The Great Nicobar Project near the Malacca Strait, formally called the Holistic Development of Great Nicobar Island, was approved by the Indian government in 2021. The proposal to develop Great Nicobar was first floated in the 1970s, and its importance for national security and consolidation of the Indian Ocean Region has been repeatedly underlined. Increasing Chinese assertion in the Bay of Bengal and the Indo-Pacific has added great urgency to this imperative in recent years. The approval was not without hiccups though, as the project, with potential to become a strategic connectivity hub, was criticised for endangering indigenous rights, biodiversity, and legal safeguards. The extent of the project, which spans over 166 sq km, is about 10% of Great Nicobar’s 910 sq km area, including 84 sq km of denotified parts of a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve and Shompen and Nicobarese tribal reserves.

The Andaman and Nicobar Islands are a cluster of about 836 islands in the eastern Bay of Bengal. The two groups are separated by the 150-km-wide Ten Degree Channel. The Andaman Islands lie to the north of the channel, and the Nicobar Islands to the south. The Nicobar Islands, also known as Patai Takaru (Big island) by the locals, are situated in the southeast of the Bay of Bengal with 22 large and small islands. Among them, only 12 are inhabited.

Great Nicobar Island is the largest among the main islands in the Nicobar Islands, with Campbell Bay and Indira Point being the known tourist places. Indira Point, originally called Pygmalion Point, but renamed after the former prime minister who visited that place in 1984, is the southernmost point of India. With two national parks and a biosphere reserve, the Great Nicobar Island has tropical wet evergreen forests, mountain ranges reaching almost 650 m above sea level, and coastal plains. One in three bird species and one in four plant species of Great Nicobar are found nowhere else in the world. About 1200 km from India’s southern tip, about 210 km from Indonesia’s Aceh province, and roughly 900 km from the Malacca Strait, New Delhi is betting big on the Great Nicobar Project.

From the 17th century onwards, Portuguese and French missionaries tried to propagate Christianity in the Nicobar Islands. In 1756, Denmark took possession of these islands, but it abandoned them in 1848. The Andaman and Nicobar Islands only became a part of India after the British left the subcontinent in 1947, formally having previously taken possession of the islands in the late 18th century in 1869.

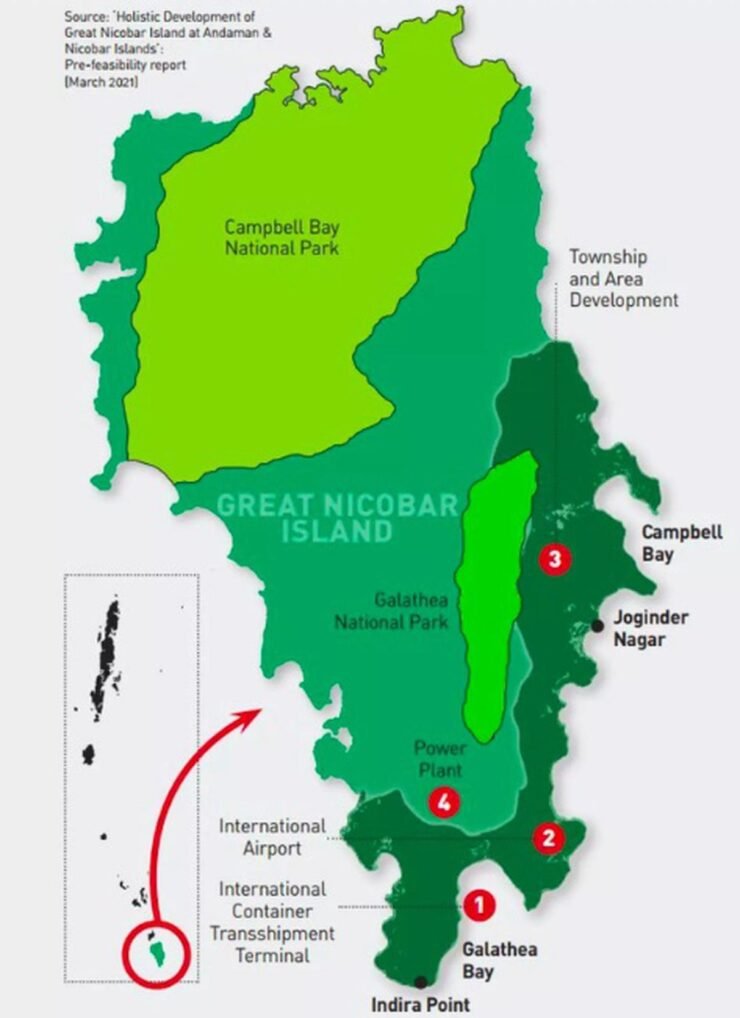

Planned across 166 sq km, it is an ambitious greenfield city project worth Rs 72,000 crore, with an integrated development plan comprising an international container transhipment terminal, a greenfield international airport with a 3,300-metre runway, a 450 MVA gas- and solar-based power plant, and a township covering 16,610 hectares

During World War II, Japan occupied the islands and temporarily placed them under the Azad Hind government led by Subhas Chandra Bose, who renamed them Shaheed Dweep and Swaraj Dweep. However, the British reasserted control, and after their departure, the islands were absorbed into the newly independent India.

The Andaman and Nicobar Islands became part of India during the decolonisation process after World War II, after the British transferred their directly administered territories. Britain had acquired control of the islands from Denmark and integrated them into British India, and following the partition of British India into India and Pakistan, the islands were transferred to India along with other directly ruled territories.

Mega-infrastructure project

The Great Nicobar Island Development Project (GNIP) is a planned mega-infrastructure project for the southern tip of India’s Great Nicobar Island, in the Andaman Sea. The island comes under the Nicobar district administration in the Indian union territory of Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Launched in 2021, GNIP was conceived by Niti Aayog. Experts say the port, offering a natural deep-water harbour with minimal dredging needs, positions India as a gateway to Southeast Asia.

The Great Nicobar Island Development Project (GNIP) is a planned mega-infrastructure project for the southern tip of India’s Great Nicobar Island, in the Andaman Sea. The island comes under the Nicobar district administration in the Indian union territory of Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Launched in 2021, GNIP was conceived by Niti Aayog. Experts say the port, offering a natural deep-water harbour with minimal dredging needs, positions India as a gateway to Southeast Asia.

Planned across 166 sq km, it is an ambitious greenfield city project worth Rs 72,000 crore (Rs 81,000 crores revised estimates) with an integrated development plan that comprises an international container transhipment terminal (ICTT) at Galathea Bay with a capacity of 14.2 million TEU (Twenty-Foot Equivalent Unit), a greenfield international new airport with a 3,300-metre runway, a 450 MVA gas and solar-based power plant and a township of an area of 16,610 hectares. The expansion will include the addition of a cruise terminal, a shipbreaking yard, and a coastal transport corridor, later. The Andaman and Nicobar Islands Integrated Development Corporation (ANIIDCO) is responsible for its implementation.

The first phase of the Great Nicobar Island project, which includes the International Container Transhipment Port (ICTP), is on track to go operational by 2029. The overall project will be completed in three phases, with development spanning approximately 30 years; its total duration has not yet been fully defined beyond this initial operational date. The port aims to rival Singapore’s transhipment through the China-influenced Malacca Strait, a lane carrying roughly 25% of global trade. This could capture regional transhipment, reducing India’s logistics dependence.

The greenfield dual-use airport will be capable of handling wide-body aircraft, managing 4,000 passengers per hour at its peak and enhancing civilian access and defence deployment. The airport will further offer a forward base for surveillance and logistics in the Indian Ocean region. The port will be controlled by the Indian Navy, while the airport will have dual military-civilian functions and will cater to tourism as well. The new township will grow from 8,000 to over 3 lakh people eventually and include industrial zones and residential areas, with a significant chunk of the rainforest being effectively urbanised. The gas and solar power plant by itself will power the massive infrastructure, ensuring energy self-sufficiency.

Geostrategic position

Great Nicobar Island’s geostrategic position makes it critically important for India’s security and maritime influence and will prove to be an asset for India’s naval capabilities, power projection, strategic calculus and operations in the Indo-Pacific. It is located at the mouth of the Malacca Strait, one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes, accounting for the passage of one-third of global sea trade. The island is also close to the Sunda Strait, the Lombok Strait, and the Coco Islands, all of which are important choke-points in the Indo-Pacific region where India is wary of a build-up of Chinese maritime forces. China’s attempt to expand its footprint in the region includes building a military facility at Coco Islands (Myanmar), lying just 55 km to the north of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

The island could serve as India’s frontline in the eastern Indo-Pacific against potential maritime threats. Close surveillance of the entire area around the archipelago and the building up of a strong military deterrence at Great Nicobar will be of vital importance to India’s national security. The project will bolster the existing tri-services military command in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands and will allow India to station ships, aircraft and drones closer to the strategic crossroads of the eastern Indian Ocean to monitor critical sea lanes and further enhance India’s security sphere in the region. Real-time monitoring and interdiction of the naval assets of China and other nations entering the Indian Ocean will become a reality.

The geostrategic position of Great Nicobar Island makes it critically important for India’s security and maritime influence as it is an asset for naval capabilities, power projection, strategic calculus and operations in the Indo-Pacific. It is located at the mouth of the Malacca Strait, one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes, accounting for one-third of global sea trade

The island is positioned close to the East-West international shipping corridor, through which a very large part of the world’s shipping trade passes. Economically, the port could generate Rs 30,000 crore in annual revenue by 2040, according to government estimates, while creating 50,000 jobs. It aligns with the Centre’s Sagarmala initiative, which promotes development in coastal economic zones. India is seeking to harness the commercial transhipment potential in its southeastern fringe, leveraging key shipping lanes while countering China’s ‘string of pearls’ in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR).

The island’s proximity to the Malacca Strait, through which 80% of China’s oil imports pass, makes it a vantage point for India and global maritime traffic. The project draws inspiration from global models like Singapore and Hong Kong, and aims to transform the island into a ‘growth pole’ for the BIMSTEC region. It seeks to strengthen India’s maritime presence and control near the busy Malacca Strait and aims to establish India as a major player in global shipping, reducing reliance on foreign ports like Singapore and Colombo. It is designed to compete with major transhipment hubs like Singapore and provide a strategic location for Indian trade. It will substantially reduce the dependency of the current 75% of India’s transhipment cargo handled by ports outside the country, and besides handling our cargo, also offer the services to the international market at a cost. The transhipment port will accrue significant benefits such as forex savings, foreign direct investment, increased economic activity at other Indian Ports and enhanced logistics infrastructure.

As the region is ecologically important and fragile, the project has alarmed many environmentalists. Controversies over tribal rights and ecological concerns cropped up from the beginning. The project threatens nearly 130 sq km of pristine tropical forests, raising legal and ethical concerns

Biodiversity hotspot

However, the proposed massive infrastructure development in an ecologically important and fragile region has alarmed many environmentalists. Controversies over tribal rights and ecological concerns have cropped up from day one of the project. The project threatens nearly 130 sq km of pristine tropical forests, part of the Andaman and Nicobar biodiversity hotspot, raising legal and ethical concerns over how India balances development and ecological preservation. It has sparked procedural, ecological and displacement concerns, and is facing scrutiny, even as some environmental clearances have been granted for some phases after assessments and public hearings, though further approvals are pending. The rapidity and haste with which the terms of reference for the environmental impact assessment (EIA) were finalised, disregarding due diligence, are under the scanner.

The Great Nicobar Island is one of the most pristine and isolated ecosystems on the planet, with a unique wildlife. As per the Government, the project poses no threat to the island’s tribal groups, does not come in the way of any species, and does not jeopardise the eco-sensitivity of the region. The same is, however, being contested by environmentalists. An estimated 237 Shompen and 1,094 Nicobarese individuals now live in a 751 sq km tribal reserve, some 84 sq km of which is proposed to be de-notified. The Shompen are hunter-gatherers who depend on forest and marine resources for sustenance. The Nicobarese, who lived along the west coast of the island, were mostly relocated after the 2004 tsunami.

The project poses a threat to the indigenous Nicobarese and Shompen communities, with concerns about land acquisition, displacement, and the loss of cultural heritage. There are fears about the project’s potential to disrupt traditional livelihoods and introduce diseases to isolated communities. The critics highlight the potential harm to the island’s rich biodiversity, including the nesting grounds of the world’s largest leatherback sea turtles at Galathea Bay, which is a Ramsar wetland, and thousands of Coral colonies and seagrass meadows. The dredging of millions of cubic metres of seabed could destroy the coral reefs and seagrass meadows, and disturb the turtles’ nesting beaches. Development will also undermine natural coastal defences, as the mangrove belts at Galathea that help buffer tsunamis and storms would be removed. The island lies in a seismically active zone, and large-scale reclamation may worsen erosion and seismic risks. They sit atop the same megathrust fault line that triggered the devastating Indian Ocean tsunami in December 2004.

Besides this, the Great Nicobar Island is home to unique flora, endemic orchids, and ferns, alongside mangroves in Galathea Bay. An estimated 9.64 lakh trees will be required to be cut, officially, but independent estimates put the figure many times higher, as the forests there are very densely packed with the Nicobar megapode and the Nicobar tree shrew. It will also negatively impact the carbon sequestration capacity of the region. The proposal of compensating for the deforestation by planting an equal number of trees in the Aravallis in Haryana is also most unrealistic and unreasonable. Critics argue that the loss will be complete, irreversible, and irreplaceable for the forests that are destroyed for the project on Great Nicobar.

A way forward may lie in adopting a community-inclusive model of development in a phased and ecologically sensitive manner. The task of safeguarding biodiversity and cultural heritage while ensuring national interests are met will be challenging. But India’s security concerns must take precedence over other issues

The loss of tree cover will not only affect the flora and fauna on the island, but it will also lead to increased runoff and sediment deposits in the ocean, impacting the coral reefs in the area. The ecological fragility, tribal rights, and disaster vulnerabilities of the island must be addressed. Transparency in the declassification of the report by the high-powered committee consisting of environmental and tribal experts formed by the National Green Tribunal (NGT) may be in order.

Way forward

All said and done, by integrating maritime, transport, and economic infrastructure, the project has the potential to strengthen connectivity, trade, and defence and contribute to India’s long-term strategic vision for the islands as a hub for security, trade, and regional influence. The project is set to transform the region, dragging it into a world of untapped economic opportunity.

Finally, a way forward may lie in adopting a community-inclusive model of development in a phased and ecologically sensitive manner. The task of safeguarding biodiversity and cultural heritage while ensuring national interests are met will be challenging. India’s security concerns must, however, take precedence over all other issues, as the rapidly transforming global order has the potential to derail India’s rapid progress across all spheres. The prosperity and existence of the country must not be put at risk, and we should crystal gaze far into the future and prepare to defend ourselves from any eventuality.

The writer is an armed forces veteran who has been an instructor at OTA, Chennai and Army War College, Mhow. He has commanded an Infantry Battalion Group with UN in Sudan and an Infantry Brigade in the Northern Sector