The bilateral and particularly the defence ties between India and Europe are two dimensional. Firstly, India must maintain relations with European Union, representing 28 countries, and secondly bilaterally with bigger EU members and non-EU members, separately.

India pragmatically has developed strategic and defence partnerships with UK, Italy, Germany, Spain, and Sweden. Some analysts believe that the absence of a formal EU institutional framework is hampering development of EU-India military collaboration. They propose including India in the European Defence Fund and establishing a formal bilateral military partnership.

Meanwhile, India has focused on developing relations with both EU and non-EU countries. In this regard, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit in mid-June to Cyprus and Croatia, both members of the EU, preceded by External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar’s visit to France, EU, and Belgium earlier in June and to the Netherlands, Denmark, and Germany earlier in May 2025, demonstrate this willingness.

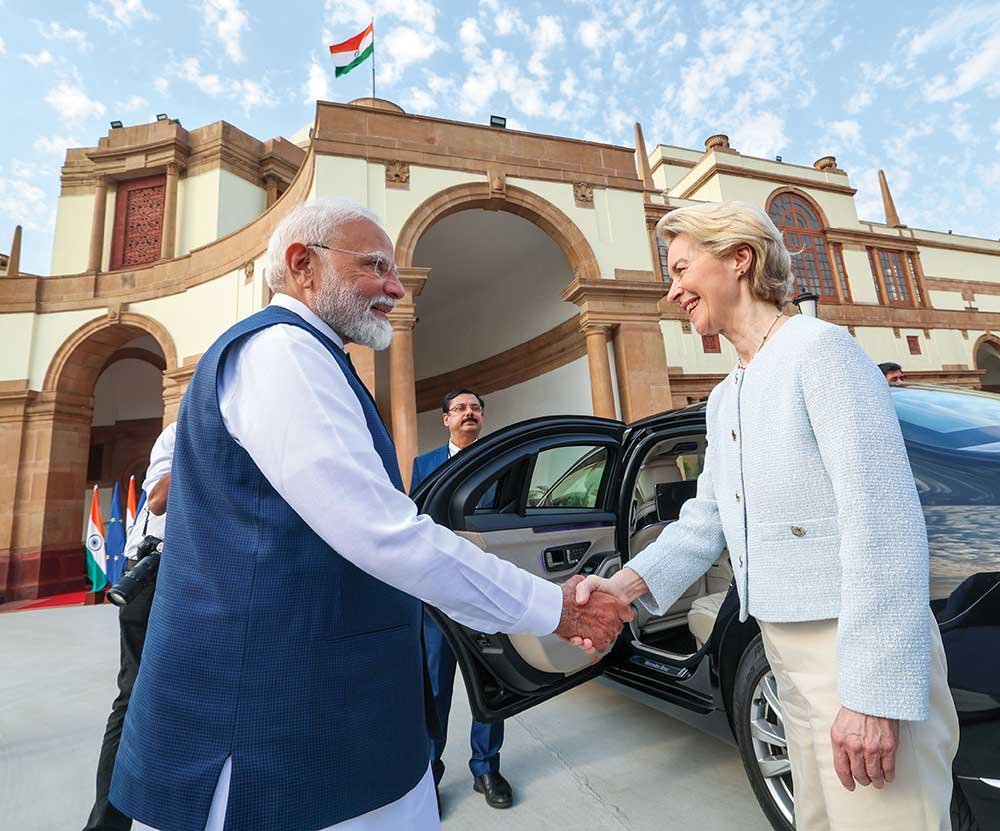

As a result, bilateral relations are rapidly evolving, anchored in the India-EU strategic partnership. In February 2025, during the visit of Ursula von der Leyen, president of the European Commission, and the EU College of Commissioners to India, the two sides had welcomed growing defence cooperation, including joint exercises and collaboration between the Indian Navy and EU maritime security entities.

The two sides have also committed to exploring a security and defence partnership. In this context, one must closely examine the opportunities for deepening the partnership provided by the Joint White Paper (JWP) on European Defence — Readiness 2030, issued by the European Commission in March 2025.

Indian and European Security Challenges

Both Europe and India currently face many challenges to their security. A triad of challenges has pinned Europe in a corner – due to the changing US foreign policy, the continuing conflict in Ukraine, Gaza and Iran and pessimism about a post-war European peace. Similarly, emerging from the latest conflict with Pakistan, New Delhi’s strategic imperative to diversify its partnerships and enhance its defence capacity is now more urgent than ever, given the collusive threat posed by the China-Pakistan nexus.

Naturally, a powerful consensus is emerging: the long-nascent India-EU relationship must urgently acquire a security and defence dimension. The opportunities are significant, but they must be pursued with a clear-eyed understanding of the challenges and based on realistic expectations.

As European nations seek to expand and modernise their defence industry to meet emerging and future threats, India can play a crucial role in the EU’s defence industry supply chains. The EU and India are exploring the possibility of a defence and security pact, also called the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO), akin to the EU’s agreements and pacts with Japan and South Korea.

The PESCO framework would enable the EU member states to work jointly with India to develop and invest in shared defence capabilities and improve the operational readiness of the armed forces. While this will help India gain access to advanced technologies, European states would benefit from the robust and competitive manufacturing facilities of India, provided these manufacturers set up factories in India.

Opportunities for Indian Defence Sector

India can capitalise on the EU’s allocation of 500 billion Euros to ramp up its ammunition stocks. Indian ordnance factories manufacturing ammunition shells have the idle capacity to cater for surge requirements during the war and have modernised manufacturing to make hi-tech ammunition, which can be used to equip EU militaries.

India pragmatically has developed strategic and defence partnerships with UK, Italy, Germany, Spain, and Sweden. Some analysts believe that the absence of a formal EU institutional framework is hampering development of EU-India military collaboration. Meanwhile, India has focused on developing relations with both EU and non-EU countries

Some EU members have already ordered ammunition from these Indian entities. Joint production with private ammunition manufacturers also remains a possibility, as some of these manufacturers already have collaborations with EU companies.

The Indian government is attempting to kick-start India as a leading shipbuilder with a multi-billion-dollar cash injection, in line with its Viksit Bharat 2047 vision. The government plans, propose to incorporate the state-owned shipyards to provide the much-needed functional and financial autonomy that is presently unavailable to them due to the bloated bureaucracy in the Ministry of Defence.

In its most recent budget announced on 1 February 2025, the government allocated US$ 28 billion for a Maritime Development Fund (MDF) to support the country’s maritime sector. This would help India emerge as a globally competitive shipbuilding hub.

European Presence in India

Dassault India is in the process of establishing a Maintenance, Repair, Overhaul (MRO) setup near Jewar International Airport in Greater Noida, U.P., which can be scaled to provide maintenance support to combat jets from EU states. It already has a joint facility with Reliance near Nagpur for manufacturing aircraft parts.

Safran has an MRO facility in Hyderabad for aero-engines. The Tata group, in collaboration with Airbus, has already begun manufacturing C295 military transport aircraft at its factory in Vadodara, Gujarat. These facilities can be scaled up to meet Rafale requirements for EU members.

The Indian Offer

India possesses a robust engineering talent pool, established defence production infrastructure, a large defence budget with a focus on research and development, and indigenisation, allowing it to produce complex military equipment domestically, and potentially export to other countries as well.

Government policies can encourage domestic and foreign private players through Foreign Direct Investments (FDIs) and other incentives. Further, the sector is also capable of absorbing foreign technology for ‘Make in India’ initiative.

However, the bigger prize would be a Security of Information Agreement (SIA), a key pillar that currently constrains the exchange of classified or sensitive information between the EU and a third country, such as India. An SIA would help unlock more sensitive areas of cooperation, including Indian participation in Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) projects, the EU’s framework for joint defence capability development.

In the immediate term, the potential for cooperation is not just abstract; it is about addressing acute supply chain vulnerabilities and seizing a historic economic opportunity. The war in Ukraine has exposed deep frailties, driving up prices of defence materials. 155mm artillery shells, something that India’s defence industry is now exporting widely, are just one example of an immediate opportunity.

However, an important yet persistent hurdle, which is likely to remain, is the India-NATO relationship. While NATO does not expect a formal partnership with India, there are expectations of India considering becoming a “contact country,” an informal, flexible arrangement that requires no binding treaty

India-NATO Relationship

However, an important yet persistent hurdle, which is likely to remain, is the India-NATO relationship. While NATO does not expect a formal partnership with India, there are expectations of India considering becoming a “contact country,” an informal, flexible arrangement that requires no binding treaty. Such status would open the door for Indian officers to attend courses at the prestigious NATO Defence College in Rome and for Indian observers to participate in select exercises, such as those in the Baltics.

In the wake of the high-level visits this year, India should endeavour to explore sales of Advanced Towed Artillery Guns (ATAGs), the Pinaka Multi-Barrel Rocket Launcher, air defence missiles, and radars that meet NATO standards. India should tap this window of opportunity with the assistance of Israel and South Korea. Both these nations have robust defence partnerships with India.

Similarly, Europe needs reliable partners for everything from drone motors and propulsion systems to explosives, such as ammonium nitrate, and the rare earth elements that are the foundation of modern military hardware.

Beyond traditional defence, cooperation in the space domain offers immediate dividends. The EU’s Copernicus programme, an Earth observation system with growing security applications, is a prime example. The legal text governing third-party cooperation with Copernicus makes no distinction between India and a close partner like Norway, presenting a clear pathway.

The focus on space situational awareness is critical for both sides. By leveraging the Copernicus model, where financing for infrastructure in third countries can yield a return in data and services, India can integrate into a cutting-edge civilian-military programme, strengthening its capacities while contributing to a shared vision of space security and sustainability.

European Stimulus

Notwithstanding these challenges, the enormity of this moment in Europe’s history is unmistakable. True to the EU’s nature as an economic regulator, its ReArm Europe plan is an economic instrument that promises member states fiscal flexibility to generate an estimated €650 billion in additional defence spending over four years, which would not count towards national deficit limits.

This is complemented by a proposed €150 billion loan instrument, the ‘Security Action for Europe’ (SAFE), to further support joint investment. This massive injection of capital creates an unprecedented market for India’s burgeoning defence sector to meet its export goals. For India, this is an opportunity to integrate into resilient supply chains and co-develop critical technologies.

The Way Forward

Ultimately, consolidating a bilateral geopolitical outlook and building this partnership is about more than just military hardware; it is about preserving the rules-based international system and jointly shaping the standards for the technologies that will define this century.

The path forward is not without its challenges, which require frank acknowledgement. From a European perspective, there is a persistent lack of understanding of the Indian administrative landscape—a confusion about who holds the authority to make decisions and drive concrete projects.

Conversely, India is often a “victim of its own success,” with several powerful EU member states preferring the expediency of bilateral defence ties over a slower, more complex EU-level relationship. These hurdles are compounded by a stark mismatch in diplomatic capacity. The absence of a dedicated Defence Attaché at the Indian embassy in Brussels is a glaring gap that needs to be corrected.

Once such minor irritants are taken care of, the India-Europe defence partnership can blossom into a win-win situation for both.

-The writer is a New Delhi-based senior commentator on international and strategic affairs, environmental issues, an interfaith practitioner, and a media consultant. The views expressed are personal and do not necessarily carry the views of Raksha Anirveda