With Israel in the process of expanding ground operations in Gaza, Tel Aviv’s aerial bombardment has allegedly destroyed 150 underground targets and eliminated the chief of Hamas’ aerial operations. This, despite Iran’s repeated warnings to Israel of grave results if Tel Aviv does not cease its unrelenting aerial assault of the Gaza Strip. This article analyses Tehran’s appetite and capacity for conflict with Israel, and consequently the threat to Israel from a possible Iranian intervention.

Iran’s Willingness to Intervene

Iran had earlier threatened to intervene in the conflict if Israel launched a ground operation in the Gaza Strip. Even the US was not dismissive of Tehran’s threat, with US National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan claiming that the US “cannot rule out that Iran will decide to intervene directly.” On the other hand, the Islamic Republic’s supreme leader Ayatollah Khamenei had rubbished speculation that Iran had assisted Hamas in planning its October 7 attack on Israel. However, with Tel Aviv having paid no heed to Iran’s threats, Tehran is yet to follow through on its bluster.

Iran’s warnings are sometimes viewed as a statement of intent for Tehran to enter the conflict through its support groups and proxies. The Hezbollah militant outfit, which is already involved in low-intensity skirmishes across the Israel-Lebanon border, and President Bashar al-Assad’s government in Syria are both closely oriented toward Tehran. At least in theory, therefore, Iran’s entry into the Gaza war would mark a new phase in Israel-Iran hostilities and possibly expand the arena of fighting into Iranian territory. Thus, Tehran’s reluctance to directly enter the war appears premised on the fear of a damaging Israeli retaliation.

Iran has admitted that its recent agreement with the United States on the release of prisoners and de-freezing of Iranian financial assets may be a precursor to negotiations on other issues including its nuclear programme – a deal which could convince the US and its allies to lift sanctions on Iran’s crude oil exports, increasing global supply

Tehran’s intervention in the conflict would also constitute a bullish development for international crude oil prices, but not to Iran’s benefit. It would be major OPEC+ exporters like Saudi Arabia and Russia, on the other hand, that would emerge as the principal beneficiaries of increasing oil prices. After all, Washington could be expected to punish Tehran for such an escalation by not turning a blind eye anymore to Iranian crude oil exports despite sanctions against the same.

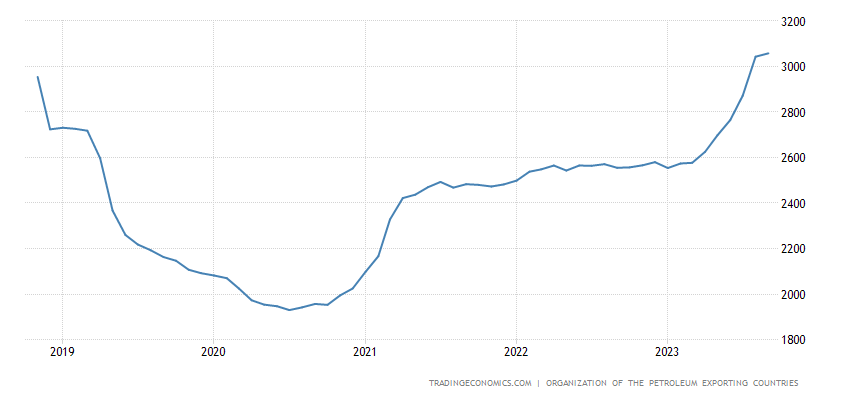

Further, Tehran has itself admitted that the recent agreement with the US on the release of prisoners and de-freezing of Iranian financial assets may be a precursor to negotiations on other issues including its nuclear programme – a deal which could convince the US and its allies to lift sanctions on Iran’s crude oil exports, increasing global supply. Significantly, Iran has already expanded its crude oil output to its highest level since 2018 (see Figure 1).

It is hence apparent that Iranian authorities are completely aware that a conflict with Israel could prove extremely costly for the Islamic Republic. In addition to Israeli military retaliation on Iranian defence installations, political consequences could follow for a repressive regime increasingly unpopular among Iran’s citizenry.

Iran’s Capacity to Intervene

Despite the above considerations, if Tehran is willing to enter the conflict actively, it has multiple choices at its disposal. These include continuing what it has been engaging in for years – channelling funds and weaponry to Iran’s proxies in the region, such as Hezbollah. It could also force or incentivise other nations to support its efforts against Israel. Finally, it could hypothetically try to attack Israel on its own, despite not sharing a common geographical border with the country.

If Tehran decides to send aircraft and missiles toward Israel, Iraq may simply ignore the overflight of its airspace given Baghdad exercises very limited control over its airspace. Further, Syrian airspace would need to be crossed to reach Israel, though this should not pose a major impediment since Damascus is sympathetically disposed toward Iran. Conversely, traversing Jordanian airspace unchallenged would be problematic given its favourable disposition toward Israel.

While the West may be unable to intercept all ballistic missiles targeted by Tehran against Israel, it could certainly try to intercept attacking Iranian aircraft, even before they are able to ingress the well-defended Israeli airspace. Operating almost 600 aircraft including over 250 attack aircraft, well-supported by early warning systems and backed up by a reasonably potent air defence network, the Israeli Air Force is well-positioned to secure the country’s compact airspace against incursions by Iranian aircraft. It is therefore likely that whatever planes Tehran could muster to fly such a long distance, would be unable to accomplish any meaningful objective, and would suffer high losses. Iran’s air force does operate a couple of tanker aircraft which could enable a few dozen fighter jets to cover the distance, but other aircraft would hardly be effective.

Whatever number of aircraft Tehran could muster to fly such a long distance would be unable to accomplish any meaningful objective, and would suffer high losses. Iran’s air force does operate a couple of tanker aircraft which could enable a few dozen fighter jets to cover the distance, but other aircraft would hardly be effective

Bomb delivery utilising standoff armaments such as air-launched cruise missiles (ALCMs) would be a safer option for Tehran, but Iran is unlikely to possess an extensive stockpile of cruise missiles – particularly compact air-launched ones. Because of problems in acquiring miniaturised jet engine technology, Iran has not been able to induct many such systems. For perspective, even the United Kingdom possesses no more than 1,000 such munitions, while Iran would have to deploy hundreds of such missiles to launch an effective attack on Israel.

Iran could also use larger ground-launched cruise missiles, which it has been operating for about a decade. However, it is once again likely that only limited numbers of sufficiently long-range variants are available. In practice, even these limited numbers would likely be curtailed by the limited approach vector through Syria, enabling early detection and neutralisation by Israel’s well-networked air defences.

Iran’s ballistic missiles could prove more potent, particularly the ones which fly to a higher altitude at faster speeds. The shorter-range, slower missiles could be mostly intercepted by air defence systems like Israel’s Patriot, but do not matter in any case precisely because of their limited reach (see Figure 2). Iran’s ballistic missile arsenal includes a variety of variants and sub-variants, many of which were only developmental models, and several others lacking the range required to reach Israel.

In March 2022, the commander of the US Central Command General McKenzie said that Iran possessed approximately 3,000 ballistic missiles, some of which could strike the Israeli city of Tel Aviv. Even if it were assumed, optimistically for Iran, that half of these could reach Israel, many of the missiles would be older variants – essentially oversized scud types. The liquid-propelled Shahab-3 and its subsequent iterations like the Emad and Ghadr could constitute potent threats despite their limited manoeuvrability, given their accuracy and high flight speeds (see Figure 3). On the other hand, it is likely that such modern missiles constitute a very small fraction of Iran’s inventory, nowhere close to half of its ballistic missiles. With a few hundred such warheads, Tehran could at best hope to terrorise Israel’s general population and damage a few large military targets like air bases, but hardly dent the Israeli state’s overall military capacity.

A greater impact could be achieved if Iran is able to smuggle lots of suicide drones closer to Israeli territory, and launch them every day in large numbers – say from Syria or Lebanon. There are many such Iranian unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), ranging from the large and weighty Shahed-131 to the diminutive Meraj-532 drones, comparable to the US’s Switchblade munitions (see Figure 4). If Tel Aviv felt compelled to launch even limited invasions of Lebanon or Syria to find and neutralise the drone launchers, it would be more harmful for than any real destruction such drones could accomplish on Israeli territory, simply because of the expansion of the war to new fronts and the consequent demands on Israel’s defensive resources.

Outlook

Tehran’s threats of attacking Israel could be mere posturing. The leadership of its proxy, Hezbollah, has maintained a low profile with spokeswoman Rana Sahili clarifying that the increase in skirmishes with Israel does not imply that Hezbollah had chosen to fully enter the Hamas-Israel war, but only constitutes a “warning” to Tel Aviv. Hence, it is not guaranteed that Iranian pressure, if applied, would succeed in pushing Hezbollah into the war. But if Tehran could manage to accomplish this, then this would constitute a much greater threat to Israel than all the afore-discussed drone and missile strikes. Hezbollah claimed to have one lakh fighters in 2021, but the Institute for National Security Studies (INSS) – an Israeli think tank – estimated it at half that number. The group is also better trained, more experienced, and better equipped than Hamas.

While Hezbollah lacks sophisticated systems like tanks and air defences, they possess several contemporary anti-tank munitions, man-portable air defence systems (MANPADS), and approximately 1,50,000 rockets and missile systems – most with a range of a few dozen kilometers (see Figure 5). Their sheer numbers would make it challenging for even Israel’s integrated air defences to intercept all.

Given the above, Tehran’s best option to hurt Israel appears to be by using its proxies, particularly Hezbollah. Notably, on October 19 the US Navy claimed to have intercepted three land-attack cruise missiles and several drones launched by Yemen’s Iran-backed Houthi rebels, possibly targeting Israel. The Houthis have since pledged to continue attacking Israel if it does not cease its operations in Gaza.

Tehran’s threats of attacking Israel could be mere posturing. The leadership of its proxy, Hezbollah, has maintained a low profile with spokeswoman Rana Sahili clarifying that the increase in skirmishes with Israel does not imply that Hezbollah had chosen to fully enter the Hamas-Israel war but only constitutes a warning to Tel Aviv

However, in the unlikely scenario that such proxy interventions impinge on Tel Aviv’s ability to sustain operations in the Gaza Strip, they might prompt an outright military retaliation against Iran. In fact, Israel has purportedly carried out no less than two dozen operations including assassinations, drone strikes, and cyberattacks against Iran since 2010, with most targets linked to the Islamic Republic’s contentious nuclear programme, which Israel views as an existential danger. Moreover, two facilities that were part of Iran’s drone programme were targeted by drones last year. Hence, Tehran would be cognizant of the significant cost associated with any involvement in the Gaza War which Tel Aviv views as having the potential to alter the tactical balance in favour of Hamas, thereby rendering the likelihood of such an intervention quite low.

-The writer is serving as a Fellow at Observer Research Foundation. The views expressed are personal and do not necessarily reflect the views of Raksha Anirveda

The writer is an independent researcher with publications spanning diverse fields, including terrorism and counter-terrorism, foreign policy, climate finance, microfinance, maritime security, corporate finance, and industrial organisation.