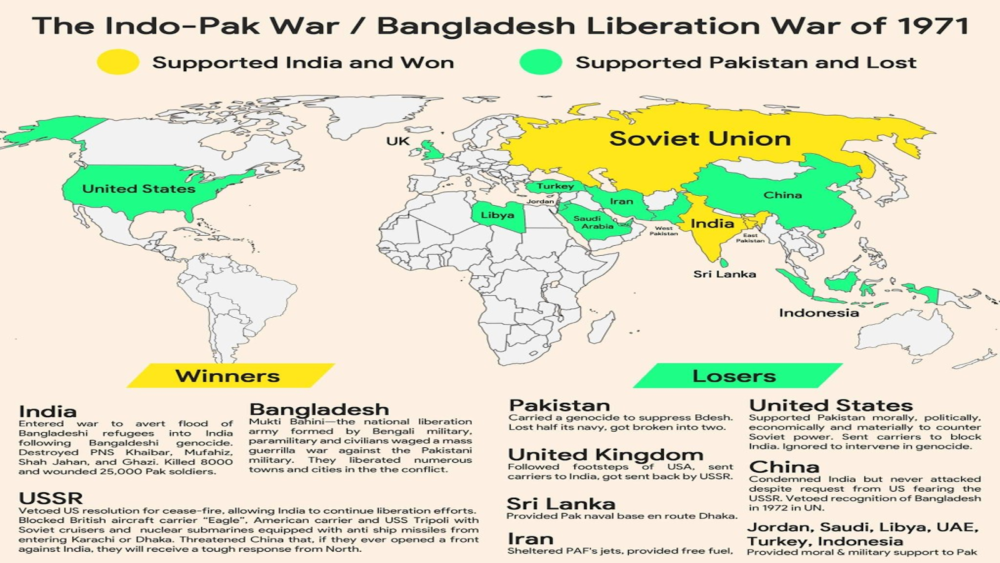

Strategic Context: Why 1971 Was Different: The 1971 conflict did not emerge suddenly. It was the culmination of political repression in East Pakistan following the December 1970 elections, where Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s Awami League won a clear mandate that the military regime in West Pakistan refused to honour. The brutal crackdown launched in March 1971 — Operation Searchlight — triggered a humanitarian catastrophe. Nearly ten million refugees crossed into India, placing immense economic and social strain on border states.

India’s response under Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was notable for its strategic patience. Rather than rushing into war, New Delhi focused on three interlinked objectives:

- Creating international legitimacy for intervention by highlighting the refugee crisis and human rights violations.

- Shaping the battlefield in advance, particularly in the East, through support to the Mukti Bahini.

- Preparing for a short, decisive conflict, minimising the risk of great-power intervention.

This political–military alignment would become a defining feature of the 1971 campaign.

The Eastern Front: A Campaign of Manoeuvre and Psychological Dominance

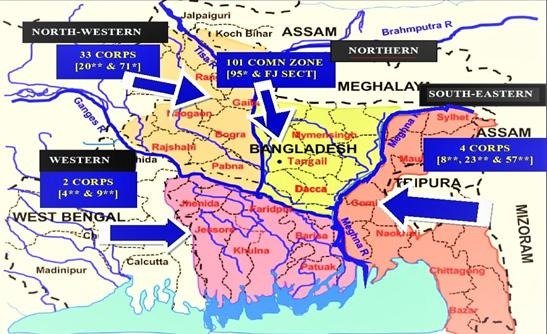

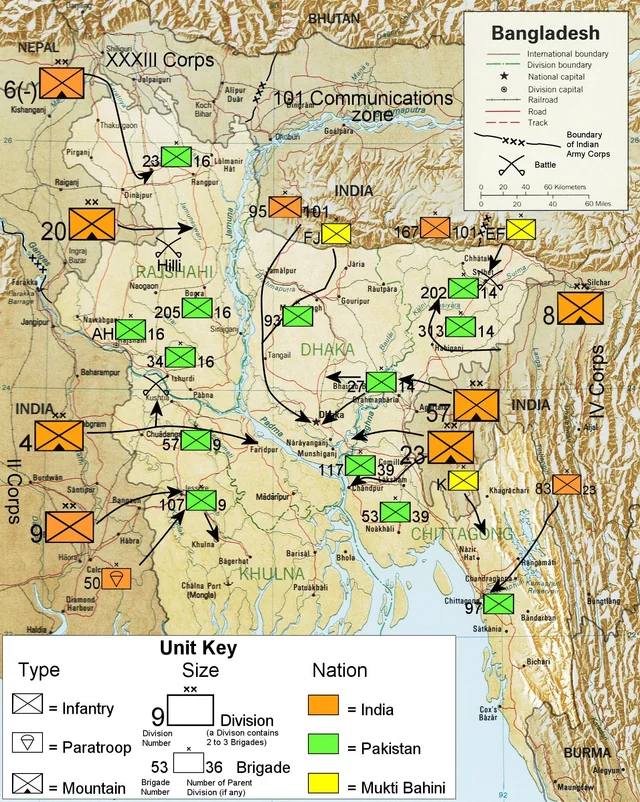

Terrain and Force Balance. East Pakistan presented a unique operational environment: riverine terrain, dense population centres, limited road infrastructure, and a population largely hostile to Pakistani forces. The Pakistan Army had approximately 93,000 troops in the East, dispersed across numerous fortified localities. Indian forces, under Eastern Army Commander Lt Gen Jagjit Singh Aurora. comprised four corps—II, IV, XXXIII, and the newly raised 101 Communication Zone Area, supported by the Mukti Bahini. The Pakistani plan was defensive, based on holding fortified ‘strongpoints’ and awaiting international diplomatic intervention. India, by contrast, adopted a manoeuvre-centric approach aimed at speed, dislocation, and collapse of enemy morale.

Integration of Mukti Bahini: Force Multiplication in Practice. One of the most consequential aspects of the Eastern ground offensive was the integration of the Mukti Bahini with Indian regular forces. By mid-1971, Mukti Bahini units had been trained, armed, and structured to conduct sabotage, intelligence gathering, and guerrilla operations.

One of the most consequential aspects of the Eastern ground offensive was the integration of the Mukti Bahini with Indian regular forces. By mid-1971, Mukti Bahini units had been trained, armed, and structured to conduct sabotage, intelligence gathering, and guerrilla operations

Their contributions were decisive in several ways:

Intelligence dominance: Accurate, real-time information on Pakistani troop dispositions and movement.

Disruption of logistics: Attacks on bridges, ferries, and supply lines isolated Pakistani garrisons.

Psychological warfare: Demonstrated to Pakistani soldiers that they were operating in hostile territory with no popular support.

This synergy reduced the need for costly frontal assaults and accelerated operational tempo.

Corps-Level Advances and the Dash to Dhaka. The Indian plan rejected the traditional method of capturing territory incrementally. Instead, it prioritised bypassing strongholds, isolating them, and driving rapidly towards Dhaka—the political and psychological centre of gravity.

- II Corps advanced from the west, crossing major river obstacles with speed.

- IV Corps attacked from the east, overcoming natural obstacles through bold river crossings.

- XXXIII Corps fixed Pakistani forces in the north, preventing redeployment.

The heliborne operation at Tangail on December 11, 1971, epitomised innovation and audacity. Indian paratroopers cut off Pakistani retreat routes to Dhaka, hastening the collapse of organised resistance. Within thirteen days of the formal outbreak of hostilities, Pakistani forces in the East were encircled, demoralised, and strategically defeated.

The Surrender at Dhaka. On 16 December 1971, Lt Gen A.A.K. Niazi signed the Instrument of Surrender, marking the largest capitulation since the Second World War. The speed of victory — achieved with relatively low casualties — underscored the effectiveness of India’s operational art and civil–military integration.

The Western Front: Holding, Hurting, and Deterring Escalation

While the Eastern Front was decisive, the Western Front played a critical supporting role. Pakistan initiated hostilities in the West with pre-emptive air strikes on December 3, 1971, hoping to relieve pressure on the East and secure limited territorial gains.

India’s Western strategy was deliberately calibrated. The objectives were threefold: Prevent major Pakistani breakthroughs. Inflict disproportionate attrition. Avoid actions that could provoke superpower intervention.

Punjab and Rajasthan: Armour, Infantry, and Combined Arms

In Punjab, Indian forces successfully blunted Pakistani offensives in sectors such as Khem Karan and Fazilka. The Indian Army’s effective use of anti-tank defences and infantry–armour coordination resulted in heavy Pakistani losses.

In the desert sector of Rajasthan, Indian forces advanced towards strategic objectives like Longewala. The Battle of Longewala became emblematic of defensive resilience, where a small Indian force held out against a larger armoured column until air support arrived, destroying Pakistani tanks and halting the advance.

The heliborne operation at Tangail on December 11, 1971, epitomised innovation and audacity. Indian paratroopers cut off Pakistani retreat routes to Dhaka, hastening the collapse of organised resistance. Within 13 days of the formal outbreak of hostilities, Pakistani forces in the East were encircled, demoralised, and strategically defeated

Jammu and Kashmir: Tactical Gains, Strategic Prudence

In Jammu and Kashmir, Indian forces made limited but significant gains, improving tactical positions without overextending supply lines. The emphasis remained on denying Pakistan any decisive success that could offset its impending defeat in the East.

Jointness and Air–Land Synergy

Although this article focuses on ground operations, it is impossible to ignore the role of air power in enabling ground success. The Indian Air Force achieved air superiority early, providing close air support, interdiction, and strategic bombing. In the East, air dominance allowed Indian columns to advance rapidly without fear of aerial interdiction.

This jointness — though less formalised than in modern doctrine — was instinctively practised and proved decisive.

Lessons Learnt: Why 1971 Still Matters

Political–Military Alignment Is Decisive

The 1971 war demonstrated the importance of clear political objectives matched with military strategy. The limited aims in the West and decisive thrust in the East avoided mission creep and ensured coherence.

Speed and Manoeuvre Trump Static Defence

India’s refusal to be drawn into costly battles for fortified positions in the East marked a doctrinal shift. Manoeuvre warfare, targeting the enemy’s centre of gravity, proved decisive.

As India faces a complex security environment marked by hybrid threats, contested borders, and great-power rivalry, the lessons of 1971 remain instructive. Vijay Diwas, therefore, is not merely a commemoration of past glory, but a reminder of what coherent strategy, operational excellence, and national resolve can achieve

Integration of Irregular Forces

The Mukti Bahini experience remains a textbook case of how indigenous resistance movements, when properly integrated, can multiply conventional military power.

Logistics and Planning Are Force Enablers

Extensive pre-war preparation — stockpiling supplies, improving infrastructure, and acclimatising troops — ensured operational momentum. Wars are won as much in logistics depots as on battlefields.

Information and Psychological Warfare Matter

The rapid collapse of Pakistani morale in the East highlighted the role of psychological dominance, popular support, and narrative control—elements even more relevant in today’s hybrid warfare environment.

Limited War Under Nuclear Shadows (A Future Relevance)

Though nuclear weapons were not a factor in 1971, the conflict offers insights into achieving decisive outcomes without uncontrolled escalation — an issue central to contemporary India–Pakistan dynamics.

Strategic Legacy and Contemporary Relevance

The 1971 victory reshaped South Asia, established India as the pre-eminent regional power, and created a sovereign Bangladesh. For the Indian Army, it validated professionalism, adaptability, and ethical conduct in war.

As India faces a complex security environment marked by hybrid threats, contested borders, and great-power rivalry, the lessons of 1971 remain instructive. Vijay Diwas is therefore not merely a commemoration of past glory, but a reminder of what coherent strategy, operational excellence, and national resolve can achieve.

Vijay Diwas 2025 offers an opportunity to revisit the 1971 war not as a static historical episode but as a living repository of strategic wisdom. The ground offensives on the Eastern and Western fronts showcased India’s ability to think holistically, fight jointly, and act decisively

Conclusion

Vijay Diwas 2025 offers an opportunity to revisit the 1971 war not as a static historical episode but as a living repository of strategic wisdom. The ground offensives on the Eastern and Western fronts showcased India’s ability to think holistically, fight jointly, and act decisively. In an era of rapidly evolving warfare, the spirit of 1971 — clarity of purpose, unity of effort, and confidence in national strength — remains as relevant as ever.

-The author retired as Major General, Army Ordnance Corps, Central Command, after 37 years of service. A management doctorate and expert on defence modernisation, he is the author of four books, including the Amazon bestseller “Breaking the Chinese Myth,” and a frequent media commentator. He is affiliated with several leading defence and strategic studies institutions in New Delhi. The views expressed are of the writer and do not necessarily reflect the views of Raksha Anirveda