In May 2009, I was commanding a brigade in Eastern Ladakh. One of my responsibilities was to lead discussions with the People’s Liberation Army at Rezang La, a place where history weighs heavily and silence carries meaning. The meetings were formally termed ‘flag meetings’, but that description has always felt inadequate. These were not negotiations in the classical sense. They were structured conversations with an unsettled line, conducted with ritual courtesy and underlying mistrust.

At the time, I approached those discussions as a professional soldier trained in the logic of confidence-building measures. We were there to maintain calm, prevent escalation, and manage differences. I believed, as many of us did, that time was on our side, that stability, once preserved, would accumulate into understanding. Yet even then, something felt asymmetrical.

Two Militaries, Two Clocks

The Chinese officers across the table were polite, disciplined, and precise. There was no open hostility in their demeanour, no visible aggression, no urgency, no anxiety about reaching any resolution. They spoke as men entirely comfortable with delay, ambiguity, and repetition. What struck me most was not what they said, but what they did not feel compelled to explain. When we referred to earlier agreements, the 1993 and 1996 accords, the established protocols for patrols, the spirit of mutual restraint, their responses were technically correct and strategically empty. They acknowledged the words. They respected the format. But they did not concede the implication that these agreements constrained their actions in the way we assumed they constrained ours. For us, treaties were commitments. For them, they were instruments. That distinction, though not fully articulated in my mind at the time, stayed with me long after my interactions with them at Rezang La.

Rezang La and the Weight of History

Rezang La is not just another feature on the map. It is a reminder of 1962, of sacrifice, of decisions taken far away that played out brutally close to the ground. Standing there in mid-2009, leading discussions meant to preserve peace, I could not escape the awareness that we were speaking across layers of unresolved history. Jawaharlal Nehru famously used the word ‘cheated’ after the Chinese attack in 1962. For years, I understood that sentiment emotionally, even instinctively. But over time, and particularly after Rezang La, I began to see the episode differently. China did not feel it had cheated us. It had acted according to its interpretation of time, power, and obligation.

India interpreted the Panchsheel principles, the absence of a settled boundary, and the rhetoric of brotherhood as a moral constraint; China interpreted them as temporal space: time within which to prepare, consolidate, and act when ready. The sense of betrayal we felt in 1962 stemmed not from duplicity, but from a mismatch of expectations. We believed restraint was reciprocal. China believed restraint was conditional.

Nehru used the word ‘cheated’ after the Chinese attack in 1962, but China did not feel it had cheated us. It had acted according to its interpretation of time, power, and obligation. India interpreted the Panchsheel principles as a moral constraint; China interpreted them as temporal space: time within which to prepare and act when ready

What became clearer to me retrospectively was that China does not treat time as a neutral backdrop against which events unfold. It treats time as part of the environment to be shaped. At Rezang La, the Chinese officers were not impatient to settle patrol disputes. They were not eager to clarify perceptions of the Line of Actual Control. Ambiguity did not trouble them; it was used by them. For us, ambiguity was something to be managed until resolution became possible. For them, ambiguity was leverage. That was the moment, though I did not name it as such then, when I began to understand that we were not engaged in the same long game.

Treaties: Ceiling or Floor

As a brigade commander defending the LAC, I took the agreed CBMs (confidence-building measures) seriously. They mattered because they reduced the risk of tactical miscalculation. They gave commanders space to exercise judgement. They created habits of communication. But in hindsight, I realised that we treated these agreements as ceilings on behaviour. We saw them as lines we should not cross, even when provoked. China treated the same agreements as floors. As long as actions remained below the formal thresholds defined in the text, no firearms, no large-scale deployments, no permanent fortifications acknowledged, there was room to manoeuvre. Patrols could be pushed. Perceptions could be asserted. New normals could be created. At Rezang La, this difference was not yet fully visible on the ground. But it was present in attitude, in how patiently they returned to the same positions, the same claims, the same formulations, meeting after meeting. They were not waiting for time to solve the problem. They were using time to become the solution.

The Illusion of Stability

In 2009, we still believed that limited infrastructure along the LAC was a stabilising factor. We assumed that retaining a degree of difficulty of access would in some way reduce the likelihood of a confrontation. In retrospect, this was a profound misreading of how China looked at the same situation. China had started building relentlessly, roads, tracks, logistics nodes, well away from the glare of crisis. They were not preparing for a war tomorrow. They were preparing so that if that likelihood ever came, it would arrive on their terms. At Rezang La, I saw officers who knew that their system would return them here again and again, better supplied each time. I, on the other hand, knew that my ability to reinforce, rotate, and sustain was constrained, not by will, but by infrastructure. That is when it dawned on me that stability, left unattended, does not preserve balance. It preserves an advantage for the first mover.

Great power competition is often described as a contest of patience. Yet patience alone is not a strategy. The more decisive distinction lies in how time is understood, structured, and weaponised. India and China, despite sharing a long and contested boundary, never played symmetrical long games, not in method, not in tempo, and not in their conception of power itself. Both believed time was on their side, and each used time very differently.

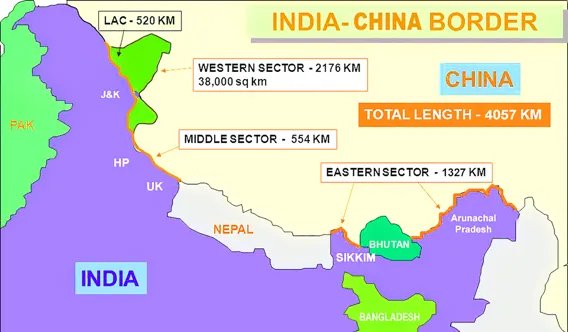

India treated time as a buffer, something that could reduce risk, smooth disputes, and allow our strength to accrue organically. China treated time as an instrument, something to be actively shaped, segmented, and exploited. This divergence, subtle at first, has over the decades produced a strategic asymmetry that now defines the Line of Actual Control (LAC) and much of the broader India-China relationship. This is not a story of Indian blindness versus Chinese brilliance. It is a story of two civilisational states interpreting stability, restraint, and power through fundamentally different lenses, and discovering, too late, that patience without positional advantage is not neutrality, but vulnerability.

Divergent Philosophies of Power and Time

India’s long game was rooted in norms, assuming that stability, once established, would be mutually preserved. That restraint would be reciprocated. That ambiguity, managed through dialogue and confidence-building measures, would reduce incentives for unilateral action. This was a strategic culture shaped by postcolonial caution, economic prioritisation, and an aversion to escalation between nuclear-armed neighbours.

China’s long game was rooted in continuous preparation. China practised the axiom that power had to be accumulated materially and spatially before it could be exercised politically. Stability was not an outcome to be trusted, but a condition to be engineered, and periodically tested. Ambiguity was not something to be resolved, but something to be exploited until it could be replaced by facts on the ground. Where India saw time as something that would naturally reward restraint, China saw time as something that had to be worked upon, layer by layer, kilometre by kilometre, bridge by bridge.

Aksai Chin: Infrastructure Before Explanation

The origins of this asymmetry were clearly visible as early as the early 1950s. Aksai Chin was not merely a territorial dispute; it was a lesson in how China’s long game functioned. For Beijing, the overriding imperative was connectivity between Xinjiang and Tibet. The construction of the G219 highway through Aksai Chin was therefore non-negotiable. It was built quietly, decisively, and without prior diplomatic settlement. By the time India fully grasped its strategic implications, the road already been constructed, not as a proposal, but as a fact. Diplomacy followed infrastructure, not the other way around.

India’s approach, by contrast, rested on assumptions of restraint. The absence of a formally demarcated boundary, coupled with the spirit of Panchsheel, was expected to discourage unilateral actions. India’s long game here was ethical and anticipatory: avoid provocation, trust dialogue, expect reciprocity. China’s long game was cumulative and irreversible. Once the road was built, the strategic debate was effectively over. The 1962 conflict merely formalised a reality that infrastructure had already established. Aksai Chin demonstrated a recurring Chinese pattern: build first, explain later, negotiate only after consolidation.

Infrastructure Asymmetry: Anticipation Versus Inhibition

This pattern repeated itself over decades along the LAC. China invested relentlessly in roads, railways, airfields, logistics hubs, fuel pipelines, and communication networks across Tibet and Xinjiang. These were not crisis-driven responses. They were anticipatory investments, designed for contingencies that China hoped never to fight, but fully intended to dominate if required. Infrastructure for China is and was treated as latent power. India, in contrast, viewed infrastructure through a stabilising lens. For years, limited connectivity along the border was considered a virtue rather than a liability. The belief was that underdevelopment reduced the risk of escalation by slowing mobilisation and signalling restraint. Roads were seen as potential provocations rather than enablers of deterrence. China interpreted the same restraint very differently. Underdevelopment was not stability; it was opportunity.

The result was an enduring asymmetry: In Ladakh and then in Tibet, China could mobilise faster, sustain longer, and posture deeper, often without crossing formal thresholds of conflict. India’s long game assumed peace would be preserved by mutual caution. China’s long game assumed peace would favour whoever arrived first and stayed the longest.

At Rezang La, the Chinese officers were not impatient to settle patrol disputes. They were not eager to clarify perceptions of the Line of Actual Control. Ambiguity did not trouble them; it was used by them. For us, ambiguity was something to be managed until resolution became possible. For them, ambiguity was leverage

Xiaokang Villages: Civilianisation as Strategy

Perhaps the most refined expression of China’s long game along the Line of Actual Control lies in the creation of Xiaokang border defence villages. These settlements were not products of crisis or confrontation; they were conceived and constructed during periods of relative calm. That fact alone is revealing. China has consistently chosen moments of stability to reshape the frontier, using development not as relief, but as strategy. The significance of these villages becomes clearer when one understands the intellectual lineage of the term Xiaokang. Originating in the Book of Songs (Shijing) over two millennia ago, Xiaokang described a condition of “moderate prosperity”, a society marked by order, sufficiency, and harmony rather than excess. In Chinese political thought, the term has always implied more than material well-being; it carries civilisational connotations of hierarchy, collective responsibility, and social discipline. Deng Xiaoping deliberately revived the concept in 1979 to frame China’s modernisation pathway, a pragmatic alternative to revolutionary egalitarianism, aimed at economic uplift without political liberalisation. Over time, Xiaokang was absorbed into the ideological architecture of the Chinese Communist Party, and under Xi Jinping it was elevated further, becoming the first “centenary goal” to be achieved by 2021. Crucially, Xi’s emphasis on rural revitalisation and frontier consolidation coincided with a new phase in China’s border strategy. It is in this context that the Xiaokang border villages must be understood.

Beginning in 2017, China launched the “Plan for the Construction of Well-off Villages in Border Areas of the Tibet Autonomous Region (2017–2020).” Under this initiative, more than 600 border villages were constructed or upgraded, supported by extensive road networks, communications infrastructure, and public services. These settlements span 21 border counties across Nyingchi, Shannan, Shigatse, and Ngari, regions that directly abut India, Bhutan, and Nepal. On the surface, the programme presents itself as poverty alleviation and rural development. In strategic terms, however, it represents a deliberate fusion of ideology, demography, and security. The Xiaokang villages are not merely habitations; they are instruments of statecraft. By populating remote, contested, or sparsely inhabited border spaces with loyal and economically dependent civilians, China quietly converts geographic ambiguity into administered normalcy. Sovereignty is embedded not through overt military presence, but through the routines of daily life, schools, clinics, party offices, surveillance systems, and infrastructure that binds these settlements firmly to the Chinese state. The frontier, in effect, is transformed from a military boundary into a lived political space.

Xiaokang provides the ideological glue that makes this transformation possible. Border residents are not treated as passive recipients of development, but as participants in national defence. The narrative of prosperity is inseparable from patriotic obligation, encouraging civilians to view themselves as custodians of the border. Traditional notions of collective responsibility are blended with modern nationalism, producing a civilian buffer that complicates military response and diplomatic protest alike. In Tibet, this approach serves an additional purpose: assimilation. Economic uplift is tightly coupled with political loyalty, narrowing space for dissent while reinforcing Beijing’s control over a sensitive region. Development, in this formulation, is not neutral; it is securitised.

We believed that limited infrastructure along the LAC was a stabilising factor. This was a profound misreading of how China looked at the same situation. China started building relentlessly, roads, tracks, logistics nodes, well away from the glare of crisis. They were not preparing for a war tomorrow. They were preparing so that if that likelihood ever came, it would arrive on their terms

For India, the significance of the Xiaokang villages lies precisely in this quiet transformation. They do not announce intent, yet they alter reality. They are built not during crises, but during calm, when attention is diffused, and resistance muted. They represent China’s long game at its most sophisticated, using time, ideology, and civilian presence to reshape the character of the border without firing a shot. By civilianising contested spaces, China has changed the terms of engagement. What were once ambiguous tracts have become administered zones; what were once military questions are now entangled with civilian welfare, development narratives, and sovereignty claims. The villages simultaneously serve multiple functions: surveillance, logistics support, political signalling, and legal positioning. They raise the cost of military action by embedding civilians into the strategic landscape and complicate diplomacy by blurring the boundary between civilian life and state assertion.

India, by contrast, historically treated border habitation as incidental rather than strategic. Border populations were often neglected, under-supported, and weakly connected to national infrastructure. Where China integrated military, civilian, administrative, and legal elements into a single continuum, India tended to keep these domains separate. The contrast is instructive. China turned habitation into a strategy; India treated it as an afterthought. The result is a frontier that appears peaceful, developed, and civilian, but is, in reality, deeply militarised by design.

China integrated civilians into its long game, India treated them as peripheral to it. The difference is telling. China layered its strategy, military, civilian, administrative, and legal, into a single continuum. India kept these domains largely separate.

Confidence-Building Measures: Ceiling Versus Floor

India’s embrace of confidence-building measures (CBMs) reflected its belief in stability as a shared good. Agreements in 1993, 1996, 2005, and 2013 were intended to freeze the status quo, prevent miscalculation, and buy time for economic growth and national consolidation. India treated these agreements as ceilings on behaviour. China signed the same agreements, but treated them as floors. The absence of a clearly demarcated boundary, combined with restrictions on force levels and weapon use, created precisely the conditions needed for grey-zone operations. Patrol confrontations, incremental encroachments, and forward posturing could all occur below the threshold of formal violation. India expected CBMs to constrain behaviour. China used them to define the outer limits within which pressure could be applied safely. These were not treaty violations; they were treaty exploitation.

Doklam: Reactive Assertion Against Incremental Pressure

The Doklam crisis of 2017 provides a sharp illustration of these divergent long games. China’s attempt to alter the status quo near the India–Bhutan–China trijunction was not impulsive. It followed years of diplomatic pressure on Bhutan, infrastructure development in the Chumbi Valley, and calibrated signalling. India’s intervention was decisive, justified, and strategically necessary. But it was also reactive. China’s long game had already unfolded across years of preparation. India’s long game asserted itself only when a clear red line was crossed. Doklam showed that India could act firmly, but also revealed that we were often responding to moves that had already set in motion.

The most refined expression of China’s long game along the LAC lies in the creation of Xiaokang border defence villages. They were conceived and constructed during periods of relative calm, and represent long game using time, ideology, and civilian presence to reshape the character of the border without firing a shot

Eastern Ladakh: Readiness Versus Resilience

The events of 2020 in Eastern Ladakh brought this asymmetry into stark relief. China’s actions that involved forward deployment, rapid mobilisation, permanent structures, logistics stocking, and rotational depth were not the result of any local initiative used by the local commanders. These moves reflected years of infrastructural, doctrinal, and organisational preparation. This was readiness produced by a long game. India’s response was courageous, resolute, and ultimately stabilising. But it required emergency mobilisation, rapid adaptation, and significant political will. India’s long game here demanded resilience under pressure rather than any pre-positioned advantage.

Both sides showed resolve. China entered the crisis already shaped by time. My experience at Rezang La helped me understand this not as a failure of will, but as a difference in strategic grammar. We believed that peace, once maintained, would endure. China believed peace had to be structured to advantage, or periodically revised. What we saw then was the harvest of time, time invested in infrastructure, doctrine, logistics, and political preparation. We responded with courage and resolve, but were responding to a situation that had been shaped long before the first tents appeared.

Diplomatic Time: Sectoral Leverage Versus Comprehensive Settlement

Even in diplomacy, the divergence persists. China has consistently pursued a sector-by-sector approach, settling where advantageous, deferring where leverage remains incomplete. India has sought comprehensive settlements that assume eventual convergence and mutual restraint. China assumes divergence and plans accordingly. India assumed convergence and prepared selectively. This difference matters because it determines how time is spent. China uses time to lock in gains incrementally. India uses time to defer resolution in the hope of balance.

Time does not reward patience alone. It rewards those who know how to use it. At Rezang La in 2009, I did not yet have the words for this realisation. Today, I understand that India and China were never playing the same long game. Both believed time was on their side. Only one treated it as a weapon

The Strategic Lesson: Time Is Not Neutral

The central lesson of the India–China experience is not that India lacked foresight, or that China was uniquely patient. It is that the two sides attributed different meanings to time itself. India believed stability would sustain itself. China believed stability had to be constructed, defended, and periodically tested. India’s long game was about becoming stronger while preserving peace. China’s long game was about reshaping the environment so that peace, when it existed, favoured China structurally, spatially, and psychologically. Both played long games. Only one treated time as a weapon. For diplomats and soldiers alike, this distinction is critical. Time does not reward patience alone. It rewards those who know how to use it deliberately, cumulatively, and without illusion. That perhaps is the most enduring lesson of this long and unfinished contest along the Himalayas.

A Soldier’s Observation

This article is not an indictment, nor a lament. India’s approach was and continues to be shaped by its values, its priorities, and its historical moments. As a soldier who has sat across the table, measured silence, and watched time work differently on each side, I believe one lesson stands out. Time does not reward patience alone. It rewards those who know how to use it. At Rezang La in 2009, I did not yet have the words for this realisation. Today, with the clarity that distance provides, I understand that India and China were never playing the same long game. Both believed time was on their side. Only one treated it as a weapon. That is a truth worth remembering, quietly, soberly, and without illusion, as we think about the future of the Line of Actual Control and our continued deployment along the Line of Actual Control.

The writer is a former senior Indian Army commander with extensive operational experience across high-altitude, counter-insurgency, and sub-conventional warfare environments. Over a distinguished career, he has translated battlefield command into strategic thought, contributing to doctrine, national security discourse, and professional military education. Post-service, he remains an influential strategic analyst and author, bridging operational experience with policy, geopolitics, and regional security studies