Air Chief Marshal Rakesh Bhadauria’s statement that the advanced medium combat aircraft (AMCA) has been given the go-ahead and that no imports of fifth generation fighter aircraft are planned indicates that India’s stealth fighter is back on the drawing board. According to IAF sources, the AMCA prototype should roll out of the hanger by 2024-2025, with the first test flight taking place approximately two years after that and serial production starting in 2029.

Acquiring stealth capability assumes significance in the backdrop of the rapid expansion of the Chinese PLA Air Force, which already has two concurrent fifth generation fighter programmes, of which the J-20 is close to entering full scale production and the J-31 is being developed for export to countries such as Pakistan. China is also reportedly developing a naval stealth jet which will have vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) capabilities for carrier operations. And by the early 2030s, the PLA Air Force could well be test flying a sixth generation fighter.

Stealth aircraft are no longer a luxury. The IAF requires low observable fighters to achieve air dominance in the heavily fortified air defence environments in India’s neighbourhood. Extended combat range, long-range standoff weapons, smart engines, stealth/low observation features and sensor fusion capabilities are needed to counter airborne and surface-based air defence systems that are being fielded by India’s adversaries. Precision attacks on high-value targets require stealth aircraft capable of sustained flight at high speeds and armed with standoff long-range weapons.

Starting fresh

India’s original Plan A was a joint venture with Sukhoi which was developing the Su-57 stealth fighter. However, nearly a decade of unsatisfactory progress, the IAF walked out of the project in 2018 citing critical shortfalls in the Russian aircraft. These included:

Stealth: The IAF said the Su-57 was badly engineered to be stealthy at all. It wanted an aircraft like the American F-35 or F-22 with a tiny radar cross section, but the Russian jet was a compromise between stealth and super-manoeuvrability, which is characteristic of Sukhoi fighters.

Engine: The Su-57’s engines were unreliable, the IAF said.

Supercruise: The Russian jet lacked super cruise – the ability to travel at supersonic speeds for extended flights without engaging fuel guzzling afterburners.

Radar: The Indian side wanted long-range radar which the Su-57 lacked. The F-35, for instance, reportedly has a 900-km detection range.

Data links: The Russian jet wasn’t fully ready for networked warfare or the ability to share data with other battlefield assets.

With the IAF now having decided to take the route of indigenous stealth aircraft development, there’s a lot of new technologies India will have to reinvent at home. Information on the AMCA is limited which is expected considering the nascent state of the programme.

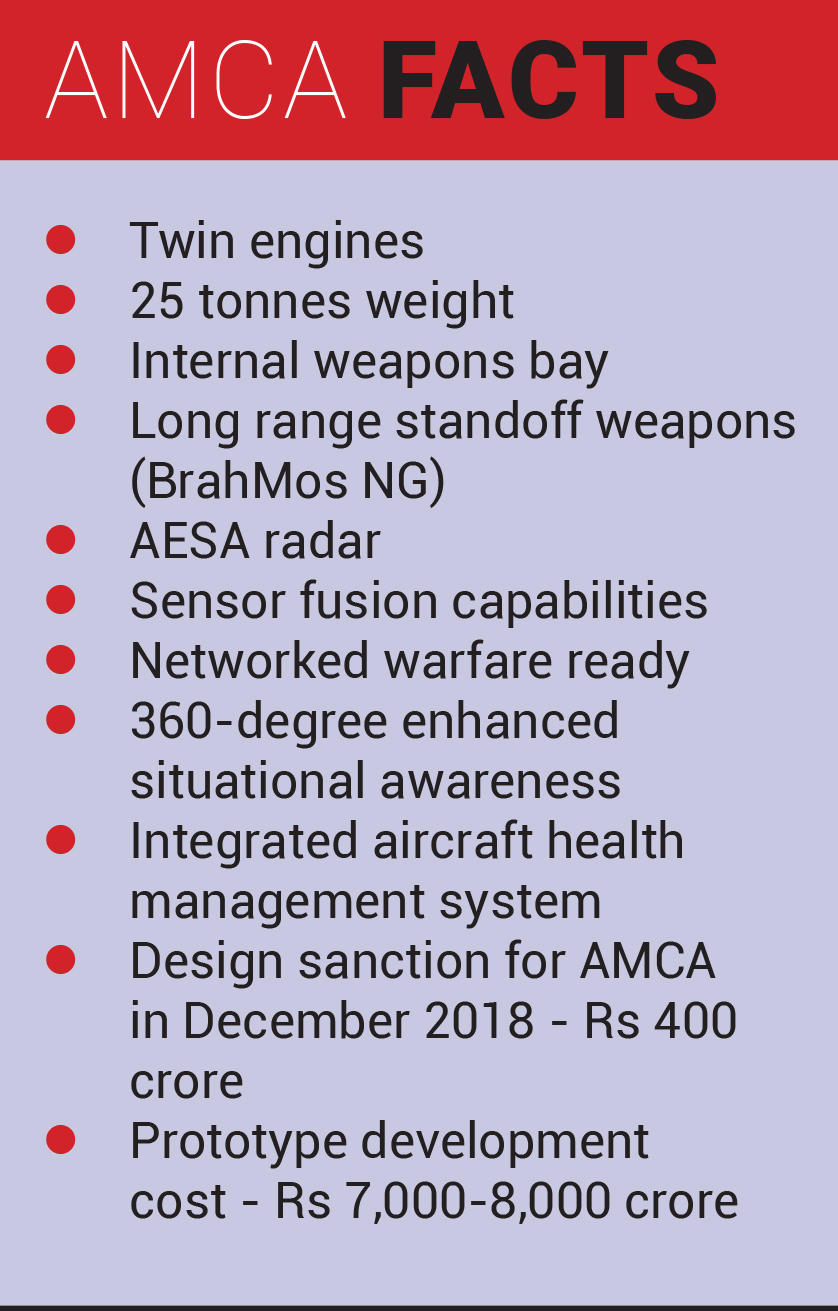

Officially, the DRDO says the aircraft will have a bunch of fifth generation capabilities such as net-centric warfare, vehicle management (including weapons), data fusion, decision aids, integrated modular avionics, internal carriage of weapons, signature control with sharpening for low observability, AESA radar, infrared search-and-track, supersonic persistence, high-speed weapon release and thrust vectoring. Plus, the aircraft would be able to “swing roles” variously between long/short-range and air-to-air/ground strike. In October 2019, Air Marshal Raghunath Nambiar, the chief of the IAF’s Western Air Command, agreed these fifth generation technologies would be the basic tenets of the AMCA.

According to Vladimir Karnozov of Aviation International News, the AMCA is likely to be an “electronically” actuated airplane rather than hydraulically operated. Instead of the digital flight-control computer as used on the Tejas, the AMCA is to have a distributed processing system employing fast processors and smart subsystems that can pass over and combine the processing power available in them.

The new airplane is also planned to have a central computational system connected internally and externally on an optic-fibre channel by means of a multiport connectivity switching modules. Also mentioned is fly-by-light, electro-optic architecture with fibre-optic links for signal and data communications.

Lessons from the LCA

The LCA programme, which led to the successful indigenous Tejas fighter, offers five key guidelines for the AMCA’s developers:

- Developing an aircraft from scratch is not easy. With India’s aeronautical industry stuck in licensed production mode for decades, lack of innovation and a low technology base plagued the project.

- Timeframes and deadlines become meaningless. Delays were expected but once Western sanctions kicked in, the project took over 30 years to yield results.

- Costs can balloon way beyond expectations. Defence projects are a money pit. Even the US, with all its technological might, has struggled with the F-35, with the entire development-to-procurement cycle costing over $1 trillion.

- Lobbies can work to sabotage the project. Until the Narendra Modi government came to power, the Tejas seemed like flying into the sunset as reports of its weaknesses started appearing in the media. The AMCA will face similar media trials.

- Persistence pays. The fact that the Modi government rammed the aircraft through to serial production shows that every major weapons platform needs a mentor. Similarly, the highly successful BrahMos had solid backing from the then Prime Minister PV Narasimha Rao. The AMCA will need someone powerful to ensure it gets timely funding and top scientific talent from India’s defence design and production establishments until it is ready to take off.

Riding the LCA wave

Successful projects create thriving industrial ecosystems. Like the BrahMos, the LCA project has led to a huge aerospace base in the country. It has created indigenous design expertise, design tools and test facilities. It has allowed the Aeronautical Development Agency (ADA), which designed the Tejas, to gain expertise in the processes of flight testing and certification and in prototype development. According to the Agency, as many as 149 work centres in 28 cities across the country have contributed to the LCA programme. These centres are now available for the AMCA project.

If large orders for the AMCA are assured, private Indian companies will also jump in setting up new facilities across the country. The AMCA could follow the BrahMos model of private partnership to ensure accountability and freedom from sabotage.

Ideal stealth fighter

The IAF did well by stepping away from the semi-stealthy Su-57. Stealth is not the magic cloak of invisibility. Its effectiveness is degraded by a variety of factors – such as externally mounted weapons, opening of internal weapons bay and heat emitted from engine exhausts. Plus, if aircraft do not stay out of range, they will be detected and identified. Radiation emitted by sensors used by the aircraft will compromise stealth, and so will communications to and from the aircraft.

This is why the US Air Force conducts stealth missions mostly at night and in sanitised airspace with near zero chances of being targeted. But even then a F-117 Nighthawk was shot down by well trained Serbian air defence crew using an outdated – albeit effective – Russian made surface to air missile.

The IAF should factor in all these aspects before the AMCA reaches the prototype stage. The good news is that in contrast to the LCA project – which was treated like a poor cousin – the IAF is working closely with the ADA in finalising the AMCA’s configuration, and is deputing fighter pilots to provide valuable inputs to ADA designers.

New strategies for the future

In 2012 when India entered into a partnership with the Russians, the IAF declared it could acquire as many as 144 fifth generation fighters. In hindsight, acquiring such a large number of stealth planes – that are not only costly to buy but also super expensive to maintain – was not possible for India.

Neither was such a large purchase unnecessary. When stealth aircraft were the rage in the early 2000s, military experts and air force commanders were of the view that stealth jets would replace all other types of aircraft in the near future. However, this hasn’t happened primarily because of the high costs of development and maintenance.

The huge expense of developing, buying and maintaining stealth jets means they will – at least in the next couple of decades – be used sparingly, perhaps at night and escorted by plenty of non-stealth aircraft. This scenario has completely upended predictions that stealth fighters would play a dominant role in air combat by the early part of the 21st century.

In this backdrop, the IAF will have to formulate new strategies while inducting fifth generation fighters and prepare for stealth centric warfare in the distant future. Stealth fighter-bombers are optimal for precision strikes on high value targets located deep within heavily defended areas. In the air superiority role, airspace dominance by eliminating enemy fighters and AWACS from well beyond visual ranges would be another key role.

Success begets success

On October 11 this year, two days after Defence Minister Rajnath Singh visited the engine manufacturing facility of Safran at Villaroche near Paris, the French company announced it was interested in co-developing aero-engines for the AMCA. It also proposed to develop and produce the engine totally under the “Made in India” initiative that would be customised to the aircraft’s needs.

“Safran, supported by French authorities, is the sole company in the world to propose a complete transfer of know-how and know-why, allowing India to be fully autonomous in the future,” the company said, adding that India is the sole country in the world to whom such a transfer has been proposed.

Safran’s offer is an indication that the highly rated French company is aware of India’s determination to develop a world class stealth fighter, and is therefore keen to work with a promising programme.

Meanwhile, unlike the original 144-aircraft acquisition plan, the IAF’s current plan is more realistic. In view of the complexities involved in developing super cruise capable engines, the service has decided to go in for two squadrons of AMCA Mark-I with a General Electric-414 after burning turbofan engine. The next five to six squadrons of AMCA Mark-II (expected in 2035) will have a more powerful engine.

In the space of a decade, India’s stealth fighter programme has moved from being overly ambitious to cautiously optimistic. More than anything, it indicates that the AMCA is in good hands.

-The author is a New Zealand based defence analyst. His work has been quoted extensively by leading think tanks, universities and publications worldwide.