The Galwan Valley clash of June 15, 2020, represents the most serious military confrontation between India and China since the 1967 incidents at Nathu La and Cho La. The deaths of 20 Indian soldiers and an undisclosed number of Chinese troops shattered the long-held assumption that confidence-building mechanisms could indefinitely prevent fatalities along the LAC.

For nearly three decades, New Delhi and Beijing managed their unresolved boundary dispute through diplomatic engagement, military protocols, and restraint in the use of force. Galwan exposed the limits of this framework. It marked the end of what may be termed ‘managed tranquillity’ and the beginning of a phase characterised by sustained forward deployments, hardened military postures, and diminished political trust.

The Structural Origins of the Crisis

Ambiguity of the Line of Actual Control. The LAC is not a mutually delineated boundary but a product of competing historical narratives and cartographic interpretations. In eastern Ladakh, overlapping perceptions of the LAC create multiple friction points where patrols frequently intersect. While ambiguity previously allowed flexibility and de-escalation, it also created opportunities for coercive revisionism.

China’s Evolving Border Strategy. Since 2013, China has demonstrated a growing willingness to assert its claims through forward deployments and tactical pressure. Incidents at Depsang (2013), Chumar (2014), and Doklam (2017) reflected a pattern of probing and consolidation rather than isolated tactical disagreements. Under Xi Jinping, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has undergone significant reorganisation, emphasising jointness, rapid mobilisation, and readiness for “local wars under informationised conditions.” Border management has become an extension of this doctrine, blending military pressure with political signalling below the threshold of conventional war.

India’s Infrastructure Push. India’s accelerated border infrastructure development after 2016 altered the operational environment in Ladakh. Improved roads, bridges, and airfields reduced India’s historical logistical disadvantages. From a Chinese perspective, these developments challenged long-standing assumptions of superiority and threatened freedom of manoeuvre in areas such as the Depsang Plains.

Daulat Beg Oldie and the Strategic Geometry of Eastern Ladakh

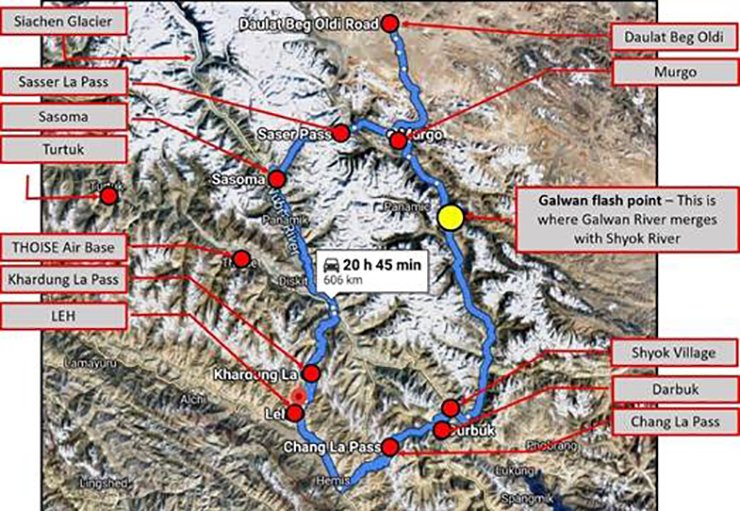

Geographical Significance. Daulat Beg Oldie (DBO), located at approximately 16,600 feet, is India’s northernmost military outpost and one of the highest operational Advanced Landing Grounds in the world. Situated near the Karakoram Pass, it occupies a critical position linking concerns related to China, Pakistan, and the Siachen sector.

The Depsang Plains. The Depsang Plains constitute one of the few areas along the LAC suitable for mechanised movement. Control over this sector carries operational significance disproportionate to its size. India’s access to Depsang is logistically anchored in DBO, making the latter indispensable for a sustained military presence in the sub-sector North. PLA efforts since 2013 to block Indian patrols in Depsang have been aimed at operational denial rather than outright territorial capture. These actions reflect Chinese sensitivity to India’s growing ability to contest space in an area previously assumed to be secure.

The DS–DBO Road. The completion of the Darbuk–Shyok–Daulat Beg Oldie Road fundamentally altered the balance in eastern Ladakh. By enabling rapid mobilisation and sustained logistics, the road transformed DBO from an isolated outpost into a viable operational hub. Chinese pressure in Galwan Valley must be understood in this context: Galwan lies astride the DS–DBO axis, and instability there directly threatens India’s logistical access to DBO.

The 2020 Standoff and the Galwan Clash

PLA Forward Deployments. In April-May 2020, the PLA undertook coordinated deployments across multiple friction points in eastern Ladakh, including Galwan, Pangong Tso, Hot Springs, and Depsang. The scale and simultaneity of these moves indicated centralised planning rather than local initiative.

Disengagement Talks and Breakdown. Military and diplomatic engagements produced limited disengagement agreements in early June. However, implementation on the ground proved inconsistent. On June 15, an Indian verification patrol encountered PLA troops who had not fully withdrawn from agreed positions in Galwan Valley.

The Clash. The ensuing confrontation escalated into violent hand-to-hand combat. Firearms were not used due to existing agreements, but improvised weapons and the extreme terrain resulted in fatalities. The clash marked the first combat deaths on the LAC in over four decades.

Galwan as Deliberate Coercion. Galwan was not an accident arising from miscalculation. Several factors indicate deliberate design: Pre-positioning of PLA reinforcements, use of non-firearm violence consistent with PLA escalation control and timing during disengagement verification. The episode fits within a broader Chinese approach of employing calibrated force to impose costs without triggering full-scale conflict.

India’s Response and Strategic Shift

Military Measures. India responded with large-scale deployments across eastern Ladakh, inducting armour, artillery, air defence systems, and combat aircraft. Extensive winter stocking and habitat construction demonstrated intent to maintain a sustained forward presence.

Political and Economic Signalling. Politically, India articulated a clear linkage between border stability and the overall bilateral relationship. Economically, measures restricting Chinese investments and digital platforms signalled a willingness to impose costs beyond the military domain.

Implications for Confidence-Building Measures

Galwan exposed the inadequacy of existing CBMs in the face of deliberate coercion. Protocols premised on mutual restraint proved ineffective against an adversary willing to exploit ambiguity. The episode necessitated a reassessment of rules of engagement and deterrence posture.

Key Lessons Learnt

The Galwan Valley clash was not merely a tactical episode but a strategic shock that exposed deep structural flaws in India-China border management and compelled a reassessment of long-held assumptions. The lessons derived from Galwan extend beyond eastern Ladakh and have enduring relevance for India’s military posture, diplomatic engagement, and strategic planning.

The Line of Actual Control Is a Live Military Frontier. Galwan conclusively demonstrated that the LAC can no longer be treated as a largely political boundary managed through patrolling protocols and episodic negotiations. It has become a contested and militarised operational theatre, where force postures, logistics, and readiness directly influence outcomes. The assumption that escalation could always be prevented through local commander-level engagement proved untenable when confronted with deliberate, centrally directed coercion. Stability on the LAC is now contingent on sustained force presence rather than procedural restraint. This necessitates long-term deployments, hardened infrastructure, and a shift from crisis response to permanent deterrence management.

Confidence-Building Measures Are Ineffective Without Deterrence. The existing CBM framework, particularly agreements restricting the use of firearms, was premised on mutual restraint and political trust. Galwan exposed the fragility of this premise. By exploiting these restrictions through the use of improvised weapons and numerical advantage, the PLA demonstrated how CBMs can be weaponised by a determined adversary. This does not argue for the abandonment of CBMs but underscores the need for deterrence-backed CBMs. Agreements must be underwritten by credible force postures, clear red lines, and revised rules of engagement that reduce asymmetry and restore tactical balance.

Infrastructure Development is a Strategic Stabiliser, not a Provocation. A persistent narrative, often echoed in Chinese discourse, is that Indian infrastructure development ‘provoked’ the 2020 crisis. Galwan disproved this claim. Infrastructure did not cause Chinese assertiveness; it revealed it. The DS–DBO road reduced India’s historical logistical vulnerabilities and enabled a sustained presence in the sub-sector North. Chinese efforts to obstruct Indian activity in Galwan and Depsang indicate that infrastructure parity threatens coercive leverage. The lesson is clear: infrastructure enhances deterrence by denying the adversary easy gains, even if it temporarily raises friction.

China Employs Calibrated, Below-Threshold Violence. Galwan illustrated a distinct Chinese operational approach: the deliberate use of controlled violence to impose costs while avoiding conventional escalation. This method combines physical force, legal ambiguity, psychological pressure, and diplomatic engagement. India’s future preparedness must therefore account for non-linear escalation ladders. Traditional binary distinctions between peace and war are insufficient. Training, force posture, and political decision-making must anticipate grey-zone tactics that blur these boundaries.

The Galwan Valley clash was not merely a tactical episode but a strategic shock that exposed deep structural flaws in India-China border management and compelled a reassessment of long-held assumptions. The lessons derived from Galwan extend beyond eastern Ladakh and have enduring relevance for India’s military posture, diplomatic engagement, and strategic planning

Tactical Superiority Cannot Compensate for Strategic Ambiguity. At the tactical level, Indian troops displayed resilience, discipline, and courage. However, Galwan highlighted the risks of operating under ambiguous strategic assumptions — particularly the belief that restraint would be reciprocated. Clear political guidance, explicit red lines, and delegated authority are essential to ensure that tactical actions align with strategic intent. Ambiguity at the strategic level creates vulnerabilities on the ground, especially against an adversary willing to exploit uncertainty. If the situation had been correctly analysed by the Indian leadership, the loss of lives of our soldiers could have been avoided.

Theatre-Level Integration Is No Longer Optional. The 2020 crisis underscored the importance of jointness and theatre-level coordination. The PLA’s ability to mobilise across multiple sectors simultaneously reflected a high degree of centralised planning and integration. For India, effective deterrence along the LAC requires seamless coordination between land, air, space, cyber, and intelligence domains. Accelerated progress towards integrated theatre commands, enhanced ISR capabilities, and faster civil-military decision loops are critical.

Political Resolve Is a Core Component of Deterrence. One of the most consequential outcomes of Galwan was India’s political response. By linking border stability with the overall bilateral relationship, New Delhi signalled a willingness to bear economic and diplomatic costs to defend territorial interests. This political clarity strengthened military deterrence and reduced incentives for further Chinese adventurism. Galwan reaffirmed that deterrence is as much political as it is military, and that sustained resolve shapes adversary calculations over time.

India-China Competition Has Become Structural. Perhaps the most enduring lesson is that India-China tensions are no longer episodic or manageable through crisis diplomacy alone. The rivalry is now structural, driven by competing strategic visions, regional ambitions, and power trajectories. This implies that future crises are not anomalies but features of the relationship. Policy planning must therefore move from crisis avoidance to crisis management and long-term competition, with clear-eyed assessments of costs, risks, and trade-offs.

The most enduring lesson is that India-China tension is no longer manageable through crisis diplomacy alone. The rivalry is structural, driven by competing regional ambitions. This implies that future crises are not anomalies but features of the relationship. Policy planning must, therefore, shift from crisis avoidance to crisis management, with clear identification of risks and trade-offs

Conclusion

The Galwan clash of 2020 marked a watershed in India-China relations. It ended the assumption that peace along the LAC could be indefinitely preserved through protocols and dialogue alone. At the core of the crisis lay Daulat Beg Oldie — a strategic pivot where infrastructure, geography, and power intersect.

Galwan did not resolve the boundary dispute; it clarified its nature. The LAC is now a hardened frontier, and stability will depend less on confidence-building measures and more on sustained deterrence and strategic clarity.

-The author retired as Major General, Army Ordnance Corps, Central Command, after 37 years of service. A management doctorate and expert on defence modernisation, he is the author of four books, including the Amazon bestseller “Breaking the Chinese Myth,” and a frequent media commentator. He is affiliated with several leading defence and strategic studies institutions in New Delhi. The views expressed are of the writer and do not necessarily reflect the views of Raksha Anirveda