, India aims to become a global hub for SMR manufacturing, potentially exporting “Bharat Small Reactors” to other developing nations.

The SHANTI Bill aligns India with global trends seen in the US (SMR development) and France (Nuclear Renaissance). However, India’s model is unique in its “Hybrid Governance.” Unlike the fully privatised model in the US or the state-centralised model in Russia, India is attempting a middle path, i.e. State-supervised Private Operations

The Cons: Critical Challenges and Critiques

Like most opponents of the Bill, INC MP Shashi Tharoor’s focused on the structural ambiguity of the bill and the inherent risks of a profit-driven nuclear cycle.

The “Unclear” Bill: Tharoor famously quipped, “I am not sure whether it is a nuclear bill or an unclear bill,” targeting the heavy use of discretionary powers granted to the central government and the lack of precise legislative language.

The Profit-Safety Conflict: Tharoor warned that opening the entire fuel cycle – from mining to waste management – to private players with “indeterminable qualification criteria” would lead to safety compromises. He argued that firms driven by “quarterly earnings” could not be trusted with the thousand-year risks of radioactive materials.

The “Trapdoor” Liability: Tharoor compared the bill’s $460 million (₹3,910 crore) liability cap to global disasters like Fukushima ($182 billion) and Chernobyl ($700 billion). He termed the cap a “trapdoor for victims” rather than a safety net, arguing that the limit is lower than the compensation paid for the Bhopal Gas Tragedy 40 years ago.

Misleading “Green” Narrative: Tharoor further challenged the preamble’s description of nuclear as “clean and abundant,” noting that the full life cycle, including mining and waste disposal, remains environmentally hazardous and unsustainable.

The SHANTI Bill has also faced significant academic and political pushback:

Safety and Transparency: Section 39 of the Bill has been criticised for overriding the Right to Information (RTI) Act, allowing the government to classify wide swathes of nuclear data as “restricted.” Critics argue that in a post-Fukushima world, nuclear safety requires more transparency, not less.

The Liability “Safety Net”: Critics argue that by capping operator liability and diluting supplier accountability, the state is effectively “privatising profits and socialising risks.” In the event of a catastrophic accident, the financial burden beyond the cap would fall on the Indian taxpayer.

High Capital Intensity: While SMRs are cheaper than large plants, nuclear energy still requires massive upfront investment compared to solar power. Private players may be hesitant to enter without guaranteed “Power Purchase Agreements” (PPAs) that ensure long-term profitability.

The success of the SHANTI Bill will not be measured in Megawatts alone. It will be measured by the government’s ability to maintain a rigorous, transparent safety culture that commands public trust. The “Shanti” (Peace) in the Bill’s name must be reflected in the security and confidence it provides to the citizens living in the shadow of these new reactors

Waste Management: India still lacks a permanent Deep Geological Repository for high-level radioactive waste. Opening the sector to private players without a finalised waste-disposal roadmap raises long-term environmental concerns.

Comparative Analysis: India vs. The World

The SHANTI Bill aligns India with global trends seen in the US (SMR development) and France (Nuclear Renaissance). However, India’s model is unique in its “Hybrid Governance.” Unlike the fully privatised model in the US or the state-centralised model in Russia, India is attempting a middle path, i.e. State-supervised Private Operations.

A Balancing Act

Overall, the SHANTI Bill, 2025, represents a “forced maturation” of India’s nuclear sector. It acknowledges that the state alone cannot fund the $26 billion investment required to meet 2047 targets. By inviting the private sector, India is betting on the same spirit of innovation that transformed its telecom and space sectors.

However, the success of the SHANTI Bill will not be measured in Megawatts alone. It will be measured by the government’s ability to maintain a rigorous, transparent safety culture that commands public trust. The “Shanti” (Peace) in the Bill’s name must be reflected in the security and confidence it provides to the citizens living in the shadow of these new reactors.

India has set the stage; the coming decade will determine if this nuclear leap is a sustainable stride or a leap of faith into a high-risk future.

–The writer is Assistant Professor, ICFAI School of Liberal Arts, ICFAI University, Jaipur. The views expressed are of the writer and do not necessarily reflect the views of Raksha Anirveda