It is hard to fathom the ongoing delay in FICV (Future Infantry Combat Vehicle) project. Despite having spent almost a decade on planning the blueprint, the project has not taken off yet and deliberations are still on to arrive at a roadmap that is well planned, acceptable and executable with time-line urgency roadmap. The fate of FICV project still hangs in uncertainty – will it move forward and come to its logical end or will final curtains be put on it under the safe cover of quick fix import solution.

Why this stalemate? As a keen observer on the other side of the fence, it has been taking a heavy toll on my thought process and hopefully the same may be the case with others as well. Can India as a nation that has been striving hard to strengthen its strategic autonomy and establish itself as a key player in the global new order, be at leisure with a laid back attitude? No, would be the unanimous response. A nation’s strategic autonomy can’t be achieved until and unless it achieves the goal of self-reliance in its defence capability along with an effective military deterrence build-up. After all, these two are the most critical aspect that forms the core of strategic autonomy.

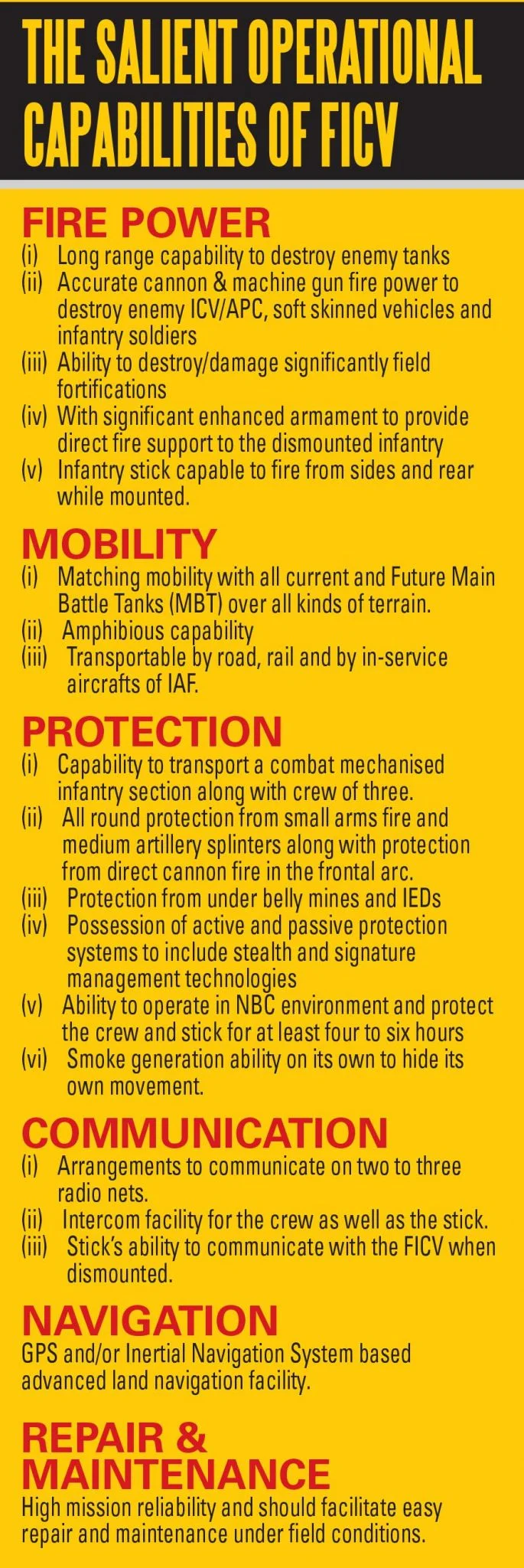

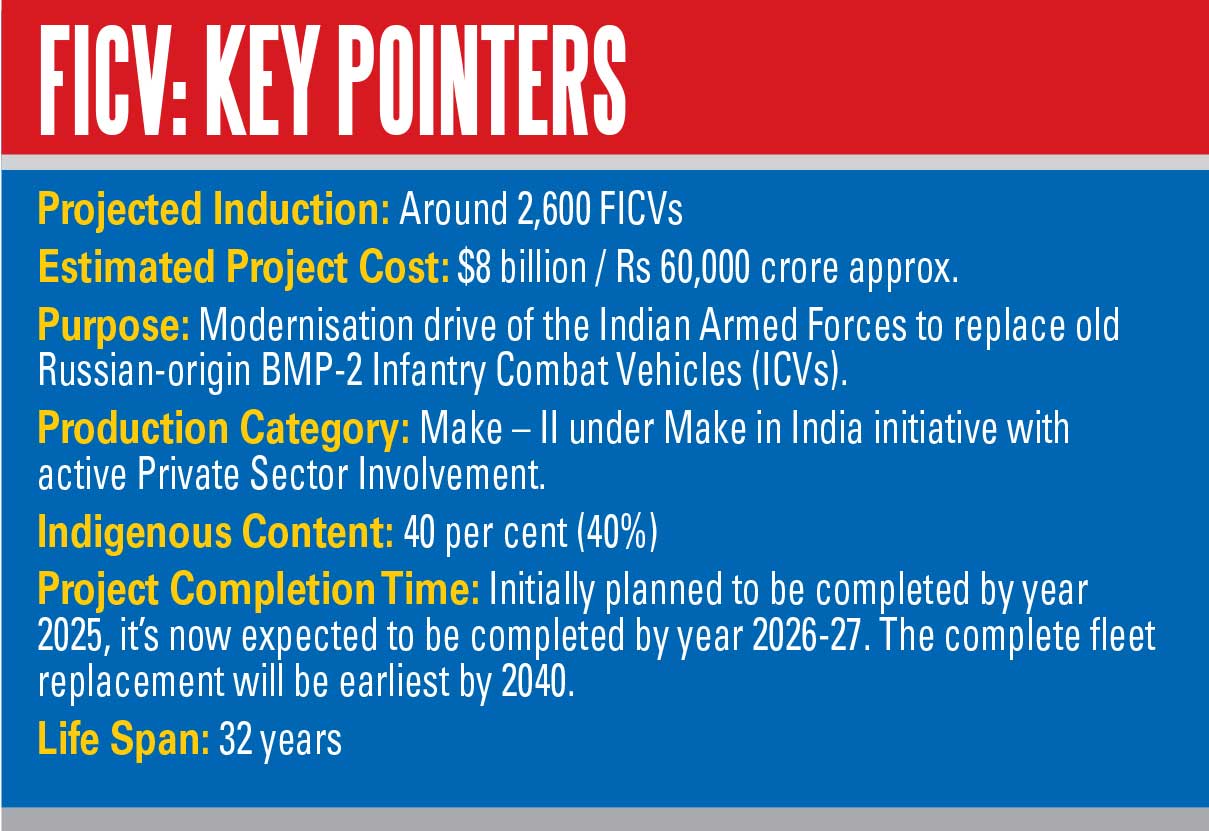

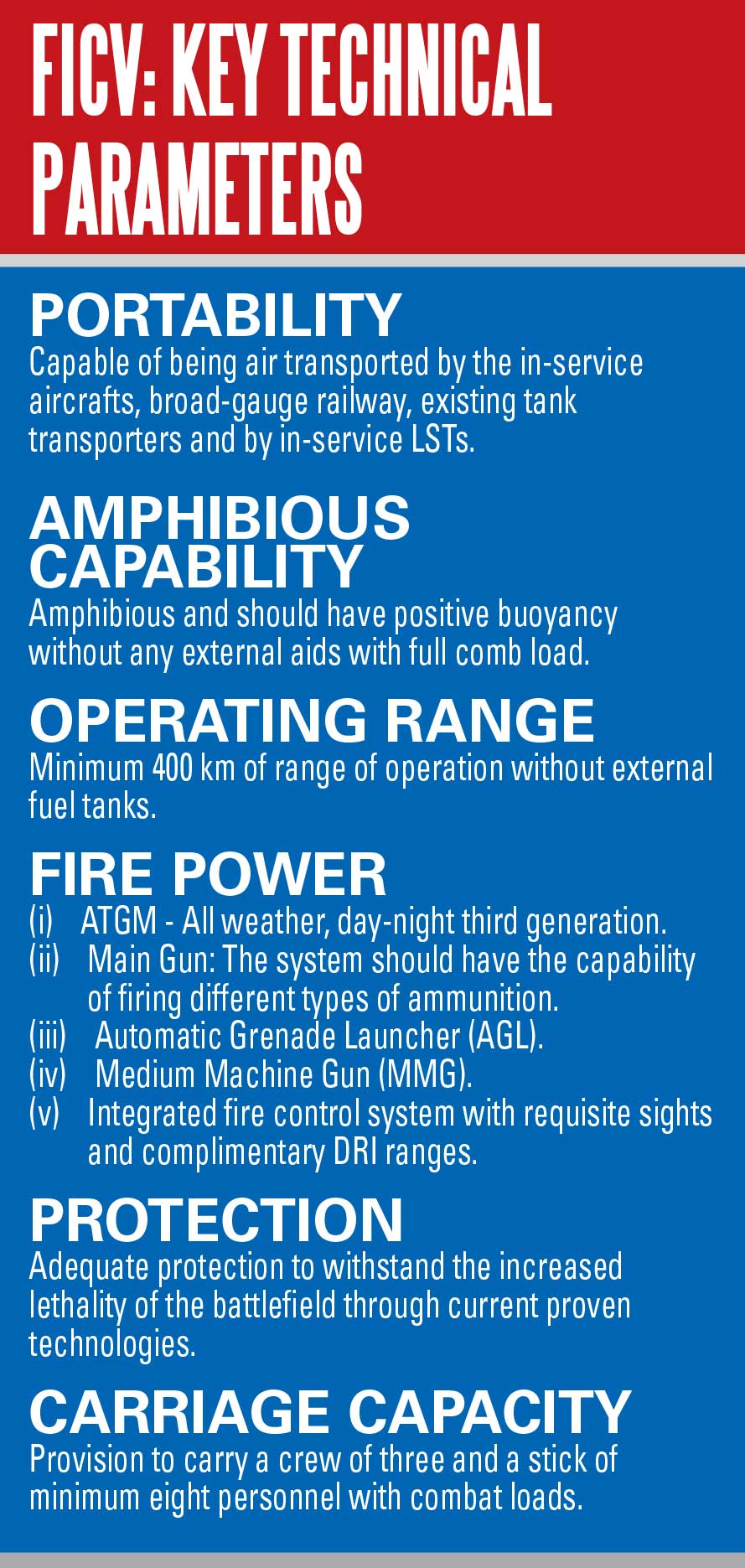

The project originally was to be executed as a ‘Make’ project under the Defence Procurement Policy 2008 involving indigenous design, development and production for procuring the Future Infantry Combat Vehicle. Conceived as a system-of-system project, the focus was to have FICVs with advanced technical features and operational capabilities, embedded with challenging technologies and lethal weapon systems. The box items provide a glimpse of the key operational and technical parameters:

Later, after being tossed up for years as tennis ball from one end to other and getting smashed/ hit as a shuttle cock, project FICV finally landed into the Make-II category with an assumption that henceforth, the project will be fast-tracked and further speed up the modernisation of the armoured vehicles of the Indian Army. Additionally, it will also bring in the energetic involvement of the private sector in the defence sector and Make in India initiative. Under Make -II, there will be no government funding for prototype development purposes, but there will be assurance of orders on successful development and trials of the prototype. It was a major shift to focus on development of equipment/system/platform or their upgrades or their subsystems/sub-assembly/assemblies/components.

This shift of category change from Make to Make-II highlighted the major differences of opinion between the end user (Indian Army) and the Ministry of Defence (MoD). Moreover, in the absence of clarity and lack of any commitment from the end user regarding its requirement of the vehicles, the industry too has been reluctant to participate in the project. The wait and watch game continues.

This shift of category change from Make to Make-II highlighted the major differences of opinion between the end user (Indian Army) and the Ministry of Defence (MoD). Moreover, in the absence of clarity and lack of any commitment from the end user regarding its requirement of the vehicles, the industry too has been reluctant to participate in the project. The wait and watch game continues.

At present, Indian companies that have sent in their proposals to MoD are Titagarh Wagons, Reliance Defence and Engineering and Mahindra and Mahindra. And in due course, subject to approval some of the potential Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) that include Russian companies under the umbrella of Rosoboronexport, US-based General Dynamics and German Rheinmetall among others will join the fray as strategic partners.

Thus, it becomes clear that project funding issue and indecisiveness to spell out the actual order requirement of the FICVs were the major factors among others that kept the project off the track till date. Though with Make–II, the initial funding issue has been resolved (till prototype development); clear numbers of the FICV requirements are still missing.

Thus, it becomes clear that project funding issue and indecisiveness to spell out the actual order requirement of the FICVs were the major factors among others that kept the project off the track till date. Though with Make–II, the initial funding issue has been resolved (till prototype development); clear numbers of the FICV requirements are still missing.

Taking the aforementioned into consideration, the chart below is an attempt to present a simplistic solution to break the complex FICV jinx. It is for the experts and people at the helm of affairs to decide its worthiness with their own interpretation.

As mentioned above selection of two winners at the design selection will make way for competitive playing field and will help in building a vibrant defence ecosystem in the long term. Bringing in academia and start-ups through a special design competition into the play would be a plus. Further, with declaration of the actual requirement number of FICVs at the design selection or prototype selection stage (after successful completion of trials) and proportionate distribution of the order to both participants, efficient execution of the order and timely delivery of the FICVs will be fully secured. The incentive provision will help overcome the existing trust deficit and enhance the confidence level of the industry to take up the future challenge.

When the incumbent government starts a new inning, the task will be cut out for it to foresee an early manifestation of FICV through prioritised, responsible, responsive decision making and adequate funding. It will have to blend its policies with twin objectives – national prosperity aligned with national security.

The new and strong India has chosen modernisation and it demands from government a sensible purpose that’s driven by right perspective. Therefore, in order to streamline defence procurement, capability building and re-energise the Indian defence ecosystem – the future economic policy will have to take defence (national security) into its ambit along with the current socio-economic-welfare objective. Doing so may require lots of hat rollover, change in perspective, mindset alterations and inclusive cooperation for initiating the sprint run into the future.

The new and strong India has chosen modernisation and it demands from government a sensible purpose that’s driven by right perspective. Therefore, in order to streamline defence procurement, capability building and re-energise the Indian defence ecosystem – the future economic policy will have to take defence (national security) into its ambit along with the current socio-economic-welfare objective. Doing so may require lots of hat rollover, change in perspective, mindset alterations and inclusive cooperation for initiating the sprint run into the future.

The massive mandate and faith imposed in the incumbent government for another full term, instils a reasonable optimism that massive reforms/ changes, some being radical ones are on the anvil to be unleashed by the determined government/ executives sooner than later. Hopefully, the FICV jinx too will be broken and achieve its realistic optimisation.